Back to selection

Back to selection

Shutter Angles

Conversations with DPs, directors and below-the-line crew by Matt Mulcahey

“I’m Like a Flare Hunter”: DP Natasha Braier on The Neon Demon

Elle Fanning in The Neon Demon

Elle Fanning in The Neon Demon With the fantastical levels of post-production digital alchemy now possible, there’s an increasing trend toward not committing in-camera. But not when you’re working with director Nicolas Winding Refn, as cinematographer Natasha Braier discovered on The Neon Demon.

“Most of the time directors love all the radical things I try to do in-camera, but then they’ll still say, ‘Just in case, let’s do a safe version.’ Nic doesn’t do that. He’s not scared to not have that safety net,” said Braier. “Instead, Nic says, ‘Give me that times 10. If you’re going to jump, let’s jump even higher.’ That’s why it’s fun and inspiring to work with him. He lets me be the craziest version of me and the best version of me.”

A variation on the Narcissus myth – only with neon-bathed cannibalism and necrophilia — Refn’s latest finds fresh-off-the-bus teen model Jesse (Elle Fanning) arriving in Los Angeles and slowly awakening to the power of her beauty, much to the envious chagrin of her fellow runway walkers.

With The Neon Demon now out on all home viewing platforms, Braier talked to Filmmaker about schmutzing up Xtal Express lenses, hunting for flares, and the Tetris of shooting chronologically. Click on all images below to expand.

Filmmaker: Tell me about your initial meeting with Nicolas Winding Refn, where you listed off all the things you didn’t like about the script and it turned out you’d gotten a fake version.

Braier: The version I read before the meeting had different characters and different situations. Jesse’s character was there, but the representation of the evil, if you want to call it that, was constructed totally differently. There was a character that was doing special beauty treatments with the blood of virgins and she was the one orchestrating all the killing. It was a lot more obvious. The themes were the same, but it was written more as a standard horror movie. I’m not sure if Nic wrote that version to help get the financing, but what I read just didn’t feel like a Nic Refn movie. It was full of explanatory dialogue so you would understand exactly what the characters were thinking. But we were having this great meeting and eventually I said to him, “Everything we’re talking about now sounds great, but it doesn’t sound like what I read in the script.” And that’s when he said, “Oh, that was the fake script.”

Filmmaker: And you accepted the job without having seen the real script?

Braier: Yes. I was driving back home after that meeting and my agent called and said, “Nic loved you and he wants you to do the movie.” And I said, “But I haven’t read the real script yet. [Nic] is finishing a new draft and he’s going to send it in a few days.” And my agent said, “Do you want to wait until then?” And I just said “yes” [to the movie] right then because Nic is a great artist and I knew we could do something very exciting together. But it was a leap of faith. I’d never taken a movie without reading the script before.

Filmmaker: Refn is known for shooting in continuity. How did you enjoy that process?

Braier: I thought it was amazing to shoot like that. Now I’m totally hooked on it. Shooting in continuity is sacred to Nic and because he’s his own producer he makes all the economic decisions around being able to shoot chronologically. Shooting that way allows [the movie] to change organically and evolve during [production], but you still need to do a lot of prep and be organized. For the beginning of the movie, for example, we had to use the same location for the photography studio where Jesse is being photographed, the make-up room where she meets Jena Malone’s character, and then the party because we had to shoot those three things on the same day and you don’t want to spend your entire day doing long company moves. So there’s a lot of Tetris that happens with locations in prep.

During that process of finding the right locations Nic and I talked a lot about shots and I took a lot of photos with [director’s viewfinder app] Artemis and I did these storyboards with photos and notes on my iPad. So we had a base idea for how we planned on approaching each scene. Then during the process of filming, because we had the luxury of adapting because we’re shooting chronologically, some scenes go out the window completely or characters that were going to die suddenly get very popular with us, so we decide they’re going to live. But you have to have an “A” plan and then you can throw that “A” plan out of the window if you find new things.

Filmmaker: Had either you or Nic worked with much of the crew before? Knowing crew folks, I can imagine everyone bitching about coming back to the same locations over and over.

Braier: It was mostly an all-new crew for both of us. It was hard at first. You know how electricians and grips are: “Why do we have to go to the hotel five times? Why can ‘t we do this in two days and only rent the crane one day if we don’t have any money?” It’s hard for people to understand it because filmmaking has been ruled by the “time is money” paradigm for so long that it’s the way we all think. But after two weeks the crew got it. They saw Nic changing ideas and things evolving organically and they loved it, because they saw how it gives you this artistic freedom. Then they embraced it for the rest of the shoot. So there’s a little bit of resistance at the beginning, just like with anything that is unknown and different.

