Back to selection

Back to selection

Projecting the IFP: IFP Week’s Original Technical Director David Leitner on His Celluloid Nailbiters

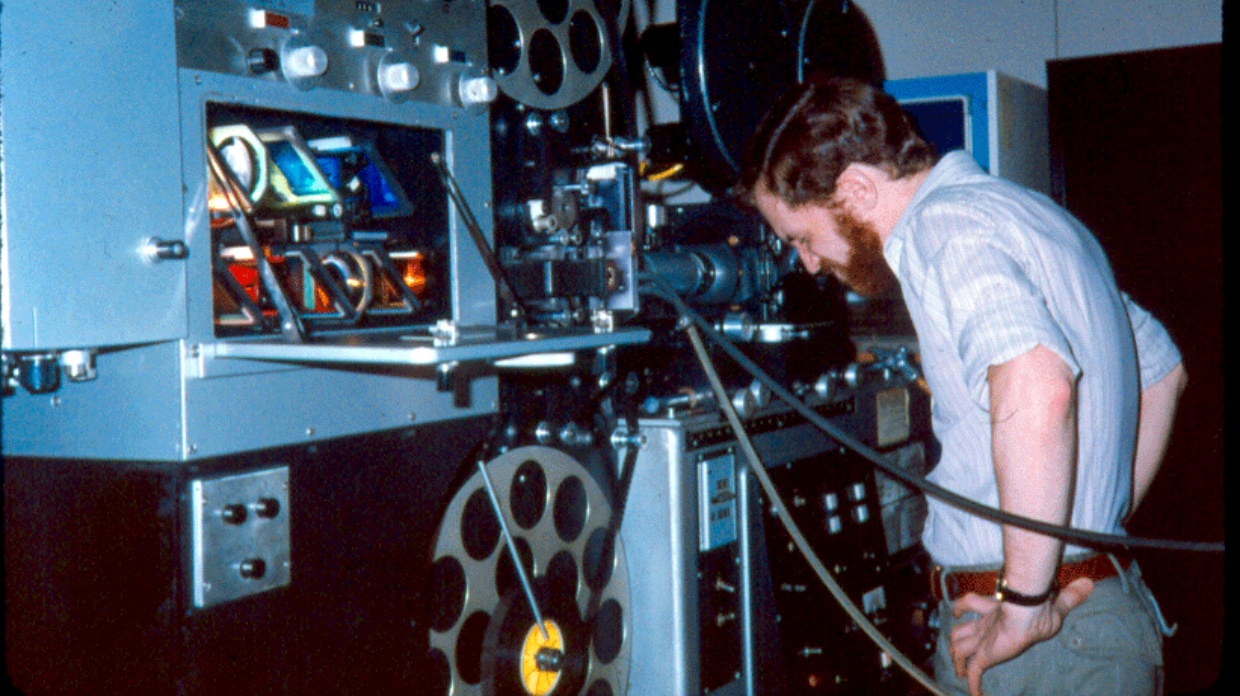

David Leitner with DuArt's optical printer, circa 1982

David Leitner with DuArt's optical printer, circa 1982 I was technical director of the Independent Feature Film Market from 1986 to 1993, and a member of the Independent Feature Film Market Committee from 1989 to 1993. I attended all prior IFP markets too, starting with the first one, a sidebar to the New York Film Festival.

Those early IFFMs were a DIY affair, as scrappy, often broke indie filmmakers maneuvered to squeeze every advantage out of this novel new showcase, navigating its opportunities and inventing new ones. Nothing like it had existed before on the American indie scene.

Two memories in particular are dear to me. The first involves Ross McElwee and Sherman’s March. The second, the opening of the Angelika Film Center.

In 1986 there was no Internet or social media, not even DVDs (they came 10 years later). It was high noon for the VHS vs. Betamax gunfight, and in the confusion not everyone yet had a player. If they did, which one? As a result, screeners were costly, bulky 3/4-inch U-Matic cassettes that had to be lugged around or mailed. They piled up in the offices of festival programmers, who preferred instead to watch prospects for their festivals on the big screen. Hence the super-critical role played by the IFFM.

In the fall of 1985, as I was ending my stint as Director of New Technology at DuArt Film Lab and preparing a return to filmmaking, I intervened in a situation at the IFFM that appeared to spell catastrophe for filmmaker Ross McElwee. Just as filmmakers today pull out all the stops to finish last-minute postproduction in the run-up to a Sundance premiere, so too a crunch atmosphere would envelop DuArt prior to each IFFM.

The majority of films at the IFFM in those days were 16mm—analog video was not deemed exhibition quality—and indie-friendly DuArt was the lab that developed and printed most of the films shown at the IFFM. So when a dozen or more films suddenly, at the same time, needed A&B roll matching and cutting, sound mixing, color timing, composite answer printing, 2nd answer printing, and so on, there were bound to be train wrecks. Each of these steps took weeks to get right in the best of circumstances. However, Ross McElwee’s new film was 2 1/2 hours long. That’s five 1,200-ft. reels of 16mm composite (with sound) color prints, which he needed to deliver to the basement screening room of 2 Columbus Circle — then the NYC Department of Cultural Affairs, now the Museum of Arts and Design — before his time slot in the IFFM screening schedule. If he missed this deadline, no one at the Market would see his film.

I somehow recall that, whether from exhaustion or contagion, during this frenzy of lab work he suffered a terrible head cold—but this would prove the least of his problems. It became clear that the lab, working around the clock, could not finish five reels with composite sound in time for his Market screening.

