Back to selection

Back to selection

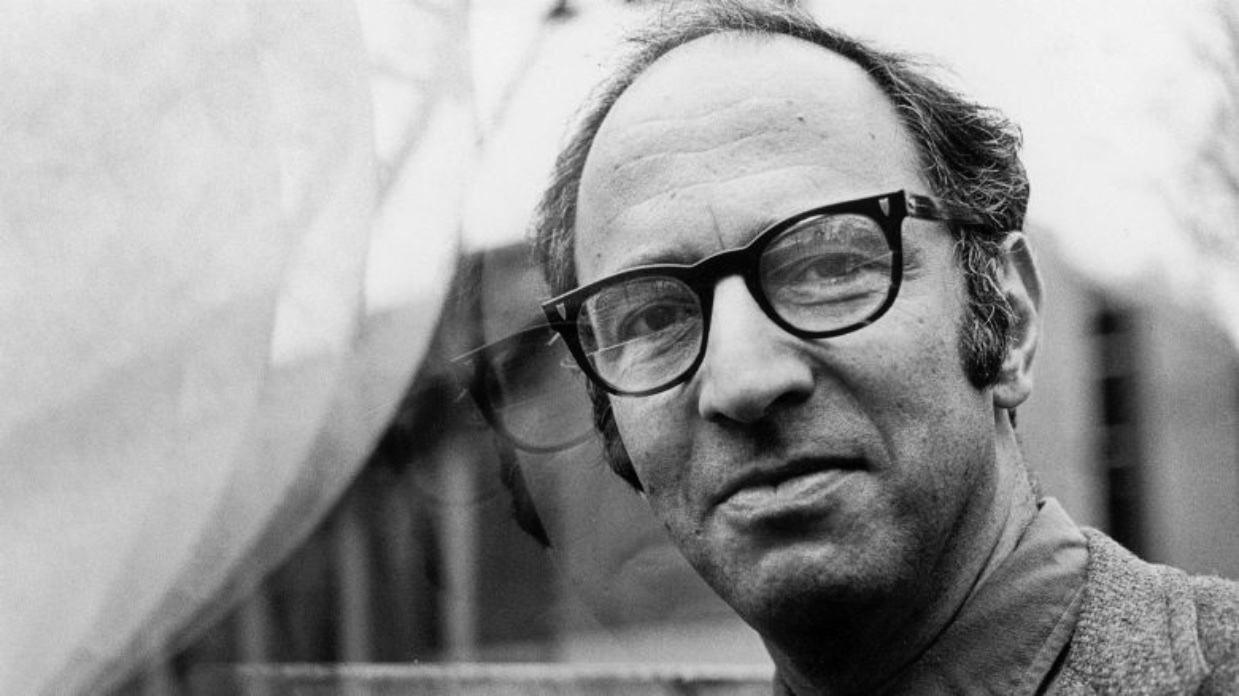

“There’s This Idea that Filmmakers are Social Workers, Which They’re Not!”: Errol Morris on His Portrait of a Holocaust Revisionist, Mr. Death

The following interview of Errol Morris originally appeared in Filmmaker‘s Fall, 1998 issue.

In 1988, Fred A. Leuchter, an engineer from Massachusetts who made a living designing more “humane” electric chairs, was hired by Ernst Zundel, the publisher of several pro-Hitler, Holocaust-denying tracts, to conduct a forensic investigation into the use of poison gas in Nazi concentration camps. On his honeymoon, Leuchter travelled to Auschwitz and, with his wife sitting in the car reading Agatha Christie novels, illegally chipped away at the brick, collecting mortar samples which he transported back to the States. Testing these samples for traces of cyanide gas, Leuchter “proved” that the Holocaust never occurred. Taking these findings, Zundel published The Leuchter Report, which sold millions of copies around the world, and was later tried, in Canada, of disseminating “false history.” Leuchter, of course, was the main witness for the defense, and at the trial his callously sloppy science was thoroughly discredited. In the process, Leuchter lost his wife, his reputation, but not, as Morris shows us in his philosophically probing and horrifyingly funny documentary Mr. Death, his plucky American “can-do” attitude.

