Back to selection

Back to selection

Extra Curricular

by Holly Willis

Messing With the Medium: On the Textured Pleasures of the Handmade Film

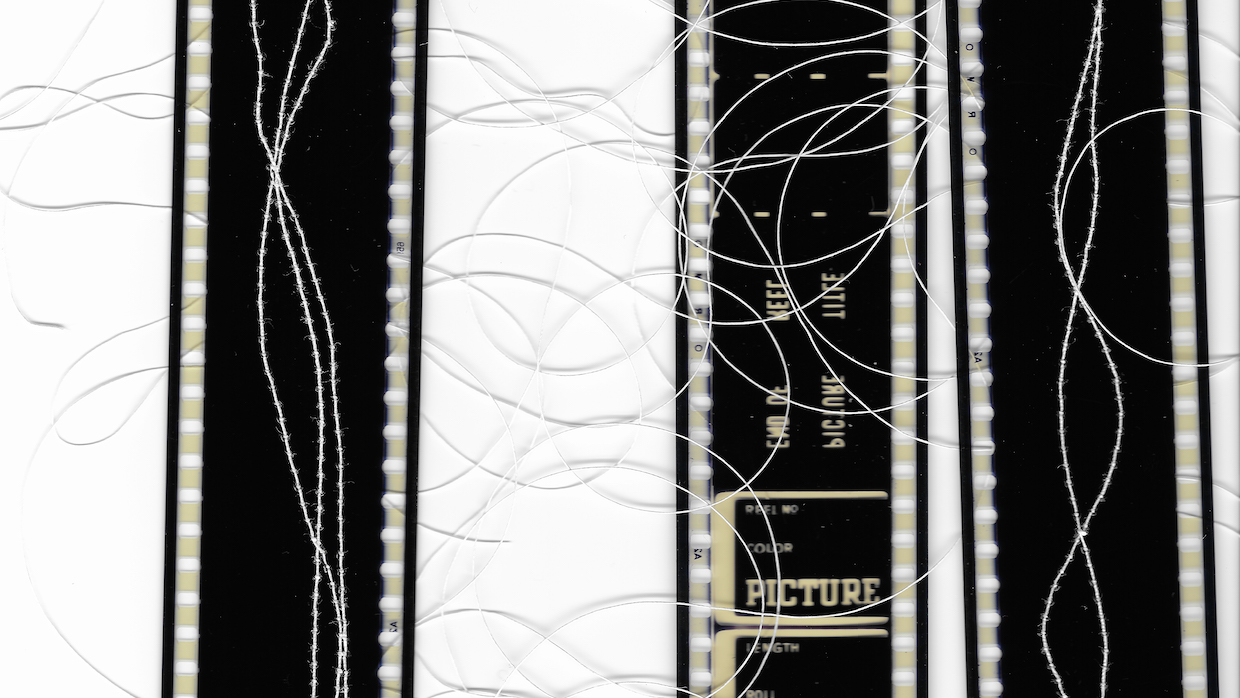

Three pieces of scratched film from Holly Willis's class

Three pieces of scratched film from Holly Willis's class Last summer, filmmaker Jennifer West and I were invited to talk at Femmebit, an LA-based triennial celebration of media made by women. I had been thinking about materiality and mediamaking practices, and Jennifer is known for a stunning body of work centered on physically manipulating strips of film. We decided to call our event “Messing With the Medium: Radical Materiality in Feminist Media” and challenged each other on stage in a battle of clips, each of us presenting a visual example of some sort of feminist creative intervention, along with a two-minute argument for its contributions to an expanded history of cinema. Our onstage clip slam was incredibly fun and made me not only want to showcase this rich body of work to students but also to revel in the making of such media.

With this exchange in mind, I created an undergrad class called “Handmade: Feminist Experimental Media Practices” for the spring 2020 semester in the Media Arts + Practice program in the School of Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California, where I teach. My colleagues in the Division of Animation and Digital Arts include handmade practices in courses dedicated to animation, but I wanted a slightly different approach. While my program focuses primarily on digital media, I knew there would be enough students to fill a class focused on more analog forms, and indeed, I’m working with a group of intrepid students who are cheerfully scratching emulsion and playing with light.

Fast forward to the present—February 2020—when Spanish filmmaker and scholar Albert Alcoz posted a query to the FrameWorks listserv, a longstanding email group dedicated to experimental film that was launched in 1995 by Pip Chodorov (who continues to moderate it with great generosity). Alcoz asked, “Does anyone know if cameraless film is a common subject at university?” He recognized that many alternative spaces host workshops dedicated to handmade filmmaking practices, but what about college programs?

The response was surprising. People wrote from around the world describing various classes dedicated explicitly to analog and cameraless filmmaking techniques.

Canadian film artist Lindsay McIntyre, who teaches “Analogue Practices” and an advanced version of the class in the Film + Screen Arts program at Emily Carr University of Art + Design, was among the respondents. McIntyre often makes her own emulsions and hand processes her films, and she has created a long list of extraordinary projects. She was recently featured on the cover of Inuit Art with a story by Taqralik Partridge. In another interview conducted for the magazine by Napatsi Folger, a quotation captures McIntyre’s focus on the hand in “handmade.” She says, “In media, there’s such a connection between your hand and your eye. It’s a really rewarding form to work in.” She continues, “I think, for me, it’s really important to have materials in my hands. If I’m sitting at a computer, typing and clicking in buttons and editing in that fashion, it’s not as satisfying a process for me.”

