Back to selection

Back to selection

Shutter Angles

Conversations with DPs, directors and below-the-line crew by Matt Mulcahey

“Was Everything in Focus?”: Wonder Woman DP Matthew Jensen on Shooting 35 and Digital and How Tequila Sunrise Inspired His Career

Gal Gadot in Wonder Woman

Gal Gadot in Wonder Woman I have to admit I can no longer distinguish 35mm film from high end digital cameras when I go to the movies. I can spot 16mm or anamorphic lenses, but the line between digital and 35mm celluloid has become impossibly blurred.

Wonder Woman cinematographer Matthew Jensen can still spot the subtleties, but for Jensen the aesthetics of film are only one of the reasons he enjoys working in that format.

“It’s very hard to tell the difference, especially when you’ve gone through a DI (digital intermediate) process and you’re projecting digitally. We have some shots that are digital in Wonder Woman and I think you’d be hard pressed to tell which is which,” said Jensen. “I think film is kinder to faces than digital, but aside from that, I enjoy the process of working with film. There’s something so nice about not being tethered to a monitor. I’m more present on set when I’m shooting on film.”

With Wonder Woman holding strong at the box office nearly two months into release, Jensen spoke to Filmmaker about crafting a superhero movie that has become not only the savior of the Warner Bros.’ DC universe but also an unlikely gender equality rallying cry in the current culture wars.

Filmmaker: Your official bio says you got into filmmaking as a kid through classes at the Smithsonian. Tell me about that.

Jensen: I became interested in movies very early, like a lot of guys from my generation that I went to film school with. We all caught the bug early. I got my first Super 8 camera when I was about 11 and recruited kids in the neighborhood to be in these little movies. My family were members of the Smithsonian and it offered a ton of classes for kids, including filmmaking classes. So by 12 or so I was taking all sorts of courses at the Smithsonian that ran the gamut from stop motion animation to what I would call critical film studies, where we watched clips from movies and broke them down.

I also went to a filmmaking camp that was like three weeks long. During the last week of camp we all made a movie. My instructor at that camp was an avid amateur filmmaker and he belonged to this society called The Super 8 Widescreeners, a collection of amateur filmmakers from all around the country that would shoot films in this weird Super 8 anamorphic format and then mail those films to each other, passing them from one person to the next. He had this whole basement setup to screen movies and cut film and he had all these great movie books. He invited a few of us from that summer filmmaking camp to his house to edit the film we had shot. The screens [on his editing machines] were small and hard to see and you were literally marking your cuts with a grease pencil on the film, then splicing and hand-taping everything together. There was a wonderful tactile quality to all of it. By the time I was 14 or 15 I had a ton of hands-on experience actually handling and cutting film.

Filmmaker: At that early stage were you already gravitating toward working with the camera?

Jensen: I think that came later for me. I was always interested in the visual aspect of filmmaking and gravitated to it naturally, but entering film school I thought, “Well, I’ll just be a director.”

Filmmaker: Seems like that’s what most people think when they start film school.

Jensen: Yeah, when you’re 18, what do you know. (laughs) At film school I ended up reading a couple of issues of American Cinematographer. It was so over my head at the time, but I was intrigued by it. I particularly remember an article about, of all movies, Tequila Sunrise, where Conrad Hall talked about the palette of the film. He described it in terms of wanting warm, natural browns instead of the usual high contrast red and deep blues of police procedurals. And I thought, “Wow, that’s really interesting. The cinematographer does that?” By the time I was really in my film program at USC I was pretty committed to the idea that cinematography was what I was going to do. I just liked being behind the camera and orchestrating the shots and lighting much more than I liked anything to do with directing.

Filmmaker: So basically you’re a DP because of Tequila Sunrise.

Jensen: (laughs) I guess if you want to break it down to that level.

Filmmaker: You can’t always trust IMDB, but it lists the action flick Best of the Best 3 as your first credit. True or false?

Jensen: It’s not me! I’ve tried so hard to get that credit removed, but it just won’t leave me alone. It’s a different Matt Jensen, I guess.

Filmmaker: He’s probably out there right now explaining that he didn’t shoot Wonder Woman.