Fred Leuchter is the latest in a long line of American originals framed by the amiably merciless camera of Errol Morris. His first film, Gates of Heaven, comprised heavily of talking head interviews, is a classic portrayal of two feuding pet cemetery owners that resonated on social, political and economic levels. His 1988 film, The Thin Blue Line, blended interviews with dramatic re-enactments and surreal visual flourishes to solve the mystery of a small town murder. And, in 1997, Morris made Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control, a tremendously moving portrait of four obsessed individuals whose singular pursuits Morris merges into a visually stunning meditation on death and mortality. His latest, Mr. Death, an Independent Film Channel production, is a worthy addition to the Morris canon, a startling, deceptively straightforward work in which Morris’s engagement with his subject, Fred Leuchter, creates a knowing and cautionary cinematic portrait of a man who is incapable of knowing himself.

Filmmaker: Mr. Death deals with a lot of issues – epistemology, belief systems, how one forms one’s own identity – and then there’s the whole subject of Holocaust denial. Were you worried about making a film where a large part of the media is probably only going to deal with that one issue, the Holocaust, which to me is not really what the film is about?

Errol Morris: I agree with your assessment of the film, but it worries me that you’re already pre-judging how people are going to respond to the film, as if it has to be that way.

Filmmaker: Well, there certainly will be people who will view the film as being successful or unsuccessful in how it presents this controversial subject.

Morris: Yes, and there’s a long article that appeared in The New York Observer written by Ron Rosenbaum on “Errol Morris and the Tricky Art of Refuting Holocaust Denial.” It is certainly worth reading. But to a lesser extent, I had similar problems with The Thin Blue Line. That film is an attempt to have your cake and eat it too. To paraphrase what you just said, it was an attempt to make a movie about how we see the world, various epistemic concerns, how believing is seeing for many people, if not for all of us. And it told a story about a miscarriage of justice. Without making any kind of exact comparison between The Thin Blue Line and Mr. Death, there are similar kinds of problems. In The Thin Blue Line it became absolutely imperative in telling the story to make it clear that there was a miscarriage of justice, that David Harris was in all likelihood the killer and Randall Adams was not. And in this movie, it becomes absolutely necessary to make it clear that the Holocaust happened and that the Leuchter report is devoid of value. It would have been irresponsible not to.

Filmmaker: There’s a paradox at work here. As a subject matter, the Holocaust is capable of dwarfing all of the film’s other philosophical concerns. But, in a way, the enormity of the Holocaust is exactly what causes these concerns to register on the deepest possible level.

Morris: I agree. One person asked me: “Why this interest in murder in your films?” And to the extent that I know, I believe it’s because we are deeply fascinated with why people do things. Asking the question of why someone crossed the road on a certain date at a certain time lacks drama. Murder is such a dramatic event that we feel compelled to provide an explanation for why it happened. We get drawn into all of these philosophical issues about how we know things, about the nature of explanation. Another tricky element of course, is that I never at any time in the course of making this movie or The Thin Blue Line, wanted to convey the idea that truth is subjective, or that I believe that truth is subjective, that I’m some kind of post-modernist in that respect. One thing I am fond of saying about Cambridge, Massachusetts is that the name Baudrillard does not appear in the phone book. And this is not a film about how history and truth are up for grabs. This is far more old-fashioned in the sense that I believe in facts, knowable facts. Maybe the reasons people do what they do are more elusive, but the question of whether or not poison gas was used in Auschwitz is not something of conjecture. It’s something that has been established overwhelmingly with historical evidence.

Filmmaker: How did you meet Fred, or how do you find people like him for your films?

Morris: People always ask me these questions as if there’s some kind of algorithm that can be cited. I’ve come to realize that maybe it comes down to some kind of talent that I have, for better or for worse. I think I share with my mother, who died a number of years ago, the quality of being really interested in people. And I think what’s interesting about interviewing is that it is a kind of model of human interaction on some kind of formal level – the relationship of one person to another person. Yes, the rules change. In some cases, there’s supposed to be a lot of interaction, and the drama derives from that fact. In, say, a Mike Wallace interview, it is presupposed that part of the nature of the interview is an adversarial relationship between the subject and the interviewer.

Filmmaker: How do you situate yourself on this continuum of interviewers?

Morris: I think I’m almost the polar opposite [to Mike Wallace], because my intention is to create monologues, to remove myself from the interview process as much as possible, even though I’m very much there.

Filmmaker: But at the end of this particular movie, Mr. Death, we hear your offscreen voice asking a question to Leuchter.

Morris: It’s become a stylistic thing with me. I’ve done it now in both Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control and this movie by choice, and in The Thin Blue Line I was there just by necessity because I needed to put that material in the movie. But I like it, it’s this reminder that there is this other person out there, and I think that the question registers my puzzlement with Fred, and maybe at the same time, captures the audience’s puzzlement with Fred.