When I meet other directors now about movies and I ask, “Are you going to shoot chronologically?” they look at me like, “No, we can’t do that. We don’t have the money.” And I’m like, “We did it [on Neon Demon] with five million.” People don’t even consider that possibility because we’ve been taught to do movies in a certain way.

Filmmaker: Let’s get into your choice of lenses – the Xtal Expresses. These are old Cooke spherical lenses from the 1930s that were rehoused and adapted with anamorphic elements in the early 1980s by Joe Dunton. I know you tested lenses before going with the Xtals. What did you test them against?

Braier: Nicolas was determined to shoot digitally and that was a bit scary for me, because I hadn’t shot a feature on digital before and this movie was so much about beauty. I thought I needed the oldest possible lenses I could find to help the faces [look more beautiful]. We needed to portray Elle Fanning as this perfect virgin beauty that just wakes up without make-up and looks amazing and it’s sometimes tough with digital to photograph beauty. You have to do a lot to soften it, so I tested every single anamorphic lens I could find that was old and soft.

I knew I would really love the Xtals because I’ve used them a few times in the past. I grew up in film school in England and I lived there for 10 years, so I knew Joe Dunton very well and I was always using his lenses and whatever new inventions he had. But I still went through the whole process of testing everything. When we saw the tests on the big screen there was nothing as beautiful as the Xtals. They are just so flattering. They break the light in a way that makes skin look like it’s been Photoshopped. Nothing else gave us anything near that look. Those lenses are very special unique jewels.

Filmmaker: In the American Cinematographer Magazine piece on the film, you said that 99 percent of Neon Demon’s flares were practical. What was the 1 percent you couldn’t get on set?

Braier: It wasn’t that I couldn’t get them, it was that Nic thought about adding them after we were done shooting. I can get any flare. I’m like a flare hunter. (laughs) The scene at the party when the [models] see this Japanese bondage art and the light starts to strobe, there were a couple of close-ups on Elle that had a natural flare from the strobe. When Nic cut the movie together he loved those flares and he wanted to add [a similar flare] in all the shots in that scene.

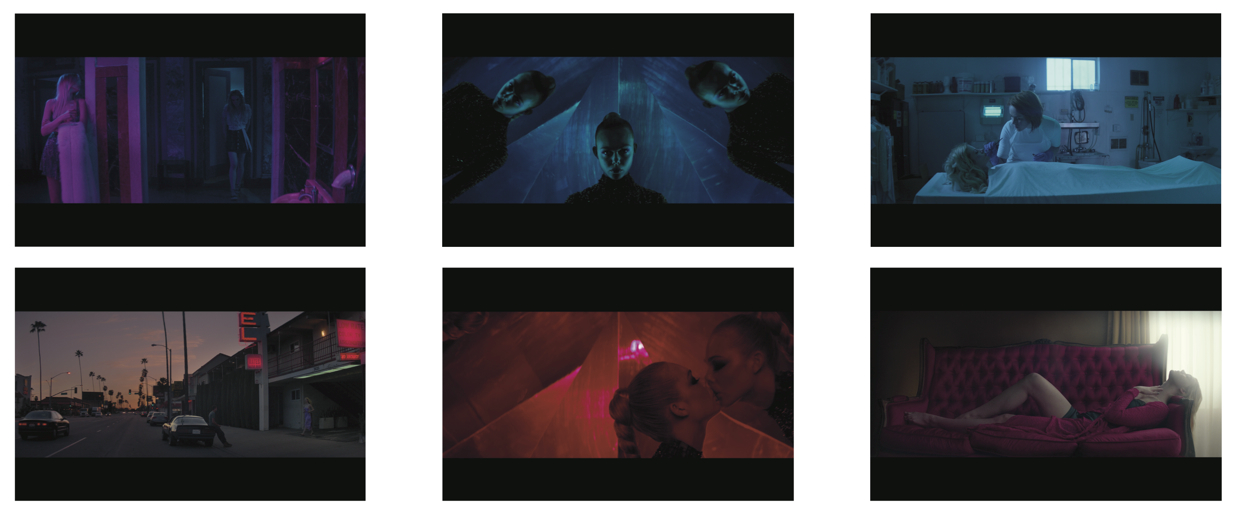

Filmmaker: Let’s look at some of your work from the film. I’ve put together a few clusters of frames to highlight certain elements of movie, with the first set highlighting the color palette.

