Video on Demand — February 2013

Video pick of the month

Video pick of the month

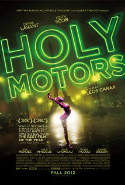

Holy Motors

“The social web can’t exist until you are your real self online,” said Sheryl Sandberg on Charlie Rose last year. “I have to be ‘me’, and you have to be ‘Charlie Rose,’” the Facebook COO told the talk show host.

“It’s me” — that single line appearing late in Leos Carax’s Holy Motors unexpectedly devastated me at the film’s Cannes premiere, and perhaps its memory is what’s causing me to recall Sandberg’s statement, which is certainly in line with similar comments by her boss, Mark Zuckerberg. In an age in which online platforms offer the possibility for anyone to craft for themselves a variety of personas, Zuckerberg paradoxically argues that we will move towards a single “true self,” one that finds its fullest representation through social media sharing.

Whether or not you agree with Zuckerberg, it’s hard to disagree that one of the great pleasures of cinema as a popular entertainment — its ability to transport the viewer into the skin of someone else — is now just as readily found for new audiences through gaming and online interaction. Whereas the style, attitudes and often ideologies of cinematic heros — and sometimes villains — would rub off on viewers, shaping their thoughts, behaviors, and dreams, now people can just as easily create a succession of alternate personas for themselves, sharing each one only to the small audience it’s specifically created for. Zuckerberg may believe that over time these personas will all congeal into that “true self,” but he has to — his business depends on it. However, the ability to shapeshift, “present,” and match online identities to one’s specific roles in life may be a power that, now unlocked, is simply too powerful to suppress.

Holy Motors — Carax’s fifth feature, and his first since 1999’s Pola X — isn’t directly about what I’ve just written above, but it is one of the film’s great strengths that its rambunctious, episodic narrative encapsulates these ideas as well as a whole host of others. The film begins with Carax himself awakening in a hotel room. He opens a door and wall and enters… a theater, where an audience awaits to be entertained. Throughout the film, references to cinema — early motion studies by Etienne Jules-Mary and Edward Muybridge; direct references to King Vidor and Georges Franju; a concluding moment straight out of Pixar — abound. We meet our protagonist, “Mister Oscar” (the remarkable Denis Lavant), who journeys across Paris in a white stretch limo, donning disguise after disguise to become a beggar, a beast, a hitman, a concerned father, an ex-lover. The stories that result hopscotch through various genres, forming a history of not just 20th-century cinematic storytelling but the director’s own personal relationship to it. (Scott Macaulay)