Back to selection

Back to selection

GEOFF MARSLETT’S “MARS”|

By Alicia Van Couvering

Geoff Marslett’s Mars is a whimsical rotoscoped space exploration romance starring Mark Duplass, the kind of film whose possible existence may never have occurred to you, but one that you are very glad to have discovered. Marslett, an Austin native and much-lauded teacher of animation at UT Austin, studied mathematics, philosophy, art, science and languages before arriving in Texas to get his degree in narrative filmmaking. Gradually, he began to get interested in animation, taught himself the process and started inventing new techniques for his short films, now numbering over a dozen. Monkey vs. Robot, for instance, has screened at over 25 festivals and on HBO and PBS.

Geoff Marslett’s Mars is a whimsical rotoscoped space exploration romance starring Mark Duplass, the kind of film whose possible existence may never have occurred to you, but one that you are very glad to have discovered. Marslett, an Austin native and much-lauded teacher of animation at UT Austin, studied mathematics, philosophy, art, science and languages before arriving in Texas to get his degree in narrative filmmaking. Gradually, he began to get interested in animation, taught himself the process and started inventing new techniques for his short films, now numbering over a dozen. Monkey vs. Robot, for instance, has screened at over 25 festivals and on HBO and PBS.

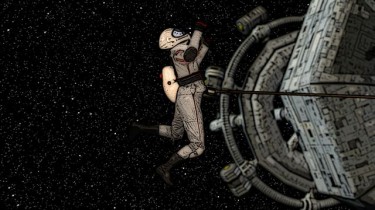

Mars is set in an imagined future when we’ve developed the ability to send astronauts to Mars and communicate with them via video conference, but have adopted a style of clothing and hair reminiscent of what people imagined space looked like in the 1980’s. Zoe Simpson plays Dr. Casey Cook, a gorgeous type-A lead astronaut, partnered with Paul Gordon (who also directed and stars in The Happy Poet), and Mark Duplass (Humpday, The Puffy Chair) is the renegade third astronaut Charlie Brownsville, who discovers at take-off that he was brought along merely as contingency. But as the trio near space, it is Gordon’s character who becomes the third wheel, as Casey Cook and Charlie Brownsville’s flirtation takes off. There’s a certain laid-back Austin vibe to the performances, which is coupled with a vibrant, bouncing image that looks, as Marslett wanted it to, like “a combination between a graphic novel and a hand-drawn photograph.”

Marslett was one of our “25 New Faces of Independent Film” this year and Mars premiered at SXSW this week.

Filmmaker: Is it accurate to describe this as a Rotoscope film?

Geoff Marslett: It’s hard to classify – if people ask me outright to describe the movie I’d say, “Yes, it is a rotoscoped animated film,” but technically it’s a combination of a lot of different animation and processing effects together. I tried to invent a unique visual approach. When I set out to make the film, I wanted to make a romance. When I think about romance, it’s the kind of thing that is at once very approachable and very attractive. and at the same time it’s always a tiny bit out of reach. [Love] is like this thing up on that shelf that you can kind of see clearly, but you cannot quite get your hands around it, and falling in love itself is such a unique experience. The movie is about exploration, and the whole film is an analogy about falling in love, in some ways; why do we explore? You can look at exploration as a bunch of people with guns invading a place, but I prefer to think of it as being about learning about something new – something excites you, and you go to it, and you change it and it changes you. That’s kind of what I think about romance. The moment of falling in love is always a tiny bit out of reach, but at the same time, you’re so close to it. So I actually wanted the visuals to reflect that idea.

Filmmaker: How did you come up with the look of the film? Did you have to write special computer programs for it?

Marslett: A lot of my other animation work is very cartoony – I didn’t want it to be super-cartoony hand-drawn animation, and I didn’t want it to be that removed from reality. I wanted to be able to recognize faces, to recognize their expressions. But at the same time I didn’t want it to feel like you were fully there, I wanted that separation, something I could best describe as somewhere between a graphic novel and hand-drawn photograph. The [animation] program that I wrote, I first used on a short called Bubblecraft and it looks similar to Mars. [Creating it] was a unique opportunity. Tim DeLaughter from the band The Polyphonic Spree has a label and they called me up looking for recommendations for a filmmaker that could make a small-budget music video for a new band they were promoting. I gave them some names, slept on it and then called them back the next morning and said, “Hey, wait, I cannot make this video for the budget you’ve got, but I might make it anyway if you let me test out this program on it.” That helped pay for my experiment and writing the program, which turned into Bubblecraft. I was kind of inspired by Waking Life and A Scanner Darkly – I know Bob Sabiston personally and he’s a great guy, and I was always inspired by how he just wrote the programs to get the look he wanted. But I didn’t want anything quite as dreamy as that. I wanted something that was a little more anchored, in some ways aesthetically similar to Sin City, but not as realistic. Oddly, my two visual inspirations also came from Austin. So I wrote this program, and I am not a very good programmer — what it essentially did was convert the actual colors from actors shot on green screen and turned them into vectors, then processed them and did some other things to them. It allowed me to use the real colors instead of hand-coloring my animation. I took those real colors and went back and added the major line work for things like eyes, noses; outlines where I knew I needed a line that wouldn’t dance, that would be very stable. The other thing my program did was to help me apply a shadow pass on it, which was made up of little green dots. And then we composited all three of these things together.

