Back to selection

Back to selection

Onrushing Now

Nick Nolte had walked into a bar.

Nolte was a constant in a screenwriting partner’s Malibu hinterlands, hair ever elevated, stalking across a parking lot to Coogie’s for the midafternoon breakfast, resplendent in striped Sulka pajamas and happy dudgeon.

This time, it was dark and it was Toronto, across from the Sutton Hotel headquarters of the festival. The upstairs of now long-defunct Bistro 990 on this night in the late 1990s is rich with heightened voices but not shouting. I’m standing near Nolte with a cofounder of Indiewire, Mark Rabinowitz. Our eyes literally grow large just as our ears figuratively open wider.

“I’ve had all kinds of doctors,” Nolte says, “I know all sorts. As a man who’s crossed the line past 50, I have questions that only a doctor can answer. So this doc I’m getting to know, he knows me better inside than out, I ask, ’Doc, there’s one thing I have yet to trust a doctor with, and I like you, I just have to know…. A few years ago, I started having this problem, and it’s only gotten more pronounced, I just gotta know. Doc, my balls started to drop and now they’re all but down around my knees,’ and he says, ’Two words, Nick: Testicle tuck!’”

The room stills, like a tuning fork, still vibrating, and a burst of joyous laughter breaks out as the loud, patterned shirt less than a yard away turns out to be Terry Gilliam. “Nick! Nick!” Gilliam giggles. “Nick! A testicle tuck! Bless you. This is all I need from life. I must meet your doctor. Oh, sorry, I’m—” “Good to meet ya, Terry. Your movies make me sad in the very best way.” Looking away from this delicate moment toward the front of the bar, I notice a tall Asian man standing, looking out onto Bay Street, where taxis queue in front of Bistro and the hotel. Wong Kar-wai is watching taillights.

“This was the one moment in my filmmaking career that I sensed I was working in an environment where the filmmakers had the same goal, had the same sensibility,” Olivier Assayas recently told Filmmaker about the end of the twentieth century. These are those streets; these are the street corners and alleyways.

