Back to selection

Back to selection

La Chinoise, Le Gai Savoir, Personal Shopper and Two by John Sturges: Jim Hemphill’s Home Video Picks

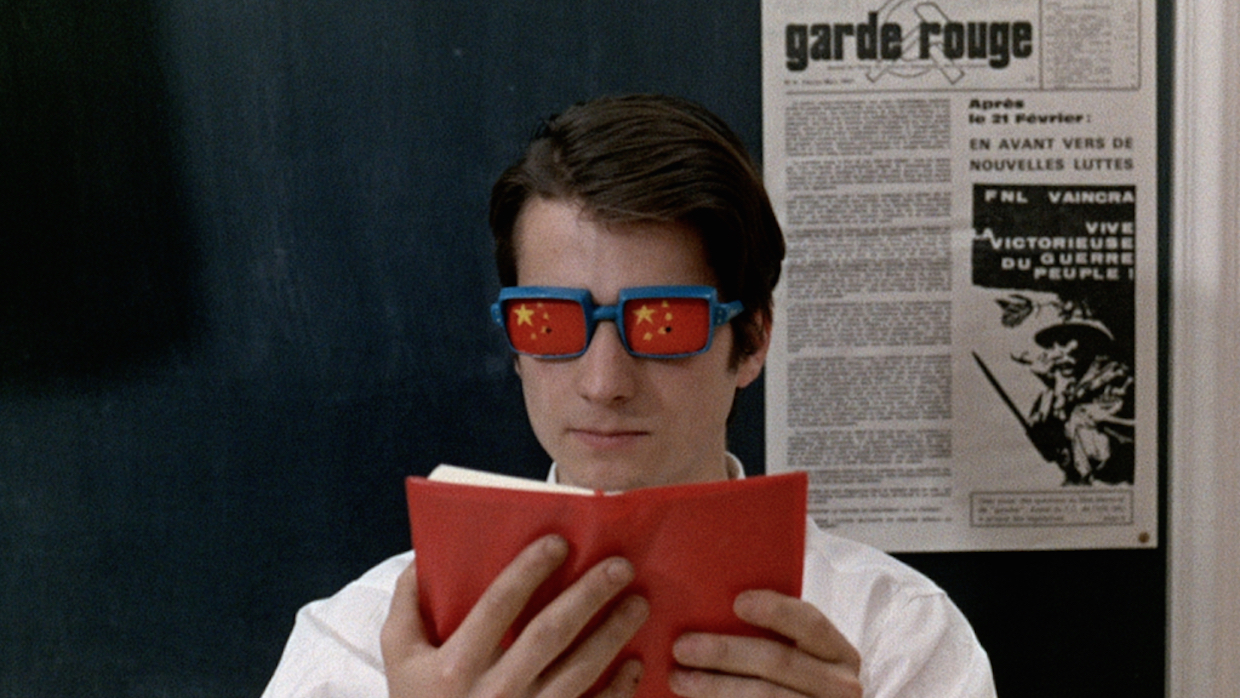

Jean-Pierre Léaud in La Chinoise

Jean-Pierre Léaud in La Chinoise “How has La Chinoise aged?” asks Amy Taubin in her liner notes to the new Blu-ray edition of Jean-Luc Godard’s 1967 provocation. Elsewhere in the disc’s accompanying booklet Richard Hell examines how he has shifted positions from seeing La Chinoise as lesser Godard to “a glorious experience” superior to more easily accessible works like Pierrot le fou. Both critics circle around one of the things I find most fascinating about Godard in general, which is the fact that his movies, more than those of any other filmmaker, seem to change the most drastically from one viewing to the next. Of course, the films aren’t changing – we, the viewers are – but somehow Godard’s method inspires continual reappraisal and forces the viewer to actively reconsider not only the work but his or her shifting responses to it. While I find virtually all of Godard’s oeuvre worthy of close study, my personal favorites among his films change drastically from year to year in a way that doesn’t happen with, say, Scorsese or Bergman – depending on where I’m at in my life, and where the culture is at as a whole, I can run hot or cold on Le Mepris, Pierrot le fou, Tout va Bien, Hail Mary and most of the others, responding passionately on one viewing and wondering the next time what the hell I ever saw in the film (and vice versa).

La Chinoise is a perfect case in point; the story (if that’s even the right term — it’s more of a notebook or essay than a conventional narrative) of a group of leftist students who take militant action to upend the existing power structures, it has alternately come across as superficial and provocative over the course of my 25-year relationship with it. Part of this is built into the structure of the film itself, which revolves around debates and digressions that often give equal weight to contradictory arguments, and some of it has to do with the characterizations of the students, whose behavior is impassively documented by Godard’s detached, purposefully deglamorized camera. Are we supposed to find their passion righteous, silly, misguided, frightening, admirable or all of the above? The movie rarely gives answers to the questions that it raises, though Godard does subtly use screen grammar to give us hints, as in a lengthy debate on a train in which the character with whom he agrees is facing the “right” direction. Revisiting the film today, during the most chaotic – borderline apocalyptic – period I’ve ever lived through, La Chinoise comes across as more vital, illuminating, and accurate in its observations about politics and human nature than ever before. It also clarifies much of what Godard did in the ten years or so afterward, as he left the trappings of genre behind for good in favor of a quest for a purer cinematic form that would convey the moral and philosophical ideas to which he was becoming committed; the three movies Godard made between 1967 and 1969 — La Chinoise, Weekend, and Le Gai Savoir — would mark a definitive break with the ties the former critic once had to the Hollywood auteurs and conventions he celebrated in his writings for Cahiers du cinema.

Le Gai Savoir, which like La Chinoise is newly available on Blu-ray from Kino, is perhaps the most radical of the three films, a 92-minute meditation on the question of how to tell the truth using a language – the language of cinema – that Godard had come to believe was built on comforting, dangerous lies. It’s less a movie than a prelude to a movie (to a whole series of movies, in fact, the ones Godard would make throughout the early 1970s), a prelude that asks what movies are, what they do and why. Like La Chinoise, it’s dense with literary and historical allusions as well as contemporary political references, and without the signposts of crime films, melodramas, musicals, and science fiction that Godard’s earlier movies provided, it can be a bit daunting for contemporary viewers. Thankfully, the new Kino Blu-rays of these Godard classics both include outstanding commentary tracks that provide context for the under-informed: James Quandt serves as tour guide for La Chinoise, and Adrian Martin provides a narration for Le Gai Savoir. Both commentaries are comprehensive and accessible and serve as terrific introductions to two seminal works in the career of one of the most influential and endlessly intriguing filmmakers who ever lived.

Another Cahiers critic who successfully transitioned into a major filmmaking career, Olivier Assayas, gets the Criterion treatment for the fourth time with the label’s exquisite new Blu-ray of his most recent film, Personal Shopper. Assayas deservedly won the best director prize at Cannes last year for this impeccably calibrated blend of psychological thriller, somber character study and spiritual contemplation, in which Kristen Stewart plays a self-proclaimed medium mourning the death of her twin brother. As an elegant, haunting evocation of grief and longing, it’s a supremely effective and tantalizing mystery, but what gives Personal Shopper its added kick is the self-aware way in which Assayas uses Stewart, who won a Cesar Award under his direction for Clouds of Sils Maria. In that film she plays a personal assistant to an aging movie star; here she’s a personal shopper for another rich and famous celebrity. It’s strange and intriguing to see Stewart, who became one of the most famous actresses in the world after Twilight, playing characters who reside in fame’s shadow – it adds to the psychological tension while also commenting on how ill-suited Stewart was to the role of red carpet starlet to begin with. In keeping with Criterion’s usual practices, the Blu-ray transfer is flawless and there’s a great interview with Assayas in which he delineates the film’s intentions and themes; it’s one of three indispensable titles released by Criterion this month. The other two, Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon and Orson Welles’ Othello, probably don’t need a lot of help from me to find eager consumers from the world of cinephilia; I’ll just say that both discs are even better than one would hope, with hours of compelling extra features and, in the case of the Welles picture, multiple cuts and a whole additional feature, Welles’ Filming Othello, which has been relatively inaccessible in the U.S. until now.

My final recommendations this week are two lesser-known Westerns by the great John Sturges (Bad Day at Black Rock, The Magnificent Seven, The Great Escape). A hugely popular filmmaker in his time, Sturges has largely been eclipsed by contemporaries like John Ford, Anthony Mann and Budd Boetticher among Western devotees, but at his best he’s a richly ambivalent visual stylist capable of creating legends and demolishing them with equal skill. His 1967 masterpiece Hour of the Gun is a case in point. It’s a kind of companion piece to Sturges’ earlier hit Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (1957), which told the Wyatt Earp story and climaxed with the famous confrontation referenced in the title. That movie was a fairly traditional (if expertly executed) Hollywood myth in which the moral lines were clearly drawn; Hour of the Gun, which begins with the gunfight at the O.K. Corral and then devolves into a chilling downward spiral of vengeance and bitterness, is all shades of gray – maybe even shades of black.

Viewers who know James Garner only from his amiable turns in Murphy’s Romance and The Rockford Files will be startled by his grim, obsessive take on Earp, who is presented not as a hero but as an angry avenger who uses his badge as a weapon. (One of the best lines in the movie comes from Jason Robards as Doc Holliday: “Those aren’t warrants you have there. Those are hunting licenses.”) Sturges and screenwriter Edward Anhalt give us a West made up of petty street fights and ruthless businessmen who build the country more through bribery and abuse than industriousness or all-American ingenuity. It’s a bleak but utterly convincing vision that paves the way for Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch two years later — that film would share a number of cast and crew members, as well as a hostile and forbidding treatment of landscape, with Hour of the Gun — as well as Lawrence Kasdan’s 1994 epic take on the Earp-Holliday-Clanton saga, the underrated Wyatt Earp. Twilight Time’s new special edition Blu-ray of Hour of the Gun is limited to a run of 3000 copies, so I’d suggest grabbing it from the label’s website sooner rather than later.

I’d also highly recommend Warner Archive’s new Blu-ray of another Sturges gem, the lean and mean 1958 oater The Law and Jake Wade. Clocking in at a tight 86 minutes, it’s less obviously revisionist than Hour of the Gun but just as dark and subversive in its own way. The morality is once again less black and white than just plain black, as reformed ex-thief Robert Taylor is sucked back into violence and crime when he reunites with his old partner in stagecoach robbery, played with typical slimy relish by Richard Widmark. Taylor’s a bit too wooden for Sturges to fully explore all the ethical quandaries in William Bowers’ script, but the expressive CinemaScope framing (gorgeously presented on Warner’s pristine new transfer) and dynamic supporting cast (Henry Silva, DeForrest Kelly) more than make up for the void at the story’s center.

Jim Hemphill is the writer and director of the award-winning film The Trouble with the Truth, which is currently available on DVD, iTunes, and Amazon Prime. His website is www.jimhemphillfilms.com.