Filmmaker: I don’t know anything about animation, can you explain how that’s different from traditional rotoscoping?

Geoff Marslett: In traditional rotoscope animation you would hand-trace the whole event, you film something, get out your pencils and trace it, or bring out your computer and trace everything, then color it back in so that the whole image is rotoscoped. But my characters are partially hand-traced, and partially made up of an automated system of actually processing the colors, and a third process where we create stuff that wasn’t in the original image. Ours is like, you take the main features and layer it over something that is actually a processed version of what you shot as your original image. The entire world we put the characters in, in contrast to Walking Life or A Scanner Darkly where they actually shot actors in locations or sets, is completely invented. We had no locations or sets. When we shot the actors there were no props; they never picked anything up — the walls were green, and anything they touched was just a green box. We used a combination of 3-D programs to do backgrounds and hand-drawn backgrounds. The buggy that they drive around in on Mars, for example, we created completely in a 3-D program, as opposed to rotoscoping, where one would have actually shot them in a buggy and then drawn that. Then took those in and rotoscoped over those and then composited the whole thing together. So is it Rotoscoping? I am going to go with ‘Yes, but you have the little after effects in there too.’ I hope when people watch they’re like, “I don’t know exactly what I am watching;” that was the ultimate goal.

Filmmaker: How long did it take to make this?

Marslett: I started writing the script in June of 2007, we shot in September of 2007, and basically finished our first pass of the edit in February of 2008 and then spent until January of 2010 animating. If this had been a live-action film we probably would have finished a couple years earlier. It took a solid extra couple years worth of animating to finish it.

Filmmaker: Wow. So you edited the film completely, then started animating?

Marslett: Yeah. I edited it with a guy David Fabelo, and I would say about 75 per cent of the editing was done before we animated any of it. We just did it based on the live-action footage.

Filmmaker: What inspired you to write the script? You spoke about wanting to make a romance earlier, how did you arrive at setting it on an expedition to Mars in the not-too-distant future?

Marslett: t’s kind of interesting because I kind of knew I was going to write a romantic piece even before I knew I was going to set it on Mars. And I got the [idea for that metaphor] and then I was like, “Okay, now what’s the visual I want to work with?” and as I got further into the visual process I was like, “Great, this opens me up because I don’t have to put them in real locations, they really can be anywhere.” Because I’ve always really liked that idea of exploring and falling in love — when you meet someone new and you’re falling for them, it’s so neat to not know about them, and as you learn stuff about them, it changes things about you. A new person is like a new frontier. It’s like, what’s more exciting than a first date where you go to another planet, you know?

Filmmaker: How did you cast the film?

Marslett: I feel like I got really lucky on casting. You know I also teach at the University of Texas, and one of the things I tell my students is that a bad script can at least be made watchable by really good actors; a really phenomenal script can be rendered unwatchable by bad acting. Basically, it’s really important to have good acting. While the visuals are a selling point to the film, certainly without a good story and really solid performances the film won’t work. So I spent a good amount of that pre-production time just cold-calling actors. Just calling up saying, I am this guy you’ve never heard of that lives in Texas and has never made another feature film and I want you to take a chance and come out here, I am going to pay you chump change and you’re going to be in my movie – surprisingly, a lot of people didn’t go for it. I think where I got lucky was that I had made Bubble Craft and a couple of little pieces of sample footage, and I put those up on a little password-protected website and when I got a hold of a manager or an agent of one of the actors that I wanted to work with, I’d say, ‘I know this sounds like a crazy idea but just go to this website, watch this clip, the thing that we are making is at least a little bit different from everything else.’ If they liked it, then I could get a script in their hands. And if they liked the script, then we were in business. With Mark [Duplass], we have some mutual friends, but certainly I had never met him before shooting Mars. When we first started this, the only film I think he had out at this point was Puffy Chair, this was way before all of the other films and TV shows he’s known for now had been made. We were talking to some higher profile actors for that role, but I remember getting off the phone with Mark and being like, “Okay, he completely gets this character better than anyone else I’ve talked to.” So we kind of went out on a limb, and I feel like that really paid off. I feel like I wasn’t the only person that noticed that he’s really talented. I’ve also enjoyed working with people who aren’t really actors. The “villain,” the NASA commander, is Howe Gelb, who is really known as a musician. He also wrote the soundtrack and performed most of it for me. I’d worked with him on my thesis film ten years before because I was always a fan of his bands, I had cold-called him when I was in grad school to be in my thesis film. And we have James Kochalka, who is really a comic book artist and a musician first, playing an entertainment reporter. Kinky Friedman of course, and even Don Hertzfeldt, an Academy Award-nominated animator, has a small role. I tried to fill the movie with fun people like that. The third astronaut, Captain Hank, he’s this guy Paul Gordon who directed a film that’s going to be premiering at SXSW as well called Happy Poet. So it was a really eclectic bunch. I just tried to get people who I thought would be charismatic.