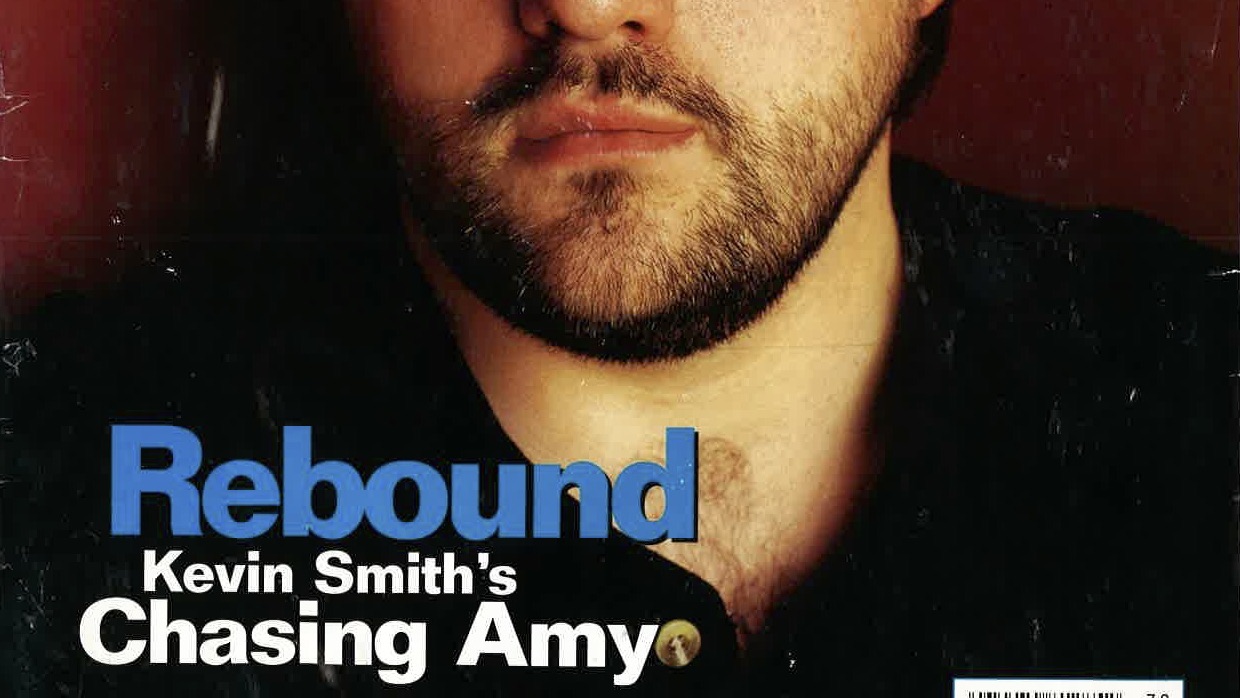

My first story for Filmmaker was the spring 1997 cover article about Chasing Amy, with Kevin Smith and Scott Mosier, a couple of years after Clerks arrived as part of John Pierson’s Spike, Mike, Slackers & Dykes patrol as well as the Miramax onslaught to come. Which is more the 1990s image? Smith asking, when he visits Chicago to promote Clerks, for the inside scoop on the real Shermer High or watching Smith and Harvey Weinstein smoking and laughing outside the top-end publicists-favored Toronto bistro at Bay and Bloor?

My mind races to James Schamus a few years later, across the road in the roundabout in front of the Hyatt, as he stands in the plain northern sunlight telling me that he has only a couple pieces of paper left of 112 or so to complete the finance for a movie called Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. The air smells of Ontario autumn and bus fumes. “It’s probably more satisfying than writing a script.” Schamus compares screenplay construction to a cross between carpentry and poetry, but this is also a time to master chain of title, interlocked international ownership: acrobatic feats of fiscal legerdemain.

There are unlikely meetings with movies, too, such as the Toronto press screening of Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act Of Killing on the huge Scotiabank IMAX screen. There is the bright light—ideally, the biggest bright light—and these pinpoints are flickers, firefly light to accompany the campfire of cinematic storytelling.

This crisscrossing would extend into an indefinite future, surely, a compound matrix of matrices of acquaintance and similar hopes. But of course, like the movies themselves, they are only part of an onrushing now, ever present, but as memory, elusive instants amid a congeries, a congress, a confluence of taste that we now know would not abide.

Wouldn’t there always be a Hal Hartley every year? Wouldn’t Daughters of the Dust establish Julie Dash as a master? Hasn’t the moment arrived? (Yes, money made the movies happen, and the weft and warp of vainglory—another subject, thousands of words worth.)

Maybe 10 years ago, Werner Herzog. He is accompanying a complete retrospective of his movies in Greece and, as he is opening the 10 days in residence, sits at a table with motley press and the Bay of Thermaikos behind him. “I shot a film on these shores when I was 16,” he says, gesturing behind himself. “I was strong but stupid. Walking made me stronger.”

A few days later, Herzog is walking alone toward a warehouse where images from his films are to be presented, hands clasped behind his back, along the cobbles of the pier where the festival unfolds and where Angelopoulos shot several tragic scenes for his movies. The sky is gray and gray alone. He notices me. “Beautiful sky! Let us look at these terribly sad photographs.”

Fragments come in topographic waves. Not only when you’re standing on a particular street corner in Thessaloniki or Buenos Aires or Marrakech or Winnipeg or the Wasatch Range.

More than 10 years ago. Sundance. Park City. Dolly’s Bookstore. Harvey Weinstein stands encased in a spanking-new puffer jacket with lavish fur trimming. He’s watching several women standing in the film section, his palm flat on the top copy of a tall stack of Everyone Poops.

Another moment, another year. Early for a show at the Egyptian Theatre up the hill on Main Street, I stop into Dolly’s Bookstore. I push the complimentary copy of the New York Times that I had gotten from the headquarters Marriott on Sidewinder further down in my bag. John Cleese is at the counter, standing slightly pitched like a bird dog. “Will anyone have the Times, then?” he says, clipped. “Not this time of day,” the clerk says. Cleese strides out with his friends behind him.

At the curb, I stand next to him. “Your Times, Mr. Cleese,” I say as I reach into my bag and fold it crisply in half. He looks at me as if I am both crazy and reason itself. “Of course,” he says, taking the folded paper under his arm and stepping into slow-moving traffic.

A less logical older man: Larry Clark in Greece receiving an avalanche of faxes, an ouroboros of smudgy disappointment, a few days after savaging a distributor over a London dinner. Some of the faxes are about that incident, others from sales reps he dislikes and mocks as the endless page continues.

Roger Ebert liked to doodle and later liked to take portraits. I’m sitting in a shaft of sunlight in a Sundance hospitality suite and Roger, nearby, raises his voice: “Old man!” I look up. I look down. “Now that’s a good one,” he says, snapping a perfectly framed picture of an overtired journalist.