Braier: Nicolas loves blue and red, amongst other reasons because he’s color blind and those are the colors he sees, so he wants a lot of them. I slightly adapted his normal color palette to what I felt resonated more with me and with the world we were shooting. I think my reds are a little bit more magenta and pink than the primary red that he normally uses. With the blue I went more turquoise and more toward violets and lilacs.

Filmmaker: Talk about how the colors function thematically – as we see in the center frames in the cluster above. There’s a shift from blue to red as Fanning has an awakening to the power of her beauty while on the catwalk of a fashion show.

Braier: Conceptually Nicolas knew he didn’t want to see a catwalk and an audience. He wanted it to feel more like an internal journey for Jesse. It’s also the moment in the movie where we make a very straight reference to the Narcissus myth, which is a very big part of this movie about narcissism. We wanted to turn the fashion show into an evocation of that myth. We went through a lot of ideas and designs, and of course we were a small budget movie so we couldn’t really build the most amazing Alexander McQueen version of this idea, which is probably what we would’ve done if we had the money. So we had to think about going very conceptual with it and we ended up with this fashion show that is mainly done with light and color. There’s hardly any set design there. I’ve always been a very big fan of James Turrell’s work and [Neon Demon’s production designer] Elliott Hostetter was also really inspired by him so we started to look at [Turrell’s] work. It’s very minimal and there’s something very ritualistic about it. Once Jesse [reaches the end of the runway] it symbolizes her reaching the pond and looking at her own reflection. The color transitions from blue to red as Jesse comes alive as this empowered woman that has somehow lost her innocence.

Filmmaker: After that transformation at the fashion show, there’s almost an inversion of the earlier color dynamics. Both the images on the far right in the first collection of frames above are taken from a scene that crosscuts between Jesse embracing her newfound sexual empowerment and Jena Malone’s character longingly touching one of the bodies at her job at a mortuary. Jesse is now in red and Malone in blue.

Braier: We had this idea that every time Jena Malone was in the frame early in the movie, there would be a little bit of red — most of the time in her wardrobe but sometimes in the light or a prop – because she’s the link to the danger. But you’re right, at this moment in the movie, the roles of Jesse as this innocent virgin and Jena as the predator are inverted because Jena’s (advances) were rejected by Jesse.

But it’s also a love scene and I wanted to feel very close to Jena in that moment, because she’s someone who is very lonely and she needs human contact and here she’s having it with this dead body. Her character is coming from a very fragile and wounded place. I tried to do something with the color that was cold and clinical, but at the same time was pleasing to the eye. Jena looks beautiful in that scene. It’s low-key and intimate and I guess it’s as romantic as lovemaking with a dead person in a morgue can be. (laughs)

Filmmaker: I chose this next frame because I read you would sometimes put schmutz – like Vaseline – onto the lens, which it looks like you’ve done here.

Braier: That’s another example of the beauty of shooting chronologically. I started the film tiptoeing around the Alexa, but as I got more confident with the Alexa and understanding how the lenses and that camera work together I started getting a little crazier visually, which works because as the film evolves it gets crazier. So I started to play more and more with flares and putting [stuff] on the lens.

I think the first time I did it was when Jena Malone is having a meeting [with two models] at this restaurant and I did it just because I was seeing too much information through the windows, too much detail. I wanted it to be more abstract so I put some Vaseline on the lens just to blur the window a little bit. So I started to do it by necessity and then I fell in love with it and used that technique more and more.

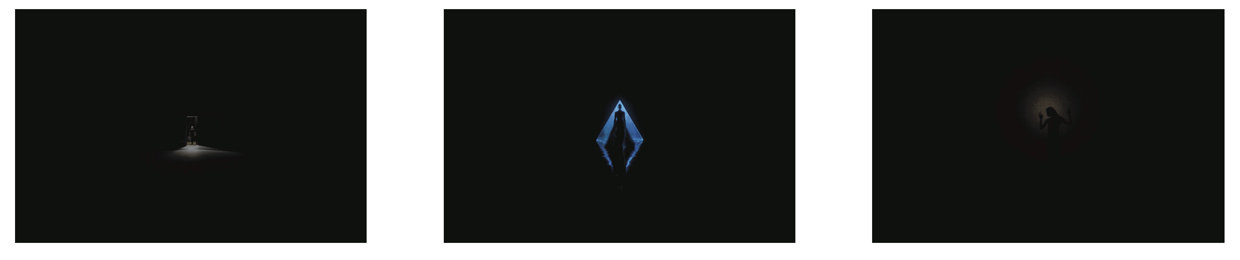

Filmmaker: Next let’s look at these three shots that are all symmetrically centered slivers of light surrounded by complete darkness.