Jensen: Right. (laughs)

Filmmaker: That seems like a good segue into Wonder Woman. You shot most of the film in 35mm rather than capturing digitally.

Jensen: Both formats have advantages and disadvantages. Film does still have that textural quality because of the grain and I think it works very well for period [settings]. You can obviously grain digital up, but the grain doesn’t move in the same way and it’s not alive in the same way as film. Film cameras are still much bigger than the small digital cameras and all of the technical innovation has gone into moving these small, lightweight digital cameras with things like drones and the Stabileye. You can fly a digital camera around with much less rigging than you can with a film camera.

For the camera assistants, shooting digitally is really helpful because they know that they have shots in focus right there on set because they’re working off the monitors. They have to be so much more on their game when they’re shooting film. On Wonder Woman it got to be kind of hilarious because I would go see the dailies every morning before going to set and as soon as my camera assistants saw me they would come running up and ask “Was everything in focus?” (laughs) They were living and dying by my reports every morning. So there are trade-offs with film. But for me, psychologically, seeing film dailies always lifts me up and carries me through the next day no matter how tired I am and you just don’t have that with the digital workflow.

Filmmaker: You have a video tap when shooting film. Is that not very representative of what’s being recorded on the negative?

Jensen: It usually looks terrible. You can see performance but it’s so not representative of color and you can’t even tell if it’s in focus half the time. It’s no way to judge anything.

Filmmaker: Seems like most people pull focus off monitors at this point. Was it hard to find ACs who could still work in the old school way?

Jensen: Both my focus pullers — Adam Coles on B-camera and Sam Barnes on A-camera — came up working with film, so they’re skilled in both formats and they’re both dynamite focus pullers. We did run intro trouble finding experienced loaders. I find that’s the biggest problem, because the loader tends to be the youngest position on the camera crew.

Filmmaker: What situations on Wonder Woman called for breaking out the Alexa 65?

Jensen: We shot some aerial plates with the 65. A lot of the stuff where Steve Trevor [played by Chris Pine] is flying in Turkey was the Alexa 65. And then we shot Alexa SXT for the underwater sequences and for some of our aerials in Italy.

Filmmaker: In terms of film cameras, you used Panavision’s Millennium XL2 and Arri’s 435 and 235. The Millennium was your main camera and the other two are high speed cameras?

Jensen: The XL was our main sync sound camera. We also carried a 435 on main unit to do some slow motion work up to 150 frames per second. The 235 was really used on second unit. They needed a lightweight film camera that they could throw around for some of the fight sequences. My goal was to stay on film as much as we could until it become technically impossible to achieve something. For example, we had to use the Phantom for some of the fight sequences because we were shooting up to 500 frames per second.

Filmmaker: You went with Panavision Primo spherical lenses for most of the film?

Jensen: Yes, for pretty much everything. At the beginning of the 1990s those were the in-demand lenses to use. It’s funny how things change. They are really well engineered and beautiful lenses. They have a sharpness, but they are not brutally sharp. They also have good contrast. I’m a big fan.

Filmmaker: I read an interview you gave for Fantastic Four where you talked about shooting that film mainly with focal lengths between 21mm and 50mm. What about for Wonder Woman?

Jensen: We had a little bit more variety on Wonder Woman. We were roughly in the 21mm-75mm range. There are a couple of shots on long lenses, like 200mm lenses, but that didn’t happen very often. I tended to go a little longer when shooting close-ups than I did on Fantastic Four. Where I might have used a 40mm on that movie, I went with a 50mm or 65mm for Wonder Woman. I try to stay in a limited range because I think it requires more consideration about where the camera goes rather than using a whole bunch of long lenses. And I think [Wonder Woman director] Patty Jenkins gravitates to wider lenses as well.

Filmmaker: I looked at the Kodak website and you don’t really have that many choices any more for your stock.

Jensen: Yeah, they’re all kind of cut from the same cloth now, which is helpful. There’s a great consistency in all of the negatives. It helps you when going through the DI process. For the majority of the movie we used Kodak 5219, which is the 500 speed tungsten stock. I even shot day exteriors in London on 5219 so I could bias the negative to the blue/cyan side of things, which we enhanced in the grade. I used the 250 daylight (5207) and the 50 daylight (5203) in certain sequences, mostly in [Diana’s home world of] Themyscira when I had more sun.

