Back to selection

Back to selection

“Our Culture is in Our Language”: Lisa Jackson on Her VR Film Biidaaban: First Light and Indigenous Futurism

Biidaaban: First Light

Biidaaban: First Light Perhaps the most innovative virtual reality work I’ve seen this year has been Lisa Jackson’s Biidaaban: First Light, which premiered earlier this year at the Tribeca Film Festival. Jackson, an Anishinaabe artist working out of the National Film Board of Canada, has spent years exploring issues of First People identity and language in her work, which includes documentary and fiction film, animation, installations, and other media; in fact, Biidaaban: First Light was designed as a corollary to a multimedia installation.

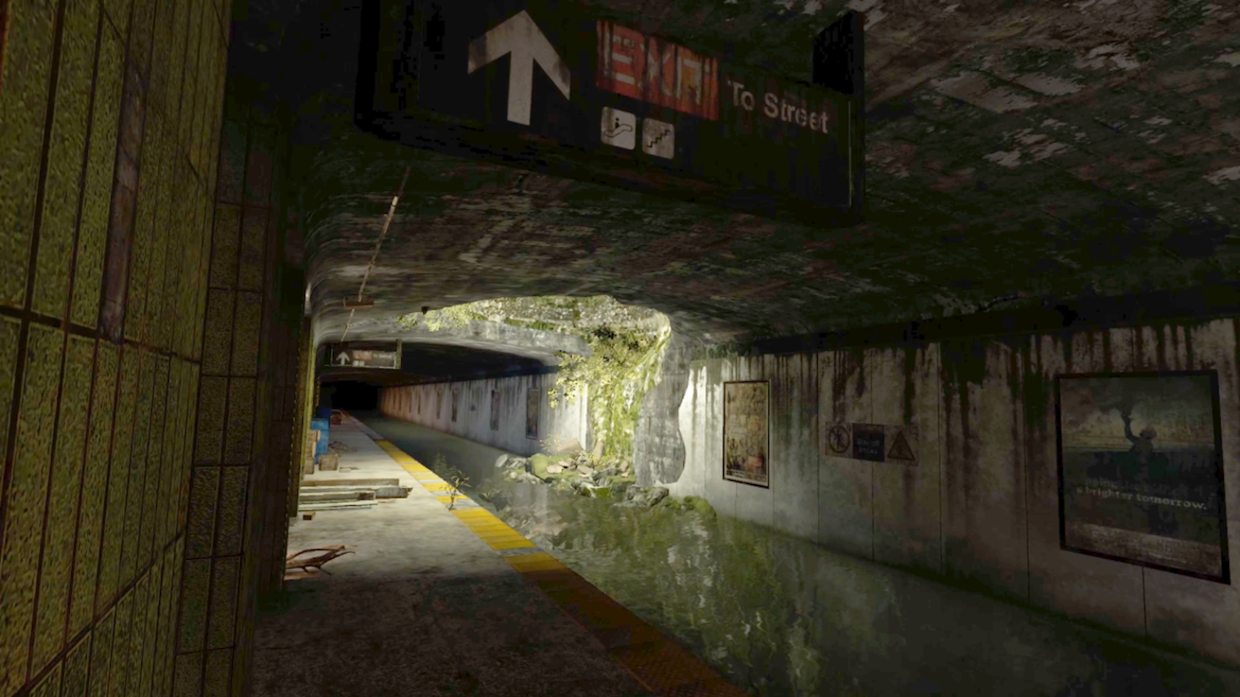

The film’s narrative is minimal. It could be described as a post-apocalyptic scenario in which the viewer witnesses how nature has reclaimed the streets of Toronto after humans have ceased to be a major presence there, but this implies a narrative emphasis on the disappearance of humanity that isn’t there, and, as Jackson explains below, “post-apocalyptic” is not the correct term at all. Instead, humans are rather incidental to the work, at least visually. It shows an urban landscape in balance with nature, a Native American concept often fetishized by European-descended North Americans like myself, but which Jackson and her collaborators manage to create in great detail, making it feel both appropriate and real, a difficult task in a room-scale VR animation. At Tribeca the relationship between reality and virtual reality, nature and technology, was emphasized by the inclusion of a live turtle in a small otherwise blackened gallery space that viewers passed through after experiencing the VR piece. In a huge windowless gallery in downtown Manhattan that was filled with cutting-edge VR and AR experiences, this touch of nature provided the most visceral moment possible, a stark contrast to all the other experiences that, brilliant as they were, remained mediated through technology.

But the balance between nature and man is only half the pleasure of Biidaaban: First Light. As Jackson discusses with me here, the piece’s audio plays as big a role as any of the visuals. By invoking Indigenous voices speaking in their native languages, Jackson’s team created a soundscape that recalls a pre-industrial era, but, more importantly, embraces a future in which respect for the land and for nature can exist harmoniously with technology like virtual reality. We discuss how this may relate to what’s been called Indigenous futurism, but for me another reference point was ambient two-dimensional video games like The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, and Japanese musicians like Hiroshi Yoshimura, whose ambient music reaches a much more natural quality than Western minimalists like Steve Reich. “Biidaaban” is the Anishinaabemowin word for “the first light before dawn,” and it’s appropriate not only for this piece individually but for future virtual reality works that it may presage. This is ambient VR, contemplative, peaceful, natural–not terms usually applied to post-apocalyptic wastelands.

I recently spoke with Jackson about her work, with one question about the future of VR at the NFB answered by Rob McLaughlin, executive producer and head of the National Film Board digital studio in Vancouver.

Filmmaker: Where did the concept for Biidaaban: First Light originate?

