Back to selection

Back to selection

Debate Club

The Metagame (Culture Edition)

The Metagame (Culture Edition) On a recent Saturday when I had nothing to do, I put out a call to see who was around for a last-minute dinner party.

Result: nine random guests including several journalists, an art critic, one poet, my 22-year-old cousin from Nashville and two game designers.

As will happen when game designers are in the room, we ended up playing.

I’ve mentioned Colleen Macklin and Eric Zimmerman on these pages before. Their work continues to inspire me, and I need to tell you about this game they brought over to my house.

It’s called The Metagame, and it comes from Local No. 12, a game design collective made up of Zimmerman, Macklin and a third designer named John Sharp.

Zimmerman has been designing games professionally for 20 years (and nonprofessionally since he was five); he teaches at the NYU Game Center and recently has been making installation games for museums. Macklin teaches at Parsons, The New School, and runs PETLab, which does rapid prototyping and research for public interest games. Sharp also teaches at Parsons, runs a data-visualization company, and has a Ph.D. in art history.

In other words, these are not the guys working on Medal of Honor or Call of Duty.

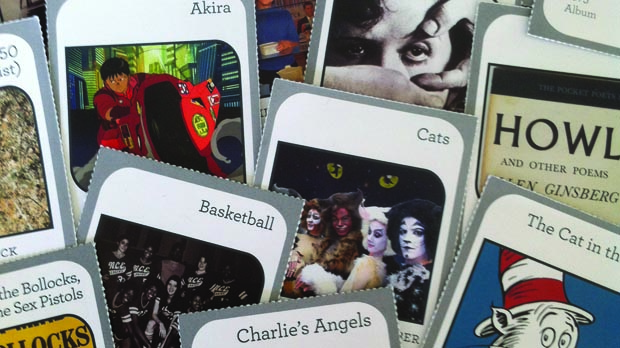

At the 2011 Game Developer’s Conference in San Francisco, Local No. 12 showed up with collectible playing cards. Some had questions on them – Which is more visually beautiful? Which tells a better story? Which is more hardcore? Which is more tragic? Other cards had illustrations of videogames and the maker, date, publisher and platform of the game. World of Goo. Wii Sports. Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? Warcraft II. The basic rules were simple. Three people minimum; at least two players, and one judge. Each player gets five picture cards; the judge presents one of the question cards. Players present the card they think best answers the questions – and then, here’s the really interesting part: Each player has two minutes to make an argument for why she thinks she’s right, and the judge picks the most persuasive argument. There is no right or wrong, no specific win-state, other than having successfully convinced others of one’s own viewpoint. It’s a game of rhetoric, opinion and plain old conversation.

“We were interested in the playfulness of everyday conversation,” Macklin said. “We were just adding a layer of play to what people were already doing, which was talking about games.”

The game was so popular that Zimmerman, Macklin and Sharp launched a Kickstarter campaign in their hotel room at the conference to raise money for a boxed edition. They asked for $10,000. In two days, they got $20,000. At the time, it was one of the most successful campaigns Kickstarter had seen. Since then, they’ve sold about 5,000 decks – at first doing all the packing and shipping out of Zimmerman’s Williamsburg, Brooklyn, apartment, before finally handing it over to Amazon to handle.

So that was The Metagame: The Game Debate Game.

But people kept asking the team, why don’t you make a movie version? Or a music version? So when Tod Lippy called – editor of the ultra-hip art magazine Esopus – they knew just what to do. They made The Metagame (Culture Edition). And this is what they brought over to my house.

Scene: I’ve got some candles going and have just served Bengali fish stew. Macklin whips out the deck. Zimmerman plays as judge. The questions start to fly: Which reminds us more of our inhumanity? Which is more slippery? Which is more derivative? Which feels more dated?

All of us around the table have a handful of cards with images of things like Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion House, Crocs, a Big Mac, Persepolis, Waiting for Godot, Slaughterhouse Five, American Beauty, Jeff Koons’ Rabbit, Jackson Pollock’s Lavender Mist, Duck Soup and The Ramones.

The rules we’re playing by is that the judge picks the least persuasive argument and then the person who delivered it joins him on what becomes, by the end of the game, a judging panel.

(There are an infinite number of ways you can play The Metagame, which was the designers’ intention and part of what makes it so cool. They wanted it to be like a deck of playing cards, able to facilitate a multitude of games, from a quiet parlor game, to a boisterous party activity.)

Things get interesting right away. One of the journalists gets knocked out when he plays Dymaxion House as “feeling most dated” and pouts. When Zimmerman puts out “What would Freud want?” my 22-year-old cousin from Nashville cries, “Who’s Freud?” and then avoids elimination by playing The Bikini and saying nothing.

The art historian takes her full two minutes every time, delivering dissertation-worthy, deadly serious monologues about why Levittown is “a better tool for dictators” and why Charles and Ray Eames’ Lounge Wood Chair is “more pedestrian.” The poet wins by playing “The Macarena” to “Which is more dangerous?” and saying just a few words.

As far as I can tell, the only problem with The Metagame (Culture Edition) is that you can’t get it anywhere except from the edition of Esopus in which it ran – or if you know one of the designers and they bring it over to your house one night at a last-minute dinner party.

The folks at Local No. 12 want to publish it. But the Culture Edition uses photographs rather than illustrations, and they haven’t been able to raise the money to hire the lawyers to secure the rights to all the images yet.

So here’s a card to play while you wait for Local No. 12 to publish: “Which is the biggest, most frustrating impediment to getting the coolest independent art projects off the ground?”

Card to play: money.