Back to selection

Back to selection

HAWAII AWARD WINNERS AND A STANDOUT WORK

The Hawaii International Film Festival fittingly wrapped up its 31st edition last week with Alexander Payne’s Hawaii-set-and-shot comedy/drama The Descendants, with a gracious Payne in town for the screening (no George Clooney, alas, though a life-sized Clooney cardboard cut-out was certainly a massive hit in the lobby). “Wine always tastes the best in the region it was grown and made,” noted Payne to an appreciative audience. “I hope that this film plays best in Hawaii.”

The Hawaii International Film Festival fittingly wrapped up its 31st edition last week with Alexander Payne’s Hawaii-set-and-shot comedy/drama The Descendants, with a gracious Payne in town for the screening (no George Clooney, alas, though a life-sized Clooney cardboard cut-out was certainly a massive hit in the lobby). “Wine always tastes the best in the region it was grown and made,” noted Payne to an appreciative audience. “I hope that this film plays best in Hawaii.”

Judging from audience response, Payne got his wish; the film (to be released nationally November 15) won the festival’s Audience Award for Narrative Feature, with many viewers praising its respectful take on author Kaui Hart Hemming’s source novel, as well as its catchy all-Hawaiian soundtrack. Taking the Audience Award for Documentary Feature was Aloha Buddha, Bill Ferehawk and Dylan Robertson’s fascinating look at the complicated history and unique present of Japanese Buddhism in Hawaii, while the Audience Award for Best Short went to Mitsuyo Miyazaki’s slick Tsuyako, involving a love affair between two women in post-war Japan.

Earlier that week, in the restored 19th-century glamour of the Hawaii’s Governor’s Mansion, festival staff, guests, and press gathered for the announcement of the jury awards. Prashant Bhargava’s Patang (The Kite), a tale of family secrets revealed and denied during the extraordinary kite festival of Ahmedabad, India, took the “Halekulani Golden Orchid Award” for Narrative Feature; its vibrant Super-8 footage of the festival and its organic feel for the city itself turned what could have been a familiar melodrama into a rich exploration of place and spectacle.

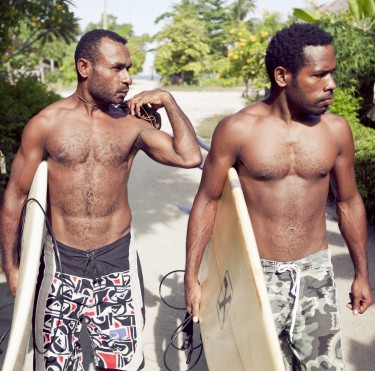

Earning the award for Documentary Feature was Adam Pesce’s Splinters (pictured above), deceptively clad as a surfing film about the sport’s rise in Papua New Guineau but more pointedly an engrossing, endlessly surprising examination of social hierarchies, clan rivalries, and economic and cultural change within the region. In recent years a wave of sports films set in unusual locations have appeared at festivals—Skateistan, about skaters in Kabul, for instance, or God Went Surfing With the Devil, about Palestinian surfers—but Splinters stands out for its focus not on those bringing the sport from one culture to another, but on the culture learning to accept the sport. The film follows several PNG surfers from the village of Vanimo as they prepare for an upcoming contest; like any good sports doc, Splinters offers up fast-talking showboaters, unassuming talents, underdogs, villains, and sudden plot twists, along with the prerequisite shots of breaking waves, skillful surfers, and sun-kissed beaches. What makes Splinters a great sports doc—and a great documentary in general—is its focus on the social structure that supports (or destroys) the surfers, and on the rapid cultural upheaval that surrounds them.

Concluding the awards was Ruslan Pak’s South Korean/Uzbekistan crime thriller Hanaan, which won the Network for the Promotion of Asian Cinema (NETPAC) Award. Following a Korean/Uzbeki cop as he goes undercover to bust a drug gang, the film channels a Wire-like intimacy into an even grungier, unknown realm, and earned praise from the NETPAC jury for “culturally bridging social issues with strong artistic integrity accompanied by outstanding performances.”