Back to selection

Back to selection

Eileen Yaghoobian, Died Young, Stayed Pretty

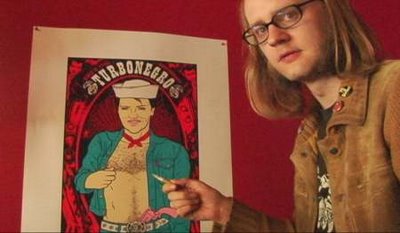

POSTER ARTIST ROB JONES IN DIRECTOR EILEEN YAGHOOBIAN’S DIED YOUNG, STAYED PRETTY. COURTESY NOROTOMO PRODUCTIONS INC.

POSTER ARTIST ROB JONES IN DIRECTOR EILEEN YAGHOOBIAN’S DIED YOUNG, STAYED PRETTY. COURTESY NOROTOMO PRODUCTIONS INC.Eileen Yaghoobian, as she puts it, loves making pictures, and over the years, the Iranian-born, Canadian-based artist and filmmaker has put her energies into doing that in a number of different ways. She first discovered her creative impulse as a fresh-faced teenager when she saw Antonioni’s Blow Up and was inspired to take up photography. She then earned an MFA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, where she gained experience in filmmaking, 3D animation and theatre as well as photography. For many years, she was best known for her photography, particularly her grid pieces which composited thematically linked images, and had her work in the permanent collections of such esteemed institutions as George Eastman House International Museum of Photography and Film, the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston and Paris’ Bibliothèque Nationale. Parallel with her career as a still photographer, she worked in U.S. and Canadian films in roles such as costume designer on Rock ‘n’ Roll Frankenstein (1999) and set decorator on Boricua’s Bond. Not long ago, Yaghoobian also began working in theater: she recently directed a Boston production of Tennessee Williams’ The Night of the Iguana and in 2008 participated in the Lincoln Center Director’s Lab.

Yaghoobian’s first feature, the documentary Died Young, Stayed Pretty, arose out of tragedy, as she began making it after the death of one of her brothers. The film is about the indie rock poster community that exists around gigposters.com (a website that Yaghoobian discovered during her period of mourning), a group of artists who make inspired, idiosyncratic work for one-off gigs, for little or no money. What’s most distinctive about Died Young, Stayed Pretty is the way in which it completely eschews traditional documentary conventions: there is no narrator, no introduction or exposition, no clear form. The film is a work of art similar to the posters it features, impressionistic rather than formal, with Yaghoobian placing images and interview footage together to create an overall ambience rather than an informative narrative thread. Its looseness is starkly in contrast to a film like last year’s Beautiful Losers – a doc which also portrayed rock-influenced art movement – yet the poster art, and stories told by its makers (such as Art Chantry and Brian Chippendale), render this a strange but strangely compelling viewing experience.

Filmmaker spoke to Yaghoobian about the trauma behind her film’s genesis, the unusual approach she took in arranging her footage, and her desire to go back in time in order to learn to surf.

Filmmaker: What initially prompted the decision to make this film?

Yaghoobian: This is my first feature film, but I’ve been a shooter for 20 years. I’ve been a photographer, I’ve been making shorts, I’ve done 3D animation, I’ve worked in theatre, so I’ve done many different things. My base was photography – I’ve had shows and I’m known as a photographer – but meanwhile I was also making films, like short video art projects or Super 8 films. I had this grant to live in my van for eight months and travel the States, and I made 20 short films out of that with my Super 8 camera. They were about this alien that had landed on earth that was this useless superhero. [laughs] This is the first time I went for it and made a feature. The transition for me was in 2004, when I had two things happen to me. First, that Yippi Yaghoooooo alien piece got into the Phoenix Film Festival, which was crazy and ridiculous at the same time. I went to a screening there and I just loved the immediacy of the audience and the response they had. It was like a comic piece, a hurrah to the silent movie era, so people were responding to it. Secondly, I had a solo show in Tribeca at the same time, so I flew from Phoenix to New York for my show. I just decided that my audience is the film people because I related more to them than to the art community. At that point, I decided that I wanted to be making films.

Filmmaker: There’s a pullquote that describes the film as an outlaw movie about outlaw artists. Did you feel very much outside of the filmmaking community?