The Abasto shopping mall in Buenos Aires, 150-plus stores and a dozen-screen movie house carved into a vast, gorgeous public market that had been built in 1893, and only a few yards from where tango master Carlos Gardel grew up and lingered. Plus, a fast-food café where Jonathan Rosenbaum is smiling his most amused smile at whatever Claire Denis has just said. I don’t remember what Claire Denis said; I remember white t-shirt, sleeves rolled up lightly like Levis cuffs, a cigarette—Marlboro?—and a pleasant, compact slouch. “Why don’t you smoke?” I remember that question. I don’t remember her explanation of why I should return to the habit.

Agnès Varda in Greece, the diminutive but vastly generous filmmaker in a polka-dot dress, large white dots on a navy dress, twirling gently along the cobbles of a pier at the port of Thessaloniki, the azure bay and a ghostly Olympus providing backdrop. Agnès dances, Agnès smiles. She stops and asks the festival director, “Michel! Do you know a Greek song? Sing a Greek song.”

Chicago, more recently. A small dinner party where all hell breaks loose. A heartbroken, drunken cater-waiter turning the evening into a sustained set piece of physical comedy. “Tati?” I lean over and whisper hoarsely. “Oh, no,” Varda says, delight dancing in her eyes. “Blake Edwards! Let us pray, Blake Edwards!” I forget her age in a twinkle: She is 88, but her delight a child’s.

Thessaloniki on many occasions: The great director Theo Angelopoulos, also the festival president, listening to a foolish question in Greek or in French and his eyes turning into black coals and his face growing stern and usually a single word in reply: “óx ,” or “Not a chance,” in his low intonation.

And the year Angelopoulos presents an award to Werner Herzog on the stage of the Olympion, the central movie palace of Thessaloniki on Aristotelous Square, and then seating himself a few rows back for the feature presentation, Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans. From a few rows back, Angelopoulos’s distressed body language is more compelling than Nic Cage’s hallucinations, and the great Greek’s abrupt exit is as if from a catapult.

Toronto in the press hospitality suite at the end of the century: A now-reformed film critic of note expresses surprise at the balance of interviews to movies on my schedule. What do you learn from just meeting a man or woman you won’t learn from their movies, he asks? I don’t have an answer. The actress with shoulder-length honey hair (like Bardot’s in Contempt) whom I had interviewed a few hours earlier is in the lobby.

“Are you headed back upstairs?” she asks. “Yep. More interviews, tenth floor,” I say.

The elevator doors open, and the large compartment is empty but for a middle-aged man with wiry hair and large glasses standing in the corner. I look back to her in cartoon terror. “What?” she mouths. “Him! You know—?” I mouth. She shakes her head.

He’s in tennis whites, his eyes down, tennis racket in one hand, a half-smoked stubby cigar in the other. “You’ll have to forgive me,” I say quietly. “Who is he?” she says. I take a lonnng comic slide forward, not quite a Funny Walk but a sight gag nonetheless. The man looks up with the slightest smile.

“Monsieur Godard?” A small but perceptibly grave nod. “Oui.”

I’m trying to say the word without the entire story tumbling out, remembering the lore of when the young Swiss film critic met Roberto Rossellini at the Venice Film Festival and stood close to him and stated, “Maestro.”

Deep breath: “Maître,” I say, and step back a self-aware step. He smiles. “Rossellini? Il y avait un maître!” The doors open.

Exit: Godard, followed by a tennis racket.

The most chilling sound I ever heard at a film festival is on a Sunday afternoon in the spring of 2012. Everyone in the 1,500 or so seats knows the attraction in the Virginia Theatre in Champaign, Illinois: a projection of the Blu-ray of Citizen Kane, on the big screen, with Roger Ebert’s time-honed commentary playing over the soundtrack.

Roger hadn’t spoken since his surgeries of 2006. Heavy red velvet curtains part and the words “An RKO Radio Picture” appear—a radio tower girdling the globe and transmitting worldwide—with the dialogue underneath: “This is Roger Ebert, watching Citizen Kane with you.”

And Roger is watching Citizen Kane with us, from a lounger at the back of the auditorium. But it is the simple manifestation of that stilled voice—chummy, smart, ready to entertain and edify—that makes the heart jump. Ebert’s two-hour weave of history and observations rushes forward, a dispatch from a friend long unheard.

The last words spoken from the screen: “I’m Roger Ebert. I hope you’ve enjoyed seeing Citizen Kane.” The curtains close, the lights rise, the room rocks with stifled sobs and fills with honest tears.

Onrushing Now is part of a work in progress.