Back to selection

Back to selection

Life’s Compass: Talena Sanders on Liahona

Liahona

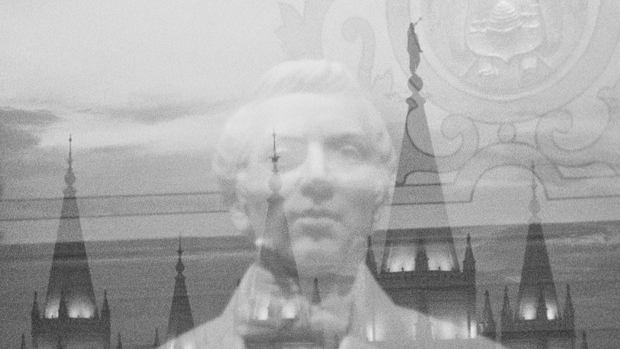

Liahona Liahona begins with distant figures walking silently through a field. It is nighttime, and both the sky and the ground seem to sparkle. The people move slowly while wearing glittering and flickeringly feathered costumes that, from a distance, make them appear to be extraterrestrial. Within the scope of modern American culture, perhaps they are: they’re members of the Church of Latter-Day Saints, known more commonly as Mormons.

This opening sequence of American filmmaker Talena Sanders’s 2013 debut feature — which will screen in September at Brazil’s Indie Festival, following sessions at FIDMarseille and at last year’s New York Film Festival — takes place in Salt Lake City at the annual Mormon Miracle Pageant. The walking figures are local youth acting out the conversion of indigenous peoples to their faith. Liahona follows this sequence of them with an impressionistic portrait of Mormon life in the United States, often seemingly rendered as though from an outsider’s point of view.

“What is a Mormon? What do they believe?” a male narrator soon asks. “What makes them so distinctively different? What do you know about the Mormons?” This film by Sanders — a thirty year-old secular artist who grew up in the Church — continues to ask such questions, without giving direct answers.

The man’s voice comes from a found audio recording, as do the sounds of choir organs and spiritual hymns that resonate throughout the film’s soundtrack. Many of the images accompanying them arrive from found footage. Some are taken from Church-commissioned promotional films detailing the journey taken by the Church’s founder Joseph Smith, a self-proclaimed prophet who wrote the Book of Mormon in 1830 and who left the Church in his followers’ hands following his death by mob violence in 1844. Others come from home movies made by Church members and show people preaching and receiving God’s word, or simpler, more basic images of family members greeting each other. All are displayed for us as though they had been found on an archeological dig.

The images stimulate curiosity by seemingly calling out to viewers. They draw us towards the human beings within them, whose expressions register as calm, hopeful, and even happy. As we sift through the fragments, we might feel ourselves drawing closer to those who originally participated in their making. Liahona’s myriad depopulated shots of rocks and sand give the sense that we might be looking outwards in the same direction as them, and seeing what they see.

Sanders interpolates her found sounds and sights with original 16mm Bolex footage of landscapes and town streets, sometimes containing people posed as though waiting for something left up to us to fill in. Liahona encourages us to look not at costumes, but at faces, and bring ourselves to people whose lives could easily be ours. It does so even while shifting gradually from a study of Mormon life in general to one particular life, as Sanders’ own voice enters the film’s soundtrack to recite texts, sing songs, and ask her Mormon parents questions about their Church experiences.

Liahona provisionally concludes a series of films and expanded cinema installations that Sanders has made in exploration of Mormonism. In some, such as 2013’s The Relief Mining Co., she interviews Church followers about their beliefs; in others, such as 2012’s Tokens and Penalties 1, she herself appears enacting Church rituals. By the end of Liahona, we understand that she has set aside the Church’s teachings in favor of seeking to learn the world’s ways for herself. We might also wonder whether someone who has followed a faith can ever truly leave it behind.

Filmmaker: What does “Liahona” mean?

Sanders: The Liahona was a compass used by an early Mormon tribe to navigate from Israel to North America. This directional tool transmitted messages from God. The compass lost its power, though, if you lost your faith. Joseph Smith claimed to have access to the Liahona while he was translating the Book of Mormon, but he showed the Book to the wrong person afterwards and God took the Liahona from him.

I began thinking about my film Liahona as a way to triangulate Mormon culture and history, the role of Mormonism in contemporary American society, and my background. I wanted to tell my story within a larger context. When I lost my faith at age 20, I lost a guide to life. I had had a path laid out for me that I chose to abandon, and I was suddenly in a different world that I needed to navigate without the tools on which I had always relied.

Filmmaker: Why did you lose your faith?

Sanders: For several reasons. My father grew up in the Church, and my mother converted after marrying him. (I’m fourth-generation Mormon from my father’s side.) Many of the women in my mom’s family had gone through divorces and bad relationships and had been single mothers, and they always told me, “Get an education. Provide for yourself. Never believe that you can rely on a man.” The Church taught me the opposite — I should forego university in order to raise a family, and my husband would provide for us. In light of my family members’ experiences, its messages seemed like fantasy.

