Back to selection

Back to selection

Blow-Up, Being There and The Last Tycoon: Jim Hemphill’s Home Video Recommendations

Blow-Up

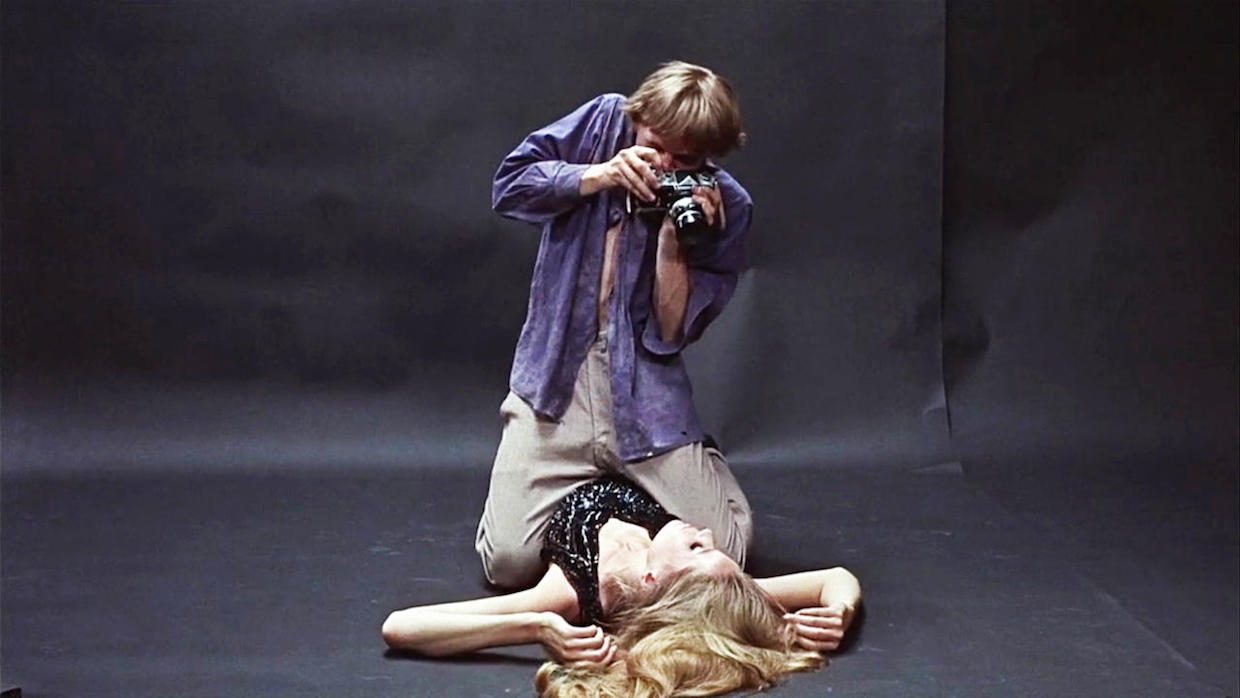

Blow-Up Two very different but equally essential classics find their way to Blu-ray and DVD this week courtesy of the Criterion Collection, which has issued exemplary special editions of Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966) and Hal Ashby’s Being There (1979). The Antonioni film, in which a fashion photographer finds evidence of a murder in one of his stills, heavily influenced later American political thrillers like The Conversation and Blow Out in spite of the fact that Blow-Up itself is less a mystery than an anthropological document of swinging ’60s London. It was Antonioni’s first film outside his home country after L’avventura, La Notte, L’Eclisse and Red Desert made him an international art house superstar, and shooting in England seems to have both reenergized him and added even more emotional detachment to his work. It’s an almost purely intellectual, analytical film, heavily concerned with art and photographic theory as well as the rituals and fashions of the London denizens it follows. Yet from this cerebral approach subtle emotional content does emerge, as tantalizing clues about the personal life of the photographer emerge in the dialogue alongside visual cues informing us of what exactly Antonioni is up to: another of his narrative experiments in which substance exists in the ellipses and architecture reflects and comments upon character. While the milieu makes Blow-Up seem at first glance to be more superficial than the masterpieces that preceded it in Antonioni’s filmography, it’s every bit as layered and profound, and grows more so on repeat viewings. The Criterion edition of the movie contains hours of special features that beautifully explicate the film’s place in the history of visual arts and delve deeply into Antonioni’s process.