Marslett: I feel like I got really lucky on casting. You know I also teach at the University of Texas, and one of the things I tell my students is that a bad script can at least be made watchable by really good actors; a really phenomenal script can be rendered unwatchable by bad acting. Basically, it’s really important to have good acting. While the visuals are a selling point to the film, certainly without a good story and really solid performances the film won’t work. So I spent a good amount of that pre-production time just cold-calling actors. Just calling up saying, I am this guy you’ve never heard of that lives in Texas and has never made another feature film and I want you to take a chance and come out here, I am going to pay you chump change and you’re going to be in my movie – surprisingly, a lot of people didn’t go for it. I think where I got lucky was that I had made Bubble Craft and a couple of little pieces of sample footage, and I put those up on a little password-protected website and when I got a hold of a manager or an agent of one of the actors that I wanted to work with, I’d say, ‘I know this sounds like a crazy idea but just go to this website, watch this clip, the thing that we are making is at least a little bit different from everything else.’ If they liked it, then I could get a script in their hands. And if they liked the script, then we were in business. With Mark [Duplass], we have some mutual friends, but certainly I had never met him before shooting Mars. When we first started this, the only film I think he had out at this point was Puffy Chair, this was way before all of the other films and TV shows he’s known for now had been made. We were talking to some higher profile actors for that role, but I remember getting off the phone with Mark and being like, “Okay, he completely gets this character better than anyone else I’ve talked to.” So we kind of went out on a limb, and I feel like that really paid off. I feel like I wasn’t the only person that noticed that he’s really talented. I’ve also enjoyed working with people who aren’t really actors. The “villain,” the NASA commander, is Howe Gelb, who is really known as a musician. He also wrote the soundtrack and performed most of it for me. I’d worked with him on my thesis film ten years before because I was always a fan of his bands, I had cold-called him when I was in grad school to be in my thesis film. And we have James Kochalka, who is really a comic book artist and a musician first, playing an entertainment reporter. Kinky Friedman of course, and even Don Hertzfeldt, an Academy Award-nominated animator, has a small role. I tried to fill the movie with fun people like that. The third astronaut, Captain Hank, he’s this guy Paul Gordon who directed a film that’s going to be premiering at SXSW as well called Happy Poet. So it was a really eclectic bunch. I just tried to get people who I thought would be charismatic.

Filmmaker: How did the film change from when you began to the finished product?

Marslett: That’s actually a good question. If I had to describe how we made this film, it’s that we made it up as we went along. Most of my animation skills are self-taught. So it felt sort of natural, just like, “I have an idea in my head of what this should look like, let’s come up with a way we can do this,” and then making that up. When I’m animating without actors, I can just sit down in front of the paper or computer and just make it however I want it to be. Putting actors into this situation, you’re on a greenscreen stage and you’re envisioning this world that no one else can see, and then you need to convince those actors that this world is there, too. It’s probably even tougher on them than it is on me as a director. For instance, we only had one green wall, so if I wanted to do a 360 degree camera move, we actually built giant lazy susan and had them stand on that and I had grips rotate the floor underneath the actor while the camera stood still. I had to say to them, “Imagine you’re standing still and the camera is moving around, but keep your eye line here.” It’s a weird way to make a film. But it’s fun. And they started to get into it.

Filmmaker: How many people actually animated the film?

Marslett: The best answer is not nearly enough. If you look at any animated film they have this long list of people. Basically six of us animated it, with some help from some interns. It was really a lot of work. We didn’t have the budget that you really need to do this. There were three or four of us that spent the better part of a year on it. I would get off work from UT, say on Wednesday. I would go into the office Wednesday evening and animate and I would stay there until Monday morning. You would just take a nap on the floor when you were tired. We would work 24-hours a day, seven days a week. I was in there on Thanksgiving, I was there on my birthday, Christmas, when Obama was getting elected, etc. I was constantly in that room. And there were several other people in there with me. So when you read those credits, you’re like, “Wow, it doesn’t seem like enough people have animated this.” Part of that is because there really wasn’t. I will owe them forever.