Back to selection

Back to selection

Filmmaking and Filmmaker: Advice for First-Timers from a Journalist-Turned-Director

After shipping the Fall 2006 issue of Filmmaker, where I had been the managing editor for nearly four years, I moved to Los Angeles to start my career as a movie director, the only thing I had ever wanted to do with myself. I had just turned 30, and I was behind schedule.

At the time, my expectations didn’t seem so delusional. To begin with, I had found the story I needed to tell, something in a voice that was uniquely my own, and I wasn’t alone in my enthusiasm. I had a top agency and management company behind me, along with some blue-chip indie producers. If all went according to what I was being told, we’d be in production within a year, two max. And then it all started to fall apart, in super slow motion, for the next eight years, until it didn’t. There is a happy ending to this chapter of my life story — it just ended up being one long-ass chapter.

But first: a brief recap of my years at Filmmaker, the quarterly indie film bible I had devoured religiously since college. It happened thanks to the strange kismet of the Sundance Film Festival shuttle service. It was 2003. By then, I had legit film journalism credentials, including gigs as a staff writer at Variety and as the senior editor at Indiewire. But at the moment I was covering the festival for a one-off freelance assignment. I was broke, frustrated and sorely in need of a gig that gave me some sense of forward motion. Even if I wasn’t a director yet, I still needed at least a steady paycheck and some form of self-expression.

Sitting next to me on a schlep from the Eccles to the Egyptian was Steve Gallagher, a tall, affable guy from the Bronx with a shock of red hair who looked like he knew his way around Sundance. We struck up a conversation. He told me he was the publisher of Filmmaker and that they needed a new managing editor — immediately.

Less than a week later, I started work in Filmmaker’s dingy grey office opposite the Bryant Park library in Midtown. $30k a year, no benefits, no chance of a raise. It was madness in all the right kind of ways.

The day-to-day office staff was minimal, to say the least. Just me, Steve and André Salas, our subscriptions manager and in-house go-to for all things Fassbinder, 1970s cult Euro horror and J-pop.

The editorial team consisted of me, senior editor Peter Bowen (a brilliant and wonderful man who moonlit for us while holding a full-time job at the Sundance Channel) and, of course, Scott Macaulay, Filmmaker’s co-founder and editor-in-chief and one of the most fearless producers in the business.

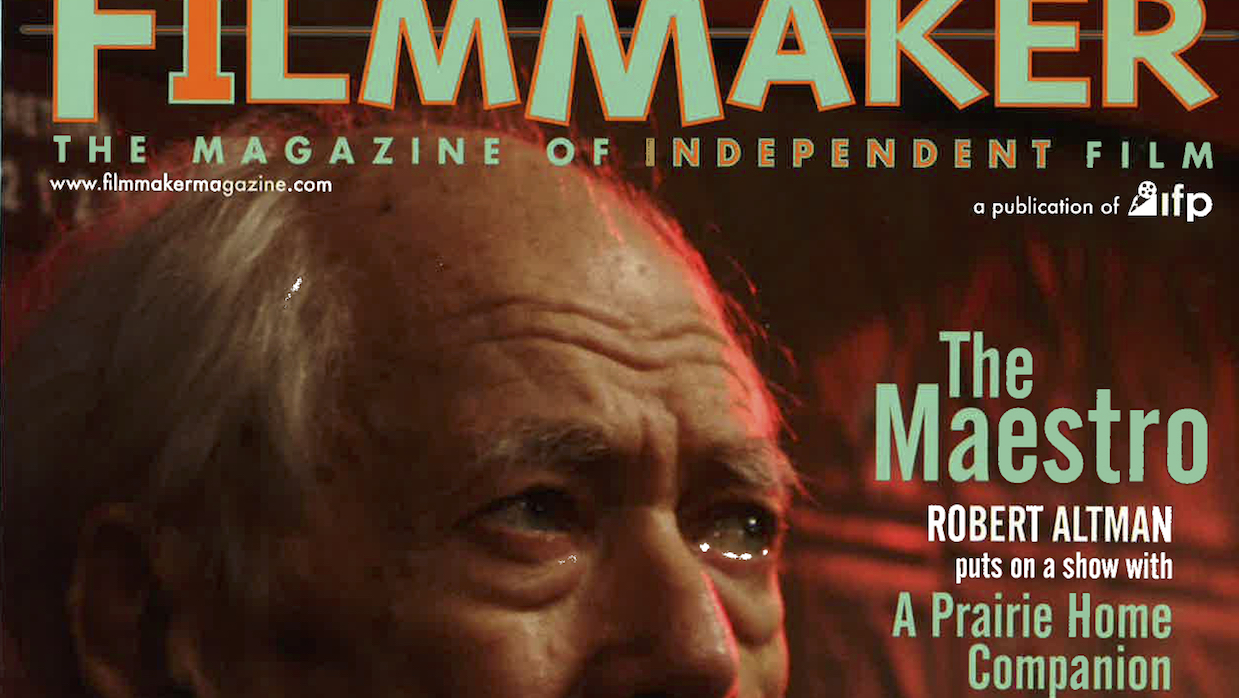

Scott was also a huge supporter of my writing, and he basically gave me free rein to interview just about every great director I sought out. The Filmmaker brand granted me virtually unlimited access to any director with a movie to promote, and I ran with it. Altman, Soderbergh, Linklater, Gondry, Claire Denis, Chris Doyle — thanks to Filmmaker, I not only had access to my heroes, I got to pick their brains, alone in a room, for an hour or so for our long-form Q&A features.