Being There is a more immediately accessible but no less complex snapshot of its era — and perhaps a prescient predictor of the current one. Based on Jerzy Kosinski’s novel, it tells the story of Chance (Peter Sellers), a simple-minded gardener who has learned everything he knows from television and becomes mistaken for a political and economic genius by the Washington, D.C. elite. While this idea might sound like something that would lend itself to clumsily obvious satire, in director Hal Ashby’s hands it becomes a far more beautiful, empathetic, and subtly savage piece; Ashby and screenwriter Robert C. Jones (uncredited but, by all reliable accounts, the sole author of the adaptation) avoid clichés and easy targets at every juncture, creating instead a poignant and hilarious examination of the simultaneously corrosive and addictive nature of the mass media, and of the ways in which we either accept or reject the information it feeds us – often choosing wrongly. Sellers gives the performance of his career as Chance, and Ashby showcases him with a beautiful but unadorned visual style in which cinematographer Caleb Deschanel takes his cues from Gordon Willis’ work on the Godfather films to tell the story in a series of exquisitely composed, delicately lit tableaux. The simplicity mirrors Chance’s own view of the world, yet it’s a deceptive simplicity, an accessible gateway to an abundance of sophisticated ideas about television, politics, culture, and identity. As with Blow-Up, the Criterion supplements are generous — a making-of documentary containing interviews with Deschanel, Jones, and others is particularly enlightening.

The Godfather informs another home video option I’d like to recommend this week, writer-director Billy Ray’s superb television adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Last Tycoon for Amazon. Right now the pilot episode is streaming on Amazon Prime, with the rest of the series set to drop later this year, and it’s an hour-long jewel in which classical aesthetics and modern digital technology intersect with dazzling results. The series takes place in 1930s Hollywood at a time when the industry is being rocked by aesthetic, economic and labor issues as well as foreign policy concerns, and Ray deftly juggles the complicated issues and period details with concision and clarity — much like the films of the 1930s to which the series pays homage. Using his lead characters of an Irving Thalberg-esque boy wonder producer (an excellent Matt Bomer) and a good-natured but ruthlessly pragmatic studio head (an equally excellent Kelsey Grammer) as conduits for his preoccupations, Ray uses Fitzgerald’s unfinished novel as a jumping off point for an expansive study of Hollywood in transition that works as both a thoroughly entertaining self-contained drama and as a provocative commentary that one can contrast and compare with the present-day industry. The sophistication of Ray’s writing is matched by the elegance of his visual style, which merges aspects of Coppola and Lumet’s 1970s output – particularly when it comes to their formal compositions and lighting that emphasizes shifting power dynamics among the characters – with the pop pleasures of Singin’ In the Rain and the style of the 1930s musicals and melodramas that the series so lovingly recreates. Cinematographer Danny Moder gives The Last Tycoon the depth and texture of a high-end theatrical feature, shooting at 4K and lighting frames within frames with details that seem to extend into infinity – I’ve rarely seen television so that’s so pleasing to the eye, yet there’s nothing intrusive or self-conscious about Moder’s technique. It’s so perfectly expressive of the relationships and ideas at the core of Ray’s script that the gorgeous flourishes never feel like showing off; they’re every bit as organic as what one finds in Willis and Deschanel’s best work.

Jim Hemphill is the writer and director of the award-winning film The Trouble with the Truth, which is currently available on DVD, iTunes, and Amazon Prime. His website is www.jimhemphillfilms.com.