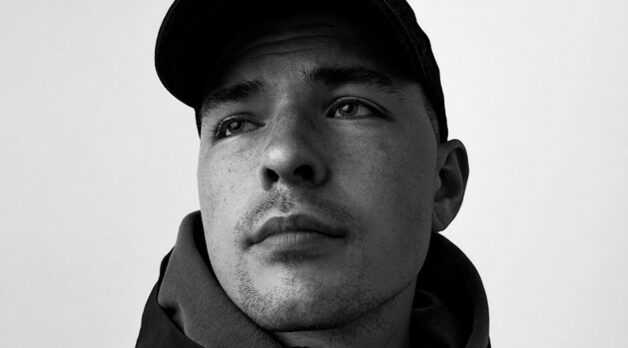

Jared James Lank

Jared James Lank

Jared James Lank

A true one-man production, Bay of Herons begins by presenting an anti-colonialist take on Gluskap, a creator character of the Wabanaki peoples, the Indigenous confederacy the Mi’kmaq nation is a member of. Mi’kmaq tribe member Jared James Lank “filmed, edited, scored and captioned” the short, which uses subtitles to tell a story about Gluskap attempting to fend off French colonialists and then never returning. Hundreds of years having passed since this standoff, the subtitles yield to a narrator who sends up a prayer for strength to Gluskap all the same. Shots from Maine’s Mackworth Island capture the area, which is mostly composed of state parks, through all four seasons, in disciplined landscape Academy-ratio views drawing upon Lank’s background as a still photographer. “The film was actually shot almost entirely with a Sony FX3, and I graded the footage to look like 16mm film as best I could,” he notes. (He succeeded.) Combined with the narration and Lank’s ambient but assertive score, the seven-minute Bay of Herons is a moodily locked-in work that complicates what could otherwise be straightforwardly pleasing nature portraiture. “It’s a reflective visual essay that I made about the idea of reconciling a cognitive dissonance that I feel a lot of indigenous people experience when they’re in their ancestral homelands,” Lank says. “When I think about my traditional culture, I’m describing place and the mythos of place in those deep ancestral histories. When I look at the landscape, I have to reconcile the fact that it has been inextricably changed by colonization. Those dissonances for me are very much embodied in the film.”

Bay of Herons is the latest manifestation of Lank’s lifelong study of the Mi’kmaq experience in Maine. His paternal grandparents migrated from Nova Scotia to Maine, both areas that are part of the Wabanaki’s tribal lands. “My family moving to Maine to be potato and blueberry farmers, then moving to Southern Maine to sell baskets and axe handles, is very common for a lot of the Wabanaki tribes,” he says. Lank himself was born and raised in Arundel, a town close to Kennebunkport. “Maine is often referred to as vacation land,” Lank notes. “I grew up in one of the big tourist destinations in Maine, with working class families. I felt like I watched my whole life get pushed out of their communities because of this inundation of vacationing and tourism commandeering the coast of Maine. It turned it into a place designated as a destination for tourists during the summer; it doesn’t actually work as a proper town.”

Lank focused on the Wabanaki while studying geography and anthropology at the University of Southern Maine: “My family, myself included, feels invisible in the larger society because people so viewed Indigenous or Native American people as a past tense or something they didn’t understand,” he notes. He then “happened to connect with the Upstander Project,” a Boston-based nonprofit organization and socially oriented content creator, “to work on a project they were doing at the time about some history specific to the tribes in Maine. That was my introduction to documentary filmmaking.”

Previously, the idea of filmmaking had seemed out of reach, but thanks to a fellowship with 4th World Media Lab, in 2021 Lank attended the Camden International Film Festival, where Bay of Herons would premiere two years later. In between, he met Sundance programmer and Indigenous Program head Adam Piron. Lank had been meaning to apply to the Indigenous Screenwriting Lab with a proposed narrative feature anyway, but Piron encouraged him to submit his short. Both eventually made the Sundance cut, with Bay of Herons playing at the festival. Lank is now currently part of a fellowship while he works on a feature-length narrative script he says is “based on a story that was handed down through my family for generations—a superstitious scary story that takes place in the region of Maine in the 1700s.”—Vadim Rizov/Image: Jared James Lank