Jackson: Biidaaban: First Light grew out of my musing on what a future would look like guided by the ideas in Toronto’s original languages. Indigenous North American languages are radically different from European languages and embody sets of relationships to the land, to each other, and to time itself. Although I’m not a speaker of my language (Anishinaabemowin), I know enough about how different these languages are to realize that seeing the world through their lens would change everything. I understand why elders always say, “Our culture is in our language.” I was floored at how complex they are, in many ways more so than English. Biidaaban: First Light puts us in a rich immersive world and exposes us to some ideas while leaving a lot of room for interpretation, which is why it’s well suited to VR. It can allow the user to see their own thinking reflected back to them and open the door to interesting conversations.

Filmmaker: This isn’t the first time your work has dealt with these languages, and Biidaaban: First Light is being described as Indigenous futurism. Can you talk about what that is and how it relates to your previous work—the spoken text is in Wendat, Mohawk, and Ojibway, of course, but are there other connections you’d like to highlight?

Jackson: My work requires a certain amount of ingenuity to escape mainstream stereotypes about indigeneity. One of the most prevalent ones is that anything native has and can only exist in the past. Of course, Indigenous cultures continue and have no trouble co-existing with hip-hop, cortados and pop culture. Indigenous futurism is a way to step past those stereotypes to something more thoughtful and sophisticated where we imagine our cultures and thought systems in the future. For example, lately I’m hearing a lot of discussion around the nature of time itself as a linear construct and how indigenous concepts of time are circular and what that means. It’s about building a world that can show us something fresh and shake us out of our inability to envision a future different from where we are without calling it “post-apocalyptic.” Because if you take a different perspective, the apocalypse has already happened.

Filmmaker: Can you describe your process creating the audio for the piece?

Jackson: With Biidaaban: First Light it’s important that we hear the hum of life—crickets, birds, etc.—and that there is enough sonic space to just be. I often work with audio that walks the line between sound design and music. Fader Master Sound Studios, who created the soundscape, got that subtlety. There can be a tendency to rely heavily on music and sound design to push the viewer this way or that way in their interpretation or emotions. I would rather use a lighter touch and allow the user to have their own feelings.

Working with the speakers to include the Indigenous language elements in an appropriate way could be a whole article in itself. It was a powerful part of the experience of making Biidaaban: First Light and I’m grateful for the expertise and thoughtfulness the speakers gave to this piece to make sure it was done accurately and with respect. Hearing the languages is very moving for many who experience the piece and knowing that young indigenous people can listen to their languages spoken in a future world like this is very exciting. I can’t wait for it to travel to communities.

Filmmaker: You’ve worked with a variety of formats—2D films, 3D films, 360-degree film, and fixed-point VR. Is this your first room-scale virtual reality piece? How is that different than these other modes of filmmaking?

Jackson: Yes, I’ve done one 360-degree documentary video, but this was the first piece where I was able to create a new world that is so complete, working, of course, with the brilliant 3D artist Mathew Borrett, whose detailed vision of a future Toronto meshed beautifully with the ideas of my piece. I’ve always given a lot of attention to the spaces I create in my work. I want them to be specific and have a certain feeling. Also, I’ve been moving towards bringing a sense of the physical and concrete to my films and they can be quite visceral. Biidaaban: First Light is an extension of those concerns, and also adds in a new piece, which is my desire to give the viewer more agency in experiencing the work—making them meet it halfway in a sense, rather than passively receive it. Physically being able to move around in such a hyper-real environment is thrilling and puts us in the driver’s seat. It really feels like you’ve visited this future Toronto, rather than having “watched” something. We even see people reach out to touch elements of the world, so complete is their immersion.

Filmmaker: What do you envision for the future of virtual reality and immersive art in the next few years, specifically for Indigenous or Native voices? What do you hope to work on next yourself?

Jackson: I want youth to experiment with these mediums; I want to see the worlds they can create. And there are so many incredible Indigenous visual artists in Canada., I’d be keen to see what they can bring, since in some ways this work is more akin to walking into a gallery than going to a movie. There may be more VR in my future, as I’ve developed a bit of a bug for it, but for now I’m pushing the physical angle even further and am in the process of creating an immersive three-part multimedia installation called “Transmissions.” It’s a sister project to Biidaaban: First Light and looks at the same themes. I’m also at work on a short IMAX film called Lichen, as well as a couple more traditional film and TV projects.

Filmmaker: I’m also curious about the state of VR and AR production at the NFB. As NFB/Interactive is expanding I’m interested in what’s happening there overall and how producing a VR piece like this may be different there than with private investors or other institutions like the CBC.

McLaughlin: The NFB has a long history of exploring new technologies and their creative potential to engage Canadians with story and art. VR/AR and MR are the latest to emerge that could dramatically change the way we interact with and consume our stories, and ultimately change the way we interact and connect with each other.

As Canada’s national public producer of contemporary audio-visual works, we are committed to building understanding and exploring the Canadian sense of self, at home and around the world. We are not a broadcaster and are not constrained by established formats and channels. We work to produce distinct and unique projects across a wide range of experiences that can find their way into classrooms, communities, cinemas, festivals and homes via the internet. This ability is proving extremely valuable in exhibiting VR works and helps distinguish our unique role in Canada.

Also, our ability as a public cultural agency to build teams and actively work with artists of all stripes to take creative risks, or tackle important topics and issues, sets us apart from private investors looking for monetary returns, or from public funding agencies who take an administrative approach to production. The lessons we are learning from the hands-on producing of VR/AR pieces are transferred from project to project and artist to artist as we explore what works and what doesn’t across all these emerging forms.