Of course, I never mentioned my own ambitions to any of them, but these interviews served as my film school. I realized early that if I asked directors specific questions about process, they’d invariably brighten up and engage with me. The result was a master class in film directing, and the trick was based on a pretty simple approach: Don’t ask these men and women to tell the same stories they’d been repeating all day (or all week, or all year) about their film’s “message” or what it was like to work with Morgan Freeman or Meryl Streep. Ask them the real shit, from macro questions about how their film’s visual scheme was conceived and then actualized to brass-tacks stuff about coverage, working without any real rehearsal time and what sequences were crafted on the fly and with a drastically reduced shot list because of some unforeseen nightmare that arose. Ask them about directing for the edit (which is all you’re directing for anyway) and who their influences were, and how and where those influences could be felt, whether it be tonally or within a specific camera move.

My takeaway: dozens of lessons of every sort. Here’s a sampling, off the top of my head, from the profound to the profoundly insignificant yet deeply helpful:

- Directing is both an honor and an intensely stressful and lonely experience. If your film is a success, everyone takes credit. If not, you’ll be left holding the bag and the blame. Be prepared.

- A film is never as good as its dailies and never as bad as the first editor’s assembly.

- Everything that can be done in prep must be done in prep.

- Change your socks at lunch. It’s kind of like taking a shower in seven seconds.

- Nothing is impossible if there’s a vision guiding it, and that vision is the director’s responsibility and his or hers alone.

- Said vision must be communicated to dozens of essential people, many of whom speak and listen in very different emotional and intellectual languages, and it is your responsibility to learn how to listen and speak in each and every person’s specific language.

- Take a nap at lunch. (OK, fine, that’s from Sidney Lumet’s indispensable Making Movies, but it’s the best advice ever.)

- The best idea should always win, regardless of whose idea it is. Directing involves a strange blend of confidence in oneself and one’s vision for the film and a total willingness to look for new ideas and new inspiration from one’s key collaborators. They will give you wonderful ideas that you would not have come up with on your own, and it’s your responsibility to create an environment for those ideas to be shared with you without worrying about how they will be received. Coppola wouldn’t be Coppola without production designer Dean Tavoularis. Same goes for Wong Kar-wai and DP Chris Doyle; Scorsese and editor Thelma Schoonmaker; Tarantino and Samuel L. Jackson, etc.

- On that note: If you can’t or don’t trust your department heads, you’re fucked. Either work on your trust issues or hire someone else before it’s too late.

- On a movie set, you must be able to transform, sometimes within seconds, from a deeply focused artist working in a sensitive environment to a battle-ready warrior and back again without skipping a beat or losing your composure.

- Be patient over the course of your edit. Your film will probably suck for a while until it slowly doesn’t suck. Panicking helps no one, especially your editor, who isn’t there to babysit you.

But it wasn’t just the masters who graced our covers and got eight pages of copy who provided me with some of the biggest lessons. It was the up-and-comers, the 25 New Faces selections and the first-time sensations. Some of them would make good on their early promise. Others would fade from sight, sometimes because they got lazy or sometimes became assholes who alienated the people who helped get them there or sometimes because they only trusted themselves. From those nonsuccess stories, I came up with a list of promises to keep once I got my shot:

- Never mistake humility for a lack of confidence. Humility is an absolute necessity, especially when you’re almost certainly the least experienced person of consequence on your own set.

- Work as hard as you possibly can until the film is finished. If you don’t, it will show up on the screen, and you will regret it for the rest of your life. It could also cause irreparable damage to your career.

- No matter how stressful things get, have fun. It might not ever happen again.

- You are the captain of the ship and everyone will be looking to you for guidance. Don’t let them down, and don’t fuck it up.

- But despite everything I had gleaned during my years at Filmmaker and elsewhere, there were dozens of harsh realities I nonetheless had to learn for myself — usually in excruciating fashion.

Let’s limit ourselves to the concept of the actor or actors one needs to greenlight production. To find financing within the broader film industry, you may not necessarily need an Oscar winner, but you do need someone who “means something,” in Hollywood parlance. I’ve always found that phrase pretty telling, especially so its opposite: “Oh, that guy, he doesn’t mean anything.” Tell that to his girlfriend, or his kid, or his dad. And I’m using the male pronoun because that’s who I needed on my first film. To find a male actor, “a Frank,” who would make a financier open their checkbook, was the only path because Frank is in every scene and Lola is not.