Filmmaker: When you watched your dailies projected, could you see a difference in the grain between the 50D compared to the 500T stock?

Jensen: 50D is less grainy, but you really have to do side-by-side comparisons and work with it every day to see the difference. I don’t think you can see it over the course of a two hour movie, especially if everything is exposed well. And really, by the time it goes through a DI process everything tends to blend together.

Filmmaker: I haven’t seen a film in 3D in probably two or three years and it seems like the percentage of box office generated by 3D keeps decreasing. When a movie is post-converted like Wonder Woman, how much emphasis is put on that aspect during shooting?

Jensen: It’s not being pushed on set. There were really no discussions about it. And the post-conversion process has gotten so good that there’s no real need to put yourself through the headache of shooting in native 3D. But we knew that [the studio] was also going to do a 3D release — it’s just what they do. It’s especially good for China and it’s a way to get a higher ticket price domestically. But I’m not a fan of the format, especially in its current state. [Click on all frames below to enlarge.]

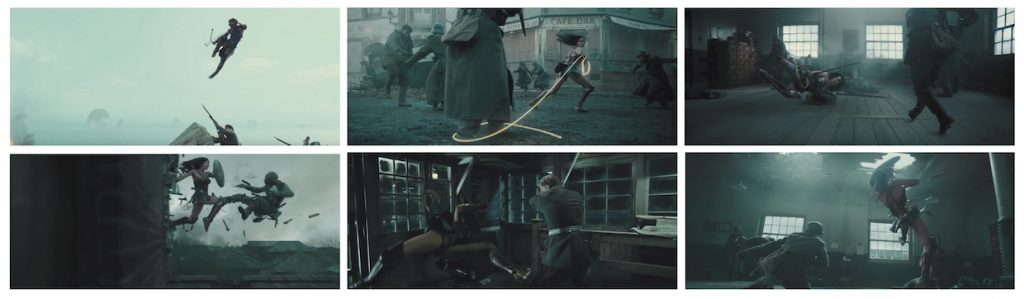

The Frames: A series of Wonder Woman’s slow motion shots.

Jensen: A lot of these shots were done at 500 frames per second and that’s really a technical trick, even on a digital camera like the Phantom, because you need so much light. The interior frames you have here with Diana battling the Germans were all shot on sets with greenscreens out the window. We had to pump in an enormous amount of light just to get an exposure. And I like to shoot with a lot of soft light, so we’re sending our sources through diffusion or using big bounce sources. The minute you do that you’re cutting down the amount of footcandles coming off the source. So you have to bring in even more light.

Filmmaker: All of these slow motion frames have a greenish tint to them. How do you get that color – you can’t just change the Kelvin on a film camera the way you can on a digital one. Do you gel lights, achieve it photochemically, or wait for the DI?

Jensen: It’s a combination. In the Europe and London stuff we lit primarily with either tungsten lights gelled with CTB [Color Temperature Blue] or we lit with HMIs on tungsten film and didn’t correct for it. Then it became a trick of emphasizing the blue and the cyan that were in the shadows on the negative while bringing back the midtones to a more pleasing skin tone color.

Filmmaker: During the photochemical portion of post, do you try to process as neutrally as possible and then make most of your tweaks once the film has been scanned in for the DI?

Jensen: No, I try to get it as close to the final look as I can photochemically, while knowing that I have the digital tools to take it even further in the final DI. The great thing about the digital intermediate is that you have more sophisticated and subtle control over the highlights, the midtones and the shadows. What we ended up doing is biasing the shadows more toward cyan/blue and the highlights and skin tones we made a little warmer, especially for the London and Belgium sequences .

The Frames: The Amazons of Themyscira clash with German forces on a pristine beach.

Jensen: Themyscira is supposed to be an island paradise so we wanted a heavy emphasis on the blues of the sky and the ocean, the greens in the foliage and warm, bronzy skin tones. I shot a lot of this scene on 50 ASA film stock, which naturally has a brilliant color saturation to it, then we goosed the saturation even more in the DI.

There was previs of this entire sequence that went through several different variations and there was also an extensive amount of storyboarding. I would say that 90 percent of the final scene matches the previs, but we had a lot of cameras out on the beach so we were able to find little moments that you can’t plan for. When we joined first and second unit together we had six cameras available to us. This scene also has elements that are purely VFX, completely digital shots where nothing is real. Then there’s shots that are a combination of greenscreen elements that we shot later on stage, just because the stunt performers had to be on wires and we needed the infrastructure of the stage.

Filmmaker: This scene unfolds in a matter of minutes in the film, but it took two weeks to shoot. How did you create consistent light?

Jensen: We had 18Ks and all sorts of artillery out there to help us and there are certainly some shots that are very lit. I also had a big SoftSun that we could move around on the beach but sometimes it proved to be such an undertaking to move that light in the sand that I would get impatient and just shoot without it. If you really analyze the sequence the light does change quite a bit. Luckily the cuts are fast and we were able to even out a lot in the grade. You just have to go with it, especially with the bigger action sequences. Sometimes I could afford to wait for the sun to pop out from behind a cloud, but other times I just had to shoot. You can’t get behind schedule just because you’re stuck in overcast light.

The Frames: Steve Trevor is captured by the Amazons and interrogated with the Lasso of Truth.

Jensen: Patty and I talked about this being a late afternoon look. The lights that you see rigged up above [in the behind the scenes frames] are all space lights through a 50/50 diffusion cloth that’s half CTB and half Light Grid. Then some of those lights were rigged with Cyan gel. That gave me my base exposure, which was about two stops lower than my camera exposure. I also sent in warm light from the right side of the frame. Then I had a Mole Beam gelled with amber hitting the queen and the throne. We also wanted to suggest that there was water running behind the throne, so we had a series of lights that were like gobos that you’d see used at a concert, and we had those bouncing into Mylar so they’d shimmer like light reflecting off water.

Filmmaker: In the behind the scenes frames, what is that light rope that Pine is wrapped up in?

Jensen: That was just an amber LED in some tubing that we could control (remotely) from our lighting desk and change its intensity. We did some tests to arrive at the right color and that was our stand-in for the lasso.

The Frames: Diana attends an opulent party with the intent of assassinating Danny Huston’s German general.

Jensen: This was one of the most challenging locations for me. It was a place called Hatfield House in London. It’s an old manor and historically very important, so we weren’t allowed to do any rigging. There were windows in the room but we were shooting in London in winter, so I couldn’t rely on the sun to always be out. I wanted this scene to have a cooler, dusky feeling, so we put up Ultrabounces — I think they were 20’ x 40’ — across the length of this hallway and then bounced 20Ks that were gelled half-blue into them so we’d have a dull glow coming through the windows. Then I consulted with the art department to put a lot of practical shaded lamps in the frame, and from there I just went about augmenting those practicals. In these wide shots I used 4’ Kino tubes that were hidden just behind the recesses of the windows and those gave Diana a soft side light. And then we had a China ball walking with Diana to wrap a little light on her face. I think I shot this at a 2 2/3 stop. I never like to open up beyond a 2.8 but here I just had to. It was really tough on the focus pullers, but they did a great job on that sequence.

The Frames: Diana (played by Gal Gadot) scales a tower in order to acquire her sword and shield.

Jensen: I always grit my teeth and cringe when I have to shoot a sequence that takes place at night in a location where there isn’t any noticeable source of light because you have to be reliant on moonlight, which is inherently fake. It’s a tough thing to pull off. You want to be able to see the action, but you also want it to be dark enough to feel natural. To create this soft moonlight effect I used a 20K gelled with half blue with a little diffusion in front of it to soften the shadows. We tweaked that light to be a little bit more cyan in the DI. Stefan Sonnenfeld from Company 3 did a great job coloring this.

The camera is on a remote head crane and Gal, who did a lot of her own stunts, is supported by wires, but it’s supposed to look like she’s powering herself up this tower. We had to be really careful in the angles we used and when we chose to use the stunt performers. It all becomes a big dance.