I came to believe that I couldn’t feel fulfilled as someone who was primarily a wife and mother. That life wasn’t for me, and I grew to understand that it couldn’t be for a number of people I loved. I had gay friends in high school, and I struggled to remain in an organization that taught that they were living in sin.

Filmmaker: How did you seek out moving image work?

Sanders: I took an installation class in college. At the time I was working towards a degree in fashion design, but with that one course I was done making things were meant to be functional. Every idea I came up with had a moving image basis. I conceived my work for a gallery context, and when I moved to New York after school ended I worked with a collective, creating live performance works with looping pieces in collaboration with dancers and audio artists.

I started my moving image practice while I was still officially a member of the Church, but the period of overlap was very short. I do believe that I moved from one structured form of devotion to another. The amount of time I spent involved in Church activities was more than replaced by art-making. I wanted to work all the time, and I still do. Even years after leaving the Church, the Mormon habit of industriousness has remained important to who I am.

The American filmmaker David Gatten — a professor, mentor and friend of mine — helped me begin thinking about making work for a theatrical context, in which the audience would be more likely to stay for the duration of an entire filmed experience and feel its meaning grow over time. I went from occupying large spaces to condensing my ideas into single screens. I wanted to work with expanding and collapsing a sense of time rather than one of physical space.

With that said, atmosphere stayed vital to me as I moved from installation art to cinema. The experience of being inside a thick atmosphere is what Liahona is about. Although Mormonism is a young religion, Mormon culture is vast. Growing up Mormon feels all encompassing. Admittedly, if you’re in Utah, you have some freedom to practice what you might call “Cafeteria Mormonism,” and pick and choose a bit which rules to obey; but when you grow up like I did, in a rural Kentucky town with only one other Mormon family, you have to buy all the way into the faith. It becomes a huge part of you.

I wanted to combine a number of different materials — 16mm Bolex footage that I shot on a trip to Utah in concert with found footage and found audio — in order to build a sense of being swept up inside the culture. I knew that some of the symbology in Liahona would be inaccessible to people lacking knowledge of Mormon doctrine, but I hoped that the film would resonate for any viewer who had tried to find himself or herself within a large institution.

Filmmaker: What story does Liahona tell?

Sanders: I have thought about the film in a narrative way, but what that narrative is, exactly, is something I find hard to talk about. This is partly because my current relationship with the Church is very complicated, as are those of pretty much everyone I’ve talked to who has left it. I can begin by saying that the film presents some aspects of the Church that I wanted to highlight — landmark Mormon life experiences such as the Mormon mission, or temple marriage. There are also some elements that you can find in first-person accounts from Church history that don’t have logical explanations, and that seem like genuinely miraculous happenings. The Church doesn’t like to highlight its mystical elements within its self-presentation, but now that I’m outside I find them moving and fascinating.

At the same time, I wanted to convey external resistance to Mormon beliefs. Something that I have always experienced is the sensation of Mormonism being regarded as a cultural Other, even within the United States. When I tell someone that I was born Mormon, the person often reacts with titillation like I was an exotic creature. “Tell me about the weird things,” he or she will say. “Tell me about the underwear.” Strangers often feel Mormonism to be mysterious and inaccessible, and I wanted to explore their feelings in the film.

Liahona therefore features two narratives butting up against each other throughout its first section. One shows the development of an interior voice outwards, reflecting ways in which the Church tries to project its image to the world. The other tracks the progression of a documentary voice made up of sources outside the Church that look toward it and comment on it.

My voice overtly enters the film after a period of tension between them. When it arrives, the viewer discovers the filmmaker’s relation to the Mormon Church. I am simultaneously an insider and an outsider. My story lies somewhat in opposition to the institution’s, but not entirely.

Filmmaker: How did you gather the film’s material—the found footage, as well as the footage you shot?

Sanders: The found footage mostly came from online. I got into the habit of scouring eBay to see what might come up. Many of the audio materials came from great Church-owned thrift stores called Deseret Industries where my Utah-based friend Kate Schlauch bought me records and cassette tapes.

Kate basically acted as my Sherpa while I was in Utah. Sometimes I had someone come with me while I was shooting in order to handle sound, and often I brought a friend with me just so that I wouldn’t be alone. It’s unusual for a young woman to be by herself at Mormon events, especially if she’s dressed in the modest Mormon fashion, like I often was. Kate and I would attempt to pass as Mormon ladies so that I could move through events and landmarks with my camera. There’s a general discomfort with outside voices telling Mormon stories, but for as long as I looked like a Mormon lady with a funny love for antique cameras, it was easy for me to record footage.

The Mormon Church illuminates some things for its followers and hides others from them. Visually, I wanted to work with extremes of the light spectrum. In Utah you’re at a high altitude, fairly close to the sun, and the light seems volatile. I could start shooting, and then during the course of a shot the light would change. In the past, when I’ve worked with still photo and film and video, I’ve always shot in darker registers, so this was a challenge for me.