As I’ve explained, this was a life-or-death situation. No one would see the film if it wasn’t ready in time to be projected. Perhaps the lab could finish two or three reels with sound… what about the remaining ones? Ross had silent answer prints of everything, prints made without sound to check color and effects. Was there a way to project these soundless reels in sync with his 16mm magnetic tracks? I knew of a portable 16mm projector that could play, in sync, a 16mm mag track in parallel to picture, where the projector looked as if it had reels of film slowly turning on both sides, which essentially it did. The German company Siemens made such a projector for screening sync’d 16mm dailies on location. Was there one in New York? I called around (maybe Ross did too, I don’t remember), and miraculously we located one at Camera Mart, a once dominant camera rental house on West 55th Street that’s now largely forgotten.

It was located a few blocks west of DuArt, and I scrambled over there. What I found was both promising and unsettling. The projector looked as if it hadn’t seen action in decades. I’m not sure it was suitably adapted to 120V either. I opened the lamp house to inspect the bulb and was shocked to see that the quartz bulb of the tungsten halogen lamp had expanded backwards and conformed to the shape of the concave metal reflector, presumably from overheating. Surely you have another bulb, I asked? Nope, that’s it, said Camera Mart. Take it or leave it.

To my amazement, when I turned on the projector, the swollen bulb turned bright. Bright in a dim, dirty yellow way. At least it was something. We’d have to risk it.

The next problem was a human one. The projection room in the basement of 2 Columbus Circle was a union shop. This dim German projector from Camera Mart would have to be set up closer to the screen, which meant in the middle of the auditorium’s seating, on a raised table erected temporarily for this purpose. This arrangement violated every possible union rule. Nor did the union projectionist want to be responsible for a projector he didn’t know how to operate. There was only one path to take: bribery.

He was a cheap date. Two six packs of beer did the trick. He agreed to project the first several completed reels from the projection booth, then let me take over. From that point I would take responsibility for operating the double-system projector in the auditorium.

I think three completed reels were projected from the booth, and maybe two from the dim, rickety Siemens on the floor. It’s been many years, and exact details easily melt into oblivion. Maybe Ross remembers. Just the act of writing all this down for the first time has challenged long-dormant synapses. But there’s one more twist to this story.

The take-up on the projector’s picture side was driven by what looked like a loop made of springy steel coil. It was supposed to fit snugly over a pulley wheel attached to the take-up spindle. In practice, it flopped loosely. I’d been so concerned about light output that I’d neglected to test the take-up. The Siemens wouldn’t pull more than a few hundred feet before spilling film onto the floor. If memory serves that we did, in fact, project two 1/2-hr. reels of 16mm picture and 16mm full-coat mag from the auditorium floor, this means that I spent an hour on my feet standing next to a loudly chattering projector, with my finger in the take-up reel, turning the take-up by hand. Not the most comfortable way to take in a brilliant and unforgettable film.

What redeemed this saga of unrelenting pathos? In the sparse audience that day was a rep for the Berlinale. Sherman’s March as a direct result of our kludged screening was invited to premiere at the 1986 Berlin Film Festival the following February, to international acclaim. (Alongside other greats that year at Berlin: Shoah, Partisans of Vilna, Vladimir Horowitz: The Last Romantic, A Zed and Two Noughts.) The following January, it won the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance.

Such was the unprecedented potential of the IFFM to springboard new American indie films.

Similarly, my 16mm documentary, Vienna is Different: 50 Years After The Anschluss, was discovered at the 1988 IFFM at 2 Columbus Circle and invited to premiere at the 1989 Berlinale, which led to a U.S. premiere at the 1990 Sundance. In our case, DuArt came through with flying colors (pun intended). Thankfully no screening-room heroics were necessary. As for that Siemens double-system projector, I’ve long suspected I was its last renter. I’m willing to bet it wound up in a dumpster, like so many rewinds and split reels and upright Moviolas did in the 1990s after digital swept in.

For the following year, 1989, the IFFM moved downtown to the Angelika Film Center, and my second, briefer anecdote concerns the IFFM’s role in inaugurating the Angelika. Creating a downtown independent cinema on Houston Street was a bold move in those days. The Film Forum on Watt St. showed that it could be done (it too would locate to Houston St. a year later), but the area was rough around the edges and empty at night, a far throw from the thronging sidewalks and tree-lined boulevard we enjoy today. Undaunted, producer Joe Saleh and wife, producer/actor Angelika Ohl, had transformed a musty basement that warehoused remnants of a 19th century cable car power station, clearing it of massive iron machinery, and carved out what I believe was the first downtown multiplex.

The IFFM, champing at the bit to find better accommodations, lept at this chance to move south. The only problem was that the Market’s dates were fast approaching and the Angelika’s renovation was still underway. Luckily, Angelika’s 35mm projectors were already in place. Since I had considerable experience testing 35mm projection, I did so. (In the early 1980s, I created the familiar DuArt SMPTE RP-40 projection alignment film, with “DuArt Film Lab” in red, green, and blue lettering, which the lab would cut into the leader of every 35mm print.) At Angelika, I was first to test the new projectors for alignment, gate size, keystoning, jitter, shutter sync, field brightness and evenness. There was no one to tell me not to make these adjustments. I felt that with the 1989 IFFM about to begin — which did indeed take place before Angelika opened to the public — we had an obligation to the filmmakers to ensure that their films looked their very best. We also rented, installed, and tested a 16mm projector, but that’s a footnote to the remarkable fact that the now-iconic Angelika lost its theatrical virginity to the Independent Feature Film Market of 1989.