Braier: You know, I have never looked at all three of them together like this. Yeah, it’s very interesting. I don’t know that I had connected them before. A lot of the film is about light and darkness and how all this darkness makes the light seem to shine brighter. So these shots fit [thematically]. Now that I’m seeing the images, these are also all key moments in the film for us. The fashion show is Jesse’s moment of transformation and the one on the far right is a moment that we called “Alice in the Rabbit Hole,” which is another punctuation moment where the movie shifts. From that moment on the movie takes another tone and it goes more into the world of Suspiria and these crazy horror films from the 60s and 70s that Nicolas loves so much. There’s a dreamy quality to the last part of the movie that’s a little bit surreal.

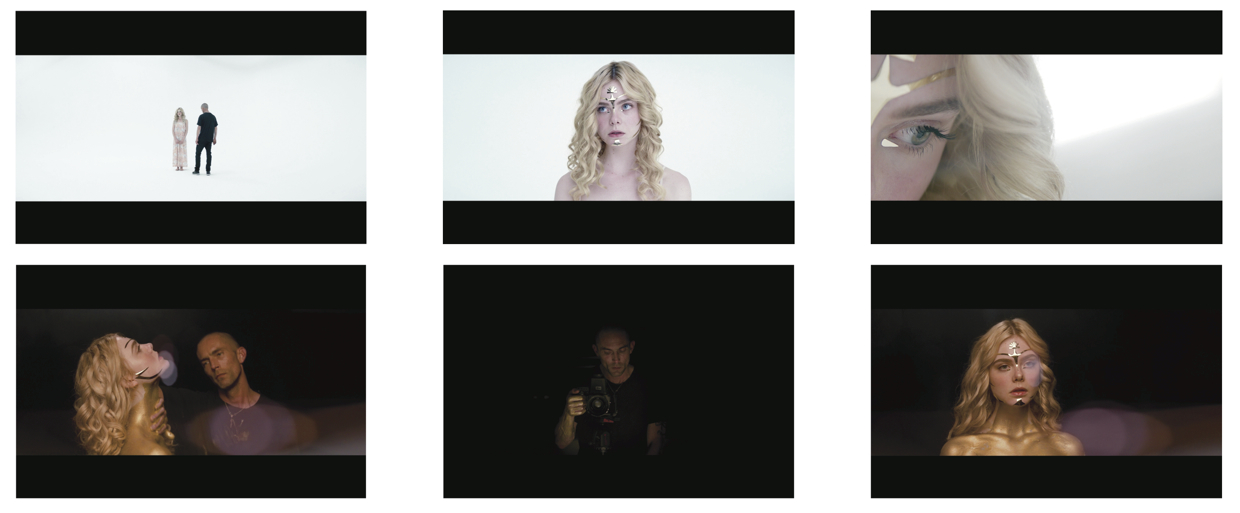

Filmmaker: We’ve talked a lot about the color in the film, but the scene pictured above where Jesse has her first major photo shoot is notable for its lack of color.

Braier: That had to do with the location scouting process. We saw a lot of photography studios and it was hard to find something that felt right. When we saw this one we really liked the idea that everything was so white — not just the cyc but everything in the studio. It worked really well conceptually because it’s the white canvas of everything that’s possible. It’s the idea again of the light and the dark and how this world, the world of Hollywood and the fashion world, promises you this antiseptic, clinical perfect white world with perfect people and no wrinkles.

Filmmaker: I almost forgot to ask you about the mountain lion that shows up in Jesse’s dive hotel room. The shot is fairly dark, but that definitely looks like a real mountain lion.

Braier: It was a real one.

Filmmaker: Was that a set or an actual hotel room?

Braier: No, that was the real hotel. (laughs)

Filmmaker: They let you put a mountain lion in the room!

Braier: Yeah, they let us do anything we wanted. (laughs) It was really funny because Keanu [Reeves, who plays the hotel manager] would just come to the hotel for like two or three hours, shoot his scene, and go back home. I don’t know how many directors could pull that off, shooting in such a gritty location and getting a Hollywood superstar to come and do three hours and then come back again a few days later for another few hours. But Keanu loves Nic’s work and he’s also a great filmmaker so he understood it.

Matt Mulcahey writes about film on his blog Deep Fried Movies.