For any first-time director, that’s a maddening task, for many reasons. Here are a few:

- You need the support of said actor’s representatives — an agent, a manager, usually both. Agents and managers each make 10% of their client’s fee. On a film of my size ($1–3 million — it varied over time), that means your lead makes something in the neighborhood ranging from SAG Schedule F ($65,000) to the very low $100/day and slightly up range. If a client with major earning power has just finished an indie (or two or three), the reps are almost certainly looking for a payday, as they should be. If so, move on and forget about it.

- There are a ton of terrific agents and managers out there with great taste who will really go to bat for you with their client if they believe in you and your project. Find them and get them the script. Even if it doesn’t work out with the first client they represent, it may work out later down the road, whether it’s for your greenlight-triggering lead or another key role in the film.

- The actor needs to not simply respond to you and your script, but they must also be willing to work with a novice, and do so at a price that may involve losing a bigger payday. And that’s not even counting where they might be financially or psychologically at the moment. Any experienced star or near-star has endured one or more indie shit shows with a newbie who blew it. It’s never fun. If they just went through something like that and have a big offer on the table for a studio film with a more experienced director, your chances of a commitment are basically nonexistent.

- The financier (or group of financiers) has to support the choice, and he or she can often be downright befuddling in the rationale for who is worthy of support. For example:

- At least three of the financiers who were attached over the years to my film used the IMDb STARmeter as their one essential metric. I found this to be ridiculous, as the algorithms aren’t exactly reflective of that actor’s box-office power. That fact was especially apparent whenever that week’s No. 1 happened to be a celebrity who had just died. (When that happened, I managed to refrain from asking whether we should send his now former agent the script!)

- A financier’s taste can be idiosyncratic. He or she may immediately nix a slamdunk choice who was just on the cover of Vanity Fair but be totally fine going with the lead of his or her favorite TV show from five years ago. And while they are attached and willing to bankroll your film, you either need to accept that or look for another investor.

- If someone who neither you, your producers or reps can trust with any degree of confidence suddenly offers up a huge star to be in your film, and then tells you it’s basically a done deal as long as a formal offer is in place, be suspicious — they may just be trying use your offer as leverage to force another, bigger film to sign its own offer sheet. This only happened once to us over the years, but we lost our financing as a result.

- You need a start date in the near future, not a year from now, before you lose the actor, the financier, or both. Both of those things happened on Frank & Lola about a dozen times.

- All of this — the financier’s interest, the actor’s interest, availability or financeability — can change at any moment. In the years I spent trying to get Frank & Lola set up, I can count on two hands the number of times I met with a relatively unknown but wildly (and obviously) talented actor, the perfect Frank or Lola, only to get the usual, “forget it, he/she doesn’t mean anything” response. Then, a year later, said actor would blow up and on bringing them up again to my financiers or producers be met with some version of, “Are you kidding? There’s no way she’ll do our movie. She’s booked for the next two years straight on the new Scorsese/Fincher/Nolan/Tarantino films.”

For eight years, I chased a carrot while trying to gather ants with a spoon in my left hand and herd cats with my right. It sucked. New York to L.A. and back again. I crashed on couches and in motels and even spent a night or two in the ’83 Mercedes diesel Coupe a friend had mercifully tossed my way. The only constant: Frank & Lola in heartbreak city.

At a certain point, most of my staunchest friends and supporters had begun to encourage me to move on. In the eyes of nearly everyone I loved and respected, my once admirable force of will and determination had somehow morphed into a weird, delusional optimism, and people were seriously concerned about me. After eight years, I had become the fool on the hill. But if I quit, that would mean I basically wasted my entire 30s on something that didn’t exist. Besides, what the hell else was I supposed to do? I was incapable of walking away. And I still had a few people in my corner.

And then the universe finally decided to throw me a bone.

October 2014. I’m sitting on an air mattress at my soon-to-be assistant’s house in downtown Las Vegas, where the production had been moved to chase yet another failed financing deal. This time, with actors in place and a crew waiting, I know we won’t have another shot at getting the film made. By the end of the weekend I’ll have to move into my mom’s spare bedroom in Morningside Heights.

Then the phone rings. On the other line: very good news. I had a movie to make. A lot of people might have given up on me by then, but not Scott. He was one of the first people I texted. His response, “Great to hear. Best of luck. Can’t wait to hear the stories when it’s over.”

I tried all of the lessons described above to help me pretend like I’d been there before. I definitely changed my socks every day. I also had the most fun I’ve ever had, with the some of the best and most talented people I’ve ever had the pleasure to know (let alone work with), and I absolutely — 100% — took none of my good fortune for granted. I treated every day on set or in prep like it was the best day of my life, and that’s because it was. Filmmaking is a brutal (and often ugly) business, but sometimes things work out in the best possible way. When that happens, you feel like the luckiest human being on planet Earth. I certainly did.