When you’re in northern Utah, with its snow-capped ranges and salt flats, you sometimes feel like you’re on the moon. In southern Utah it’s more of a Martian landscape with red rock desert. The land reflects Mormonism’s cosmology. It’s easy to feel otherworldly there.

Utah’s landscape is an epic stage for the foundation of an epic religion. Landscape has always figured into Mormon filmmaking, a fact that I didn’t appreciate until after I was done with Liahona’s shoot. I realized the extent to which my experiences of seeing Mormon films have informed my own cinema, as well as my sense of how people can experience the Divine. I wasn’t good at reading the Book of Mormon when I was young. Most of my experience of doctrine came from watching Mormon films in church and at youth events.

Filmmaker: What were they like?

Sanders: They’re professional productions. The Church has a film lot in Provo and an online talent database for members to sign up to act in films. There are many people out here in the Mormon film industry. A lot of the films that I grew up watching were made by students from Brigham Young University’s Film program. I’ve definitely drawn on those films’ usages of landscape as refrain. I’ve also borrowed from the ways in which they use superimpositions, which are typically employed when showing supernatural events. The way that I capture light with very strange long lens flares is something I’ve seen in Mormon films. I am using some of the language of Mormon cinema in order to explore how Mormon storytellers present their work to audiences.

I only understood that I was doing this after I came back from Utah, though. A lot of what I had done had come subconsciously and with mistakes whose results proved more exciting than what I had intended to capture. Liahona’s slow-motion footage offers one example. I first began working in cinema with digital camcorders, and so a lot of the metering and light adjustments that 16mm Bolex work requires was new to me. I would be shooting without understanding that I needed to change my exposure, but I could see in the flash frames between each shot that the metering mistakes were making the footage more conceptually in line with my intentions.

I can immediately think about Liahona’s Mormon Miracle Pageant sequence. The Mormon Church puts on outdoor summer pageants as a missionary tool. They’re quite large spectacles. They have pyrotechnics. They take place at night in fields where ten thousand folding chairs have been set up. Local high school kids appear in elaborately glitzy Native American costumes, playing indigenous people that the Book of Mormon says that Christ visited post-Resurrection, and walk through the crowd taking peoples’ contact information. It would be easy to present this kind of scene in a sensationalistic way, but in my film, it unfolds through underexposed slow-motion footage, making the action seem like it’s taking place within a field of stars.

Of course the film also reflects my problems with the Church. Throughout its first half, the criticism is pretty light-handed, and then at the midpoint I present a series of title cards stating statistics about social problems in Utah, such as the rampant abuses of painkillers and prescription drugs and the state being home to America’s highest concentration of online pornography consumption (despite the Mormon Church’s vilification of porn). It made sense to me that such problems would emerge in a highly restrictive culture. By presenting the statistics, I am being forward about my position. I am also laying myself bare for viewers, who will get to know me more afterwards.

Filmmaker: How did you shape your material?

Sanders: In general, I spend a good amount of time in the editing room playing with a few images, until at some point something will break for me and I’ll lay out swaths of film during the night. I then retain the basic structure and ideas from an initial rough cut while perfecting, building, and condensing in order to pack as much as I can into spaces.

I created several of Liahona’s episodes by concentrating on images first and sound afterwards. Sometime I went with a more vacated image in the service of sound. There is a moment in which a song by Rosalie Sorrels, “Don’t Marry the Mormon Boys,” plays over an image of a cactus that has toilet paper stuck to it as though the paper were a veil. There is another moment, towards the end of the film, in which you hear me trying and failing to sing a Mormon hymn over the gray sight of rock formations in Zion National Park. Suddenly, the landscape turns to full Ektachrome color, and you catch the sounds of a group of men effortlessly singing the same song.

Filmmaker: How do you feel that Liahona’s tensions are resolved?

Sanders: I don’t know that they are, but I can tell you that I am trying not to make more Mormon work right now. I don’t want to make Mormon-themed projects exclusively. I have some ideas that I am developing for shorts and documentaries on other subjects that are personally significant to me, and I would like to let Liahona be an exorcism for a while. Just for a while, though — not forever. The Mormon well is very deep, and I’ll no doubt return to explore again someday.

I wanted to leave a lot open at the film’s close, reflecting the complicated nature of a relationship with a religion. For me the film’s ending speaks to the problem of wanting to break away from a faith while seeing its virtues. You hear me reading my Church resignation letter, which is written in a cold administrative voice; then you hear an archival audio recording of a story about a man named William Daniels who converted to Mormonism in the 1840s. Daniels witnessed the men who had killed Joseph Smith being paralyzed by an intense light from the heavens, and became a Mormon afterwards for reasons whose truth we don’t know.

His entrance, following my exit, turns the film around. To end with another story of faith revives questions.

Information about Liahona and Talena Sanders’s other work can be found at the artist’s website, talenasanders.com.

Thanks to Mark McElhatten, a great film programmer, for research help.

Aaron Cutler keeps a film criticism website, The Moviegoer, at http://aaroncutler.tumblr.com.