Filmmaker: Have you heard from Leuchter after the film was finished?

Morris: I showed him the film.

Filmmaker: What does he think of it?

Morris: He liked it.

Filmmaker: There’s an irony here. People accuse Leuchter of being megalomaniacal, of naively believing that his own faculties can refute the historical evidence of the Holocaust. But that same kind of presumption is probably what motivated him to agree to do your movie and to perhaps believe that he would come off looking good.

Morris: That’s probably true. When I see Leuchter at the end of the movie on his rock pile, pounding away, it takes on this very sad significance, because at that point in the movie, you realize how empty his enterprise really is. That image has a kind of existential barrenness that I find interesting. It’s one of the strongest metaphors that I’ve ever stumbled on. To me, the two central images in the movie are the Van der Graaf generator at the beginning which you see reprised at the end, and the shots of Leuchter on the rock pile. In fact the rock pile was a re-enactment done in the studio in Boston. We built a piece of Auschwitz, and there Fred is, pounding away again.

Filmmaker: Why is the Van der Graaf generator one of the central images for you?

Morris: Well, let me ask you a question. What did that image do for you?

Filmmaker: That image to me connects to the tradition of the mad scientist — the ’50s inventor doing home-made science in his basement.

Morris: That’s certainly intended. It’s intended to invoke Frankenstein and a self-invented inventor. But I also saw the image as this man who sees himself in possession of certain knowledge, who sees himself almost as a version of God, as the arbiter of what is death and what is life. And putting it at the end of the movie in juxtaposition to Fred on the rock pile – it’s like, “What is he doing?” It’s the quintessential picture of benighted humanity engaged in a totally quixotic, meaningless, and senseless – if it weren’t also so deeply pernicious – enterprise.

This is a story about a clueless narrator. Or is he a clueless narrator? I see the film as a kind of Citizen Kane. A movie where you have various characters speculating about [a subject’s] underlying motivation, but we never really know for sure who he is and what he’s doing, or, if you prefer, why he’s doing what he’s doing.

Filmmaker: I was surprised throughout the movie at Leuchter’s lack of interiority, his lack of any kind of philosophical introspection about what he was engaged in. His enterprise seemed purely mechanical, divorced from society, culture or politics. And also, there seemed to be something truly hapless about his adventure.

Morris: To me, certainly there is something hapless about his adventure, but don’t forget that one question I ask him in the movie: “Fred, did you ever consider the possibility you might be wrong?” And he says, “I’m well past that.” And to me, this is getting into a kind of crazy area of megalomania. What’s so interesting about how Leuchter tells his story is that he himself points out in the early part of the movie that prison officials were mistaken in assuming that because he had expertise in one area that it extended to other things as well. Because he could build electric chairs, that didn’t mean he could build lethal injection systems, or gas chambers. He ridicules them for making this assumption. And then we learn a short time later, that he has bought hook, line and sinker into this whole Zundle-defined enterprise of going to Auschwitz on a fact-finding trip. He has no expertise, yet he manages to sell himself to himself as the final arbiter of these things. And to me that goes well beyond “hapless.”

Filmmaker: When you ask him that question at the end, most intelligent people could say, “Yeah, I’ve thought about it,” or “Maybe I am wrong,” but you get the sense that this guy is incapable of saying these words because that would shatter one of the few beliefs he has – in himself. He doesn’t seem to have a complex idea of himself. So when I say I saw him as hapless, I mean that here is a guy who sells himself on his own ability to process a simple set of facts, but once he bungles his conclusions, he’s suddenly in the midst of this cultural and legal chaos that is impossible for him to retreat from. Because, to do so would be to shatter his own conception of who he is.

Morris:Yes, I think that’s a fair description.

Filmmaker: I might be giving him the benefit of the doubt.

Morris: Likewise. I don’t really have that firm a grasp of Fred, even having spent years with him. There’s something very slippery, something very elusive about him.

Filmmaker: And the movie’s quite canny in the way it plays with that, like the shots of him on the rock pile, oblivious to the ramifications of what he’s done.

Morris: Yes. I mean, I think that there’s this idea that filmmakers are social workers, which they’re not! At least I’m not. I’m grateful to Fred for participating in the film. Why he did it, I’m not altogether sure. Maybe he hoped for some kind of vindication, or maybe he just enjoyed the attention.