Other classes in this category include Charlotte Pryce’s “Alchemical Cinema” and “Devices of Illusion” in the School of Film/Video at California Institute of the Arts; Pryce has been investigating magic lanterns in her own work and is sharing their charm with students. In Greta Snider’s “Material Cinema” and “Media Archaeology” classes in the School of Cinema at San Francisco State University, students create some astonishing cameraless films. And the multiclass track called “Mediaworks: Animation, Documentary and Experimental Approaches to the Moving Image” at Evergreen State College includes the handmade. Faculty member and animation artist Ruth Hayes explains—on the FrameWorks list—“Students appreciate the materiality of working with film and photo processes, especially if all they’ve done before is digital. It’s also a way to get them into thinking about forms beyond the narrative and single-channel presentation.”

In addition to the surprising number of classes dedicated to handmade filmmaking, there’s also been a spate of recent book publications. These include Gregory Zinman’s brand new Making Images Move: Handmade Cinema and the Other Arts, which calls attention to the connection with painting in abstract, cameraless techniques; Reset the Apparatus! A Survey of the Photographic and the Filmic in Contemporary Art, edited by Edgar Lissel, Gabriele Jutz and Nina Jukić, which emerged from a three-year research project dedicated to exploring analog film and photographic practices; and Process Cinema: Handmade Film in the Digital Age, edited by Scott MacKenzie and Janine Marchessault, which was published last year. There are many more, and they point to an abiding interest in the handmade.

With my own class, I wanted to move in a slightly different direction. I am using as our conceptual foundation a body of work dubbed “new materialism,” which refers to a focus on matter as a significant component in framing how we act in and understand the world around us. Tenets of new materialism include the idea that matter is not inert but generative; that the fantasy of human mastery over matter has had catastrophic results on the world around us; and that humans and nonhumans are entangled in complex and compelling ways. Some of the reading here has included general approaches to craft as a feminist form of making, as well as headier concepts such as trans-corporeality as defined by Stacy Alaimo in Posthuman Glossary: “All creatures, as embodied beings, are intermeshed with the dynamic, material world, which crosses through them, transforms them, and is transformed by them.”

Given this, what does it mean to work with the materiality of film? How might cinema’s material support be leveraged to create alternative artworks and experiences? And how do our hands, and our bodies, participate in the cinematic apparatus in complex ways? As we transform film, how is it transforming us?

While there is a philosophical foundation that undergirds the class, I’ve tried to step away from the comfort zone of theory into the process of making and a kind of investigation through the handmade. We started with light, making cyanotypes and considering the work of artists such as Meghann Riepenhoff, who makes giant cyanotypes incorporating the interplay of the ocean’s waves. We moved on to projection, studying the incredible work in the 1970s of artists like Lis Rhodes, who created multiprojector environments; Barbara Hammer, who sought to completely reimagine cinema by undermining the centrality of the projector and bringing the bodies of the audience into the picture; and the more contemporary work of artists such as Sally Golding and Miwa Matreyek, whose performances feature projections onto their bodies. The students worked with projected light and shadow.

The next two sessions explored cameraless filmmaking techniques and the work of artists as varied as Carolee Schneemann, Ja’Tovia Gary, Naomi Uman, Jennifer Reeves, Jennifer West and Kelly Gallagher. We scratched on pieces of film stock given to us from the school’s archive from the lone extant reel of a film called Street Justice. Inspired by an amazing performance called “Reel Time” in 1972 by Annabel Nicolson, in which she used a sewing machine to punch holes on a strip of film until it disintegrated, I’ve been stitching on scenes from Street Justice, thinking about the continuities between the sewing machine and the projector (a topic also taken up by Prismáticas, an art collective founded by the Spanish artists Pilar Monsell and Aitziber Olaskoaga). When the film gets going at a good clip through the machine, I can see the characters in the scene begin to move. But more, there’s something thrilling about the physicality of the thread, the loops and the lines made down the long strip of celluloid.

In upcoming sessions, we’ll use toy cameras—the LomoKino, an old PixelVision that I’ve had since the ’90s, and the somewhat frightening Barbie Video Girl Doll, which is a Barbie with a video camera in the front, screen in the back. We’ll dip into more electronic forms when we make TikToks, bend some circuits and create machinima pieces.

However, I’m most looking forward to the end of the semester, when we will be inspired by the work of Heidi Kumao, who teaches in Stamps School of Art & Design at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. She has created a series of “Cinema Machines.” Explaining her projects, Kumao writes, “In each tableau, a sabotaged household object is fitted with a zoetrope-like projecting mechanism and a set of photographic transparencies.” She continues, “Each hybridized projector fuses nineteenth century film technology and everyday objects to present a short, repeated loop of a simple gesture.” I’m hoping we, too, can make some “Cinema Machines,” cobbling together kinetic moving image devices.

It’s a lot to cover, and we’re moving quickly. Exploratory, collaborative and inquisitive rather than competitive and masterful, the class—I hope!—embraces practice and process, as well as embodied experience. We’re looking for serendipity and pleasure and, on occasion, wonder in our shared acts of messing with the medium