Yaghoobian: Outsider, yes. I made this without any kind of rules that I was supposed to follow as far as waiting for financing, [laughs] which is what most people do. I did this out of my pocket and I traveled solo: I was completely alone shooting for three years on location. I did the sound, I did the filming, and the deal was that I would show up to the artists’ towns if they’d put me up. I slept on their floors, I slept on their couches, sometimes I was drunk when I was shooting, and basically I was there all the time at all times. With some people, I spent 10 days with them and I was there 24/7, some people I was there for 20 days. It wasn’t like I went to the town and showed up at the studio and talked to them for three hours, I was actually living with them in their house. It was a more personal film for me in that way. I didn’t want to make a film where I said, “Here are these artists and they’re just pimping themselves.” I wanted to really be transparent. It’s a representation of you as a director, and you can tell when someone’s bullshitting on the screen – it’s called bad acting! [laughs] And it’s the same with real people exactly the same as it does with actors.

Filmmaker: Were you able to devote your time fully to the film, or did you have to take breaks to make money to keep yourself going?

Yaghoobian: It was a back and forth, but it was a back and forth with no breaks. It’s not like I went away and wasn’t on the project; I went away and was dealing with the footage. [laughs] It was like 250 hours of footage, I went to 20 or 30 states – it was the real deal. It wasn’t like I went on vacation or anything, I didn’t have a single break. I didn’t have a Christmas or a holiday for four years. I was constantly on location filming, and I was alone, which made it harder. It makes it fully harder when you’re on your own.

Filmmaker: With so many hours of footage, and with the unconventional approach you took to presenting the material, it must have almost felt like there was more than just one movie you could have made from what you had.

Yaghoobian: Oh, yeah, oh God, yeah. There were five movies I could have made out of this film, because I covered my ass. I covered myself while I was filming so I could have the film that is the history of rock posters, so that I could have the film that has that battle between two big rock poster dudes. [laughs] I covered all of those angles, but this is the film I wanted to make. What connected me on a deep, gut, instinctual level was the dialogue that lives in the posters and the posters themselves. I did this all very planned and clear, knowing exactly what I wanted. I was very well prepared. I had a shot list of every person I interviewed and I knew exactly what they made and what they said. I really did a lot of my research on gigposters.com, I’d read pretty much everything each one of them had said and written and I knew the conversation within that community. So when I went to talk to each person in their locations, I was very prepared for them and what I wanted from them.

Filmmaker: What would you say your conception of the film was going in? Did you have any specific structural ideas about how you wanted to approach the material?

Yaghoobian: When you talk about “outlaw,” I really did cut this to the antithesis of that pace and tone that most documentaries have. Most documentaries, they ease you in, they prepare you, they teach you. [laughs] I wasn’t interested in that. Maybe because I come from a heavily art-oriented background, I really felt like I had to serve the material and give up to it. At the time I started filming, my second brother had died and my friend had sent me a link to gigposters.com. I instantly related to the imagery, the twisted irony and the satire and the dark humor, and on a gut level that was what drove my craziness to do what I did. It has been five years of my life, but that’s what drove my interest. Structurally, I wanted to cut it like a rock poster, I wanted to make it like I was cutting and pasting a rock poster.

Filmmaker: When people ask you what your movie’s about what do you tell them? To me, it’s a lot more complex than just being about rock posters.

Yaghoobian: I say it’s about the community of rock posters, about the cultural dialogue that lives in the posters and the community. Of course, these documentary people watch the movie and say, “Where’s the narration?” And then people are like, “How come we didn’t see more process?” I’m not making a movie to teach you how to make a silkscreen poster – go pick up a book. That’s not what I’m interested in. Sometimes people get irritated when artists are telling their views, saying they’re blabbering on about what they think. It’s like, “Why shouldn’t they? Isn’t that the whole point that they’re supposed to be doing that?” They come from this punk angst background, so of course punk is anti-narrative. It’s supposed to deconstruct narrative, so my movie has to serve that. I had to serve it. How could I make a movie about punk and about that feeling of music and then create a narrative around it? It would have just been not truthful.

Filmmaker: Did you ever have pressure from anybody to take a conventional approach? To have a voiceover, to guide the viewer gently into the movie?

