Back to selection

Back to selection

Making HENRi: A Low-Budget Sci-fi Short Film Odyssey

A little over three years ago, I decided I wanted to make a sci-fi short film about a robot trying to become human. My idea was to combine live action with miniatures and rod-puppetry – despite having no previous experience with special effects. Initial reactions from family, friends, and collaborators were of the “Are you insane?” variety – perhaps rightfully so. It was at that point I knew I had to make the film.

What followed was an odd combination of luck, coincidence, and disaster – three ingredients that are rarely talked about, yet I’m convinced are completely inseparable from the process of making a movie. I’d add in creativity, hard work, and collaboration, but those go without saying. This story is about the other stuff.

HENRi was born out of my fascination with the science fiction films of the 70s and 80s. I probably owe more than a little credit to the influential work of Isaac Asimov and Philip K. Dick as well. I love it when sci-fi subverts genre conventions to tell unique stories about the human condition. My particular interest for this film was memory and its intrinsic relationship with consciousness. I also wanted a robot of my very own.

Early on in the process I turned to Kickstarter to help raise funds for the project. Focusing on the unique aspects of the production – the story, the heavy use of in-camera effects, and miniatures – we exceeded our fundraising goal by almost $7,000. The show of support from complete strangers was incredible and unexpected. Suddenly, we had funding, a community, and a green light.

My approach was to make the film as professional looking as possible with the small budget that we had. I knew I couldn’t do that alone, so I crossed my fingers and blind-contacted some of the best in the business. With my passion for the project and some definite luck, I was able to bring on Tim Angulo as director of photography and Jefferson Richard as producer. Tim’s work includes shooting the miniatures for Spider-Man, The Dark Knight, and Inception, among many others. He adapted to our microbudget, do-it-yourself attitude, and was an integral part of getting the film made. Jefferson was my producer, but more importantly, my mentor – coincidentally, Orson Welles was his. Jefferson wrangled an uncharacteristically complex production for a short film, and kept things moving with next to no money. Needless to say, I was in good hands.

Having Keir Dullea and Margot Kidder join the project was another crucial element of the film’s success. I’m often asked at festival Q&As how we were able to get Keir and Margot to star in the film, and the answers are disappointingly simple. Our casting director happened to be a college roommate of Margot’s. To get Keir, we just asked. One of the many things this film taught me is to always go for your top choices, no matter how out there. The worst that can happen is someone says no. I am very humbled by the fact that through Keir Dullea, my little sci-fi short film shares a connection to 2001: A Space Odyssey – something that would have never happened had I not simply asked.

We shot the majority of the film in a warehouse in Salt Lake City, Utah, working with a local Hollywood effects veteran. The concept of using quarter-scale miniatures to create HENRi was initially born out of necessity – we just didn’t have the budget to build full-size sets – but I also wanted to use the technique because that’s how the classics were made. Seeing everything come together was my favorite part of the process – I grew up reading Cinefex and building models, so I loved being able to pitch in and help out where I could. We built the entire world of the film piece by kit-bashed piece in a little over a month.

The honeymoon was short.

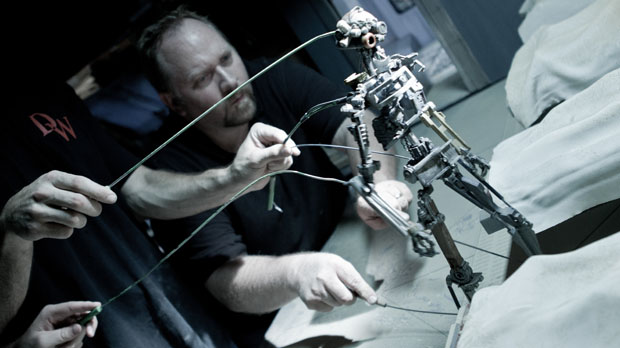

Working with miniatures and puppets is an extremely time-consuming process, especially when you add motion control into the mix. It’s often frustrating, and in many ways very limiting. Henri, our robot main character, was an 18-inch rod-puppet – which is essentially an articulated doll. Rods were attached to his legs, arms, torso and head; this allowed three or four people working in tandem to manipulate his movement. We would shoot Henri first, usually averaging around 20 takes before time restraints forced us to move on. We would then shoot a clean background plate, giving us the ability to digitally erase the rods in post-production. This process typically took anywhere from three to six hours, and was repeated for every shot featuring the robot – over 60 in all!

Unfortunately, Henri didn’t perform as well as we had hoped. That’s a polite way of saying the rod-puppet didn’t really work. In the end, only about 15% of the Henri shots were usable. Suddenly, the clean plates became much more important. I was left with no choice but to finish the film as planned, knowing we would need to go back and create a fully digital character in post-production – an idea that terrified me. Going over budget was all but a certainty now, and even more worrisome was the prospect of creating a photo-real robot. If Henri wasn’t a believable character, the film would be dead on arrival. It was a disaster, and I thought we were sunk.

Fortunately, the artists at Blufire Studios in Utah believed in the project and stepped in to handle the complicated effects work that was necessary to complete the film. This unforeseen work in post had a bright silver lining – the animators needed motion reference to create the digital Henri, so we ended up shooting video reference footage of every shot with an actor standing in for the robot. I was thrilled – it gave me a chance to direct a performance and breathe some much-needed human life into the character, giving Henri something the rod-puppet couldn’t – and it never would have happened without everything going wrong.

In the end, it took two years from the day we shot to the day we finished post-production. It was not a smooth process, and there were times when giving up looked like the sane option. I went through periods where I openly hated everything about the project. For several months after finishing the film, just looking at the Henri puppet would make me physically ill – now he’s the wallpaper on my phone. Go figure. I’m proud of the work we did, and I’m excited to finally release the short to the general public. With a little luck and despite disaster, HENRi lives.

You can learn more about the film at www.henrithefilm.com