Filmmaker: Is that an important question to you, something that figures into your filmmaking process – why someone would agree to be in one of your films? Once you have the conception of the film in your mind, is the scrutinizing of your subjects’ motivations important or not?

Morris: I would say it’s inevitable. With Leuchter I thought about it often, because it was in a way a question of the whole movie: Why is he doing this? I believe that there’s this whole question about people who do bad things – do they know they’re bad, or do they think that they’re good? Have they construed themselves to themselves in such a way that they have convinced themselves that they are good and not evil? And in Leuchter’s case, he seems to me to be a person who believes in his own rectitude, in his own correctness.

Filmmaker: There’s something very American about that: the self-made man.

Morris: There’s something very human about it. Yes, I think there’s an American aspect to this story; I would not disagree with that. The idea of a self-made man, or a self-invented inventor, or crazy entrepreneur who finds a need and fills it. He sees that executions are taking place in the United States and says, “Aha, I can cash in on this!” But I think the problem is not an American one. Self-deception is not properly considered an ethnic problem!

Filmmaker: How much time did you spend with Leuchter over the course of making of the film?

Morris: Not that much. That’s what I’ve been trying to tell you. In the case of any of these people, not that much. Leuchter probably more than any other person in the past because I brought him back and reinterviewed him several times. And I asked him to participate in re-enactments. And I asked him for help with various issues so I could better understand what his position was.

Filmmaker: You screened an early version of the film at Sundance, and now there is this revised version. Talk to me about your editing process in constructing a film like this, because structurally, this film seems very, very clear. The film tells a story quite methodically; it is arranged in coherent sections. And yet I know that you worked on it for some time and went through different versions of the movie.

Morris: There are so many decisions being made when you’re putting a movie together. In this case, the major decision was whether to include voices other than Leuchter’s. Should we just hear Leuchter talking or interview other people as well? And I actually edited a version of the movie with Leuchter alone, and then felt the necessity of adding other voices in order to make two things absolutely clear: that he was wrong, and also to show the disparity of views about him, people’s general puzzlement.

Filmmaker: All of your films are funny to varying degrees. And there are moments in this film that are truly funny, but they are funny in their horrifyingness – Leuchter stumbling into a concentration camp looking like some American tourist with his wife on her honeymoon. At the screening I was at, there was some nervous laughter, and some people laughing out loud, and other people incapable of laughing. Is humor an unintended by-product of your stories, or are you consciously using it as a storyteller?

Morris: Humor is complicated, it’s not an ingredient that you actually put in something, like you add salt.

Filmmaker: Actually, in a lot of filmmaking, it is something you put in like adding salt. In a Hollywood film someone might say, “This scene doesn’t play. We need a laugh here.” And someone writes a joke.

Morris: I think a lot of the humor in my movies is absurdist humor. These are absurdist, surreal films among other things. And part of the humor, in this particular movie, derives from the utter disjunction between what Fred is talking about, or what he thinks he is talking about, and the reality of what he is talking about. His crazy capital punishment stories, his botched executions, the honeymoon in Auschwitz, which is utterly surreal, absurd and grotesque. And he is utterly unaware of this fact. Do I consciously make use of this sort of thing? Yes!

Filmmaker: You spoke earlier about creating monologues, but in this film there is also the formal device of the blackouts which punctuate Leuchter’s dialogues.

Morris: It’s something I started using in A Brief History of Time. In [that film] it had a kind of odd metaphorical character that to me, linked with that weird on/off clicking of Steven Hawking’s own communication and the possibility of him being “blacked out.” There was something about it that I liked – information being parceled out. Here it seemed to sort of capture the fragmentary way in which we know people, or know anything.

Filmmaker: Has there been feedback on this film from the revisionist history or neo-Nazi community?

Morris: I believe the movie has already been attacked in several places. This movie is certainly not intended to convince Holocaust deniers that the Holocaust happened. I don’t think anything could convince them. But I do think that it demolishes The Leuchter Report on it’s own level, on it’s own terms. Hapless Fred, as you call him, goes to Auschwitz. He takes these samples. He puts them in bags. He has them tested. Why doesn’t he find cyanide? We learn that the chambers might have been covered in plaster. He may not have the surfaces, [and testing for cyanide requires] surface tests. And he took the samples in such a way that they were horribly diluted. And [this is said by] the chemist who was hired by Leuchter to do the test. But why am I saying all of this? See, now I’ve been trapped into talking about [the film] in terms of the Holocaust! And that’s all because of you!