Back to selection

Back to selection

NYFF Critic’s Notebook: The Velvet Underground and The Girl and the Spider

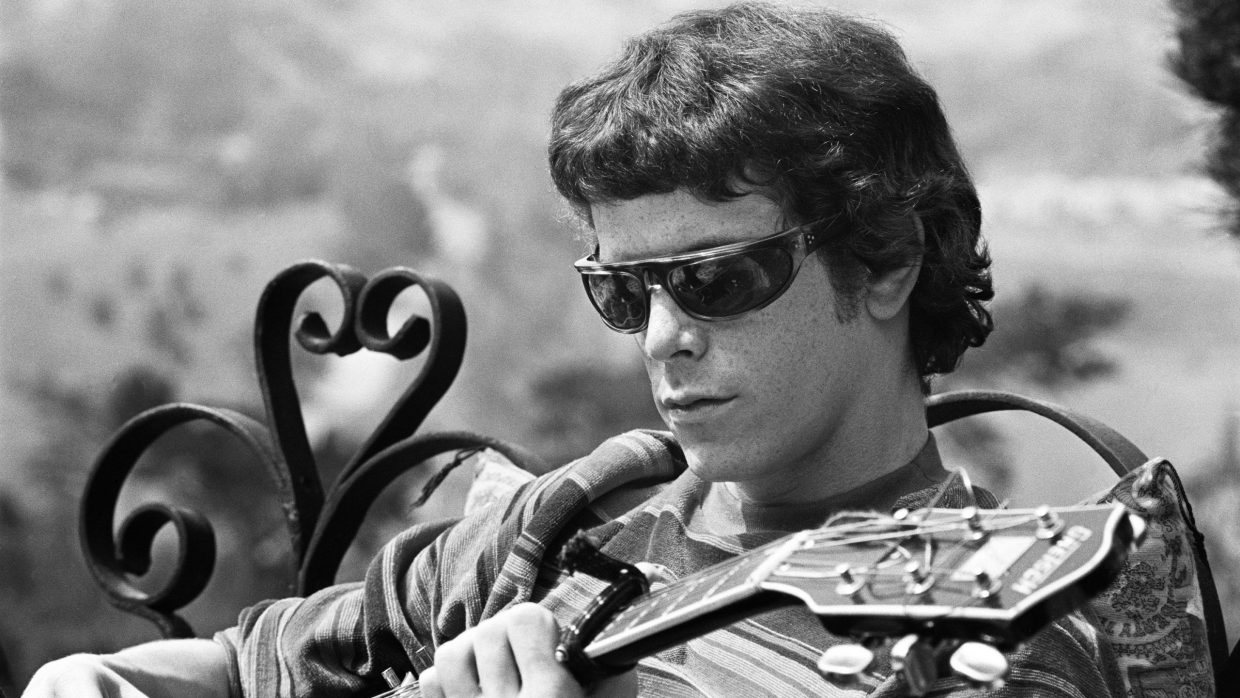

Lou Reed in The Velvet Underground (Photo: Apple TV+)

Lou Reed in The Velvet Underground (Photo: Apple TV+) Peter Buck, the guitarist for R.E.M., is often quoted as saying, “The first Velvet Underground album only sold 10,000 copies, but everyone who bought one formed a band.” Now it seems, all those bands are the subjects of documentaries. Finally, even the Velvet Underground. The eponymous film is one that Todd Haynes appeared destined to make. Popular music, rock’n’roll mythology and the vagaries of self-invented personas are a core of the director’s filmography, going back to the Super-8 transgression of Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story, a melodramatic biopic of the ‘70s pop singer cast with Barbie dolls. Velvet Goldmine (1998) reframed glam-rock legend as a cross between Ziggy Stardust and Citizen Kane, and I’m Not There (2007) absorbed Bob Dylan’s shape-shifting strategies into its own form, with an array of actors incarnating the songwriter in his various mercurial guises.

Given Haynes’s bold ideas about turning pop narratives inside-out, the surprising thing about The Velvet Underground is how straightforward it is. There’s nothing “meta” about its structure, which offers a precisely curated time capsule data dump of sorts, a bit like what you’d see in a science-fiction film where the alien taps into a flickering visual archive of mankind’s recorded history to better grok life on this strange blue planet. In this case, we’re the aliens, and the planet is 1960s New York City, where a drug-sex-noise-art-poetry freak-out is erupting out of the bohemian haunts into the popular media. Out of this “exploding plastic inevitable,” to use Andy Warhol’s lingo, came the Velvet Underground, the elemental New York rock band founded in 1964 by Lou Reed, John Cale, Sterling Morrison and Angus MacLise (with Moe Tucker to replace him on drums a year later). It’s common knowledge that precious little performance footage of the band exists, although a few stray bits do – in Warhol films, and of the band’s residency at the Dom (and Electric Circus), a former Polish social club on St. Mark’s Place (now a complex boasting loft apartments, let us weep). With that obstruction comes the realization that the film isn’t as conventional as it might seem. And so, Haynes adds another obstacle: No talking head or archived interview is allowed unless the subject is able to offer a first-hand account of the band or one its members, primarily Reed, who died in 2013, four years before Haynes signed on to direct the film. No Bono allowed! (Reed’s interviews are presented archivally, while Cale and Tucker, the sole surviving bandmates from the classic lineup, appear throughout).

The documentary, which played at the recent New York Film Festival, now screens at Film Forum, and bows Oct. 15 on Apple TV+, thus has a different vibe than the usual rock-doc. Haynes is so invested in the deeper cultural context that it’s a full hour of prehistory before the band even comes into being. We’re first introduced to avant-garde violist John Cale, a young Welshman on a mission, and his appearance on the TV game show What’s My Line? (The celebrity panel is treated to a brief performance of Erik Satie’s “Vexations,” which Cale had played for 18 consecutive hours). And, boom, into the dizzying whirl of LaMonte Young, Tony Conrad and that peculiarly dirty brand of New York minimalism, flaming creature Jack Smith, Delmore Schwartz, underground cinema, and the whole nuclear subcultural thrum. Reed’s entry to the music business comes from the other side of the spectrum. By day, he concocts bubble gum and surf-rock hits for the discount record company Pickwick – which precursed the VU in the unlikely form of fake garage stomp band The Primitives, with Cale, Conrad and MacLise raving through the dance-craze novelty stomper “The Ostrich.” Reed’s boss at the label recalls his frequent tardiness, and trips to the emergency room, due one presumes to the harsh afterburn of his drug use. His next boss, Andy Warhol, would prove even more indulgent, fostering no less than one of the greatest rock’n’roll recordings of all time: The Velvet Underground & Nico. Famous for Warhol’s peelable banana cover art, and radically anti-Summer-of-Love anthems as Reed’s harrowing, transcendent “Heroin” and the raw, droning throb of Cale’s viola on “Black Angel’s Death Song,” the album also cast an ethereal spell with the appearances of the German chanteuse Nico (“All Tomorrow’s Parties,” “I’ll Be Your Mirror”).

Haynes uses a split screen throughout – inspired by Warhol’s use of two projectors in screenings of Chelsea Girls – often running a contemporary interview on the right while relevant archival clips play on the left. It makes for a considerably denser conveyance of information, and is exceptionally useful during the contemporary interviews with former Warhol superstars like Mary Woronov (shown in one of her legendary “whip dance” performances at a VU gig), and contemporaries like Jonas Mekas, who recalls how he suggested the Empire State Building as a subject for Warhol’s camera, while a clip from Empire runs on the left side of the screen. Of all the interviewees, it’s Velvets superfan Jonathan Richman who steals the movie. He was a regular at the band’s dozens of Boston Tea Party shows and the founder of the first and best of those groups formed after hearing their first album, The Modern Lovers. Richman, a sweet, freaky kid at the time, recalls that the first time he saw the band, he knew “these people would understand me.” And leave it to Conrad, minimalism’s rebel angel, Cale’s former roommate at the notorious 56 Ludlow Street compound and the guy who owned that copy of the sleazy paperback that gave the band its name, to put it all in a nutshell. “Pop culture dissolved high art, melting crystalline structures,” he says, in an archival voice-over. “Which was just what we had in mind.”

In the past couple of months, I’ve dutifully been screening submissions for a couple of festivals (including one I co-direct in Tallahassee, Fla.), a task that can grind at your patience sometimes. I was struck by a wave-let of little films that consisted of what I’d call “white people sitting in rooms talking,” which, while the term broadly describes masterpieces by John Cassavetes and Eric Rohmer, not to mention most of the nouvelle vague and, for better or worse, mumblecore and its aftermath, it can also suggest a kind of laziness — minimalism as a crutch to wobble past problems of budget, location or imagination. Like, you’ve got a camera, don’t you want to make a movie? The Girl and the Spider, from the Swiss brothers Ramon and Silvan Zürcher, likewise features a whole bunch of white people hanging out inside various apartments talking … but not really saying very much. And it’s totally cinema. Ramon, who previously mapped the quirks and mysteries of interior space in The Strange Little Cat (with twin bro Silvan producing) this time has a literal spider hanging out, a big hairy one, observing some half-cryptic human theater arising over a couple of days as a young woman named Lisa (Liliane Amuat) moves out of a multi-roommate apartment into her own place. However, the camera mostly pivots around and from the point-of-view of Mara (Henriette Confurius), Lisa’s apparent former lover, unsettled by her departure from under their sharted roof. There’s a full ensemble of characters, milling around, flirting with and misreading each other and sometimes introduced so casually that it takes time to sort out their place in the story. Indeed, it takes time to sort out what even the story is, a puzzle of whisper-subtle intrigue and innuendo that involves a promiscuous social circle that spirals out of the hive activity in Lisa’s about-to-be former flat. The Zürchers animate what could be a dry, theatrical exercise with an appealing cast whose half-finished sentences work like Thelonious Monk piano lines, making elliptical pauses vibrate, and framing faces so that the movement of eyeballs can become a ballet. They also relish (apparent) natural light, framing scenes like coffee-table art book photography, with discrete captures of individual domestic objects thrown in like pages in some ironic catalog. The insistence on keeping the cast largely confined to a mise-en-scene of doorways and windows, never suggests anything allegorical (as it might in Bunuel) or veers into baroque melodrama (as it might in Fassbinder), but creates instead a space intimate enough for the film’s vaguely tongue-in-cheek vibes to resonate, a precise, austere setting where even a character’s herpes sore can become a running gag.