Yaghoobian: Oh yeah, I’ve had that. One guy was like, “Yaghoobian couldn’t organize her material into a viable structure.” [laughs] I’m like, “What are you talking about?! I edited for an entire year. I definitely knew what I was going for.” “Viable structure” means what? The movies that person liked would have bored the hell out of me, but they think it’s a “mess.” It’s a conversation: you either follow it or you don’t, you’re either with it or you’re not.

Filmmaker: Some of your photographic art is all about grids of images, so rigid structure and form is something that you actually know very well in your work. Except that here you chose to go for an organic, punk feel.

Yaghoobian: It looks organic, but that thing is cut to a T. [laughs] I cut this movie to the most I could cut it. Oh my God. I think as a photographer and as a director – I’ve worked in theatre as well – I’ve come to really trust my gut. Being an artist (I’ve never liked calling myself that…), you really have to trust yourself in your choices. When I was making this film, there were some amazing things that happened that are just the gifts of documentary filmmaking, and that’s just what happens when you do location filming. I know that from photography, that certain things just happen and it’s about that moment. It’s those little moments that drive you to make a movie for five years.

Filmmaker: You talked about the death of your second brother occurring just prior to you starting this movie. Did that event prompt you to make Died Young, Stayed Pretty? And to give it that title?

Yaghoobian: OK, the title means three different things. And that’s another criticism: “The title has nothing to do with the movie…” I’m like, “What is rock ‘n’ roll?” The whole idea of stars like Elvis dying young is a cliché of rock, but the title in fact comes from me reading Julie Lasky’s book called Some People Can’t Surf about Art Chantry. When I was reading that book researching Chantry five years ago, there was a part where Chantry had made a poster of Marilyn Monroe that read “Marilyn Monroe: She died young, stayed pretty.” Of course, I instantly connected on many levels to the title, and I was like “That’s it, that’s the title of my movie,” so I actually had the title before I shot it. Also, at the time I was in my brother’s apartment, I was grieving and it was my second brother who had died. He was 26, and my first brother, my oldest brother, was 28 when he died. It was like a double blow and I was really not very happy, [laughs] I was grieving in my brother’s apartment. I dedicate the film to my brothers, mainly because of the craziness of my state of mind was the only reason I had no life for five years, and three years of filming alone.

Filmmaker: Did you feel this was particularly challenging for a first feature?

Yaghoobian: Making a film like this, you can easily screw it up. It can maybe sustain itself in a short, but really to make a feature film like this without narration, without teaching people anything, is really difficult. To keep it entertaining and moving from one thing to another, the pace needed to be at a certain level. It was really hard to do that. I sweated over this thing, I really did. I had scientists and aerospace engineer guys come into my apartment – I’d find them on the beach or the street and I’d bring them back. I’d get them to watch the movie – you know, the unlikely audience – and I was happily surprised at how the unexpected audience actually related to the film. A lot of them thought the guys in my movie were actors, they thought they were funny characters. It was wonderful to have that, because that was a big test for me. Now I’m distributing the film, people are saying it’s niche and that only art people will like it, but I think it can transcend that.

Filmmaker: What’s the worst (or weirdest) job you’ve ever had?

Yaghoobian: That’s a bad question! [laughs] I don’t like that question. Making movies. [laughs] No. Actually, honestly, cutting this film. It was horrible. [laughs] It was so hard! Cutting the 250 hours was hell, and doing it all alone was hell. With no help.

Filmmaker: What was your dream job as a kid?

Yaghoobian: I’m so bad with pointed questions! [laughs] I guess I always wanted to make films, because when I was 15 I saw Antonioni’s Blow-Up. I’d miss school because the good movies were at 1 or 2 in the morning. I’d show up late and get my parents to write me a note, or just watch movies all night. I saw Blow-Up and I was fascinated by that whole detective thing. The next day I picked up a camera, and I haven’t stopped since then. That film was awe-inspiring to me, but it wasn’t just me. When that film came out in the 60s, all these guys who wanted to be photographers because they thought that they’d be like photographing these hot girls and having orgies with them.

Filmmaker: Finally, if you could do it all over again, what would you change?

Yaghoobian: I would like to get into surfing. I played soccer for 12 years and was really athletic as a soccer player when I was younger, but I wish I was a surfer. [laughs] I think they’ve got it made. They’re happy and they’re on the water. I just don’t know how to surf. So if I could, I would change it all that way. I missed out before, but now if I could go back that would be the first thing I’d take up.