Back to selection

Back to selection

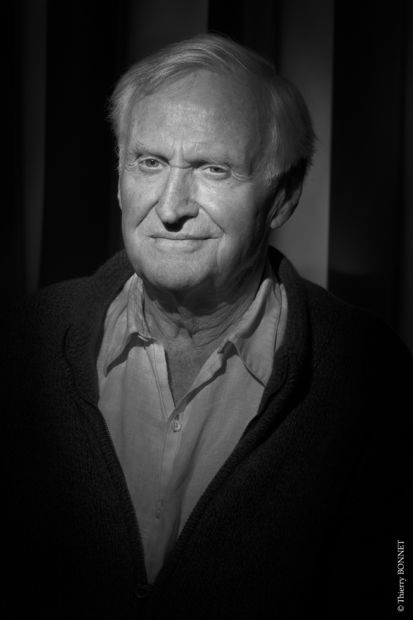

10 Lessons on Filmmaking from Queen and Country Director John Boorman

Queen and Country

Queen and Country English filmmaker John Boorman returned to Cannes this year with Queen and Country, his autobiographical sequel to Hope and Glory. At 81 years old, Boorman claims this is his very last movie, and after such an illustrious career — with films including Point Blank, Deliverance, Excalibur, and The Emerald Forest — he ends on a very high note.

In 1952, young Bill Rohan (Callum Turner) must leave his idyllic countryside home on the River Thames for two years’ Army conscription. Rather than being shipped out to fight the Chinese in the Korean War, Bill is enlisted with his friend Percy (Caleb Landry Jones) to instruct newer recruits in the art of typing and to brief them on what he sees as an unjust war. The two find themselves in a prison-like setting where they must find humor in every situation just to get by. Outside the camp, Bill falls in love with aristocratic Ophelia (Tamsin Egerton), an impossible relationship. Through it all, we see the young future director’s love of film blossom into a passion that drives his life thereafter.

Much like its Oscar-nominated predecessor Hope and Glory, Queen and Country is a delight to watch, full of delicate humor and an uncanny vividness in its recreation of a generation of change. Few directors can bring the viewer so fully into an unfamiliar situation as Boorman.

We sat down with the director in Cannes to find out the secrets behind his long and abundant career.

1. Film has a way of being truer than memory.

Everything in [Queen and Country] is based on characters and incidents that occurred. The relationship between memory and imagination is a very mysterious one. I sometimes feel that imagination is sometimes closer to the truth than the memory. I remember when I was writing the script for Hope and Glory and I showed the script to my mother and my older sister — because they’re featured very strongly in it — they were astonished because things I thought I had invented turned out to have actually occurred. They were shocked how I could have possibly known these things. Perhaps the same thing occurs in this film, that the elements of imagination are probably closer to the truth than the memories.

2. The business of filmmaking requires a great deal of faith.

The difficulty [with Queen and Country] was finding the money. There is an acknowledgment in the credits for a friend of mine who stepped in. He followed me up one day and asked how the picture is going, how is the preparation, and I said: “Well, I think it’s falling apart, the money dropped out.” And the next day he sent me $350,000 and that got us over that.

More than 50% of independent films collapse, either a couple of weeks before starting shooting or a week after starting shooting. It’s a very hazardous business. You know the story of a man who was asked, “How can you become a millionaire making independent films?” And the answer was, “Start as a billionaire.”

3. Have a vision or don’t make the film.

The most important thing is to have some sort of a vision and as David Lynch said, make the films you want to make, and if your taste doesn’t coincide with the audience, then stop making them.

4. Don’t let the actor direct you.

There are a number of moments in the film, which are about the relationship between film and life, and Rashomon. I saw it when it opened in 1952 and it had a tremendous effect on me. Suddenly I’d seen greater possibilities in filmmaking than I had ever imagined possible.

Mifune — well, I had a very fractious relationship with Mifune [during Hell in the Pacific] because he had very much wrong ideas of the film and the character and I had to correct him. I had a Japanese crew and it was a big loss of face for him to be corrected by me, so we fought all the way through the film. And in every scene he would revert to the character as he saw it and I would have to go on and on until I got what I wanted. It was just awful.

Eventually I had an accident on the reef and I had to stop shooting. And this situation with myself and Mifune was so bad that producers came along and thought that they had to replace me. And they went to Mifune and they said, “You’ll be glad to hear that we’re going to replace Boorman.” And Mifune said: “I can’t agree with that.”

We went to a teahouse in Tokyo. We drank a toast and sake and I agreed to do the film with him. He said, “It’s a matter of honor.” And the producers said, “Listen, this is Hollywood. Honor doesn’t come in to it.” But he wouldn’t budge. So when we started shooting again I thought, “We’re going to be pals,” but he was exactly the same.

5. Cinema doesn’t need to be real. It just needs to be alive.

That was a quote from Ingmar Bergman. Someone in my presence asked him what he was going to do when he was shooting a film and he said he wasn’t trying to make it real, but he was always trying to make it alive. That was very significant and important.

It’s always a matter of the elements. There is always one element that would make a scene into cinema and it always comes from somewhere that makes the scene cinematic, rather than just a scene being photographed. And you’re always looking for that moment, both in the writing and in the shooting and in your dealing with the actors.

6. The script is just a guide. Directing happens on set.

In Point Blank with Lee Marvin, there was a series of scenes in which he was confronting people. One scene where he gets into this penthouse, he’s getting to this guy and they’re in bed together, it’s a great scene. He breaks in and pulls the guy out of the bed, and it’s so very difficult. How would he react, this gangster?

We tried to shoot in different ways, and finally I said, “How about you faint? Such a terrifying situation, you pass out, just bang.” And that’s what we did. So it made the scene work. The actor’s reaction was: “I’m a tough guy, I wouldn’t do that.” Yes, but look at the situation, and it made the scene work. That’s an indication, an idea about how you can convert a scene into cinema.

I think that often happens when you come to shoot a scene, you find that there is something, an element missing and you have to find it some way, that one thing that makes the cinema.

7. Digital isn’t the enemy. Just make a good film.

I’ve been shooting digital for some years now. I was very happy to say goodbye to film because I’ve suffered so much in my whole life from scratches and dirt and loosing shots. The color of the film stock was devised to flatten out the skin tones of movie stars and it’s dreadful. Now digitally we can do whatever we want with color. We can get exactly the color we wish.

8. Silent movies will teach you a lot about filmmaking.

When I was 18 in 1951-1952, the national film theaters opened in numbers and they showed all the great silent films. I haunted the place, and I really fell in love with the silent movies, the origins of film. That’s really where I learned the possibilities of films and learned what they could do.

When they were shooting silent films, they had to devise ways of communicating ideas and stories without the use of dialogue. The techniques they developed, many of them disappeared when sound came in, because when sound came in you were stuck with a very big camera which was very difficult to move and it made films much more static. Filmmaking never quite recovered.

9. Give yourself time to write.

The only thing about writing is that you have time, so you’re doing it on your own and you don’t have the pressure of time. But I always like to write in front of a blank wall because I project the scenes onto the imaginary screen and see if they work.

I kept journals since I was 16. I write all the time, and I’ve got stacks and stacks of them. So when it comes to making a film I go back and look at them and I’m always very disappointed about how unspecific they are, but they’re helpful.

You know, for me the writing process is part of the whole shooting process. One or two universities asked me to give them my archive, my scripts, my old scripts. I don’t keep them. The script is like a map for the film. Once I’ve shot the film, the script has no use at all further away. So it’s just a device to help you make the film. Once the film is made it has no value whatsoever.

10. Story structure is the key to filmmaking. The rest is just details.

Warner had very little faith in Deliverance because there were no women in the film and, you know, films without women never succeed. So they beat me up on it a lot and made me cut the budget down. So there was not a lot of confidence about it but I think the film had a structure that was very cinematic. And it was a film that, as an audience, you can’t escape it. It dragged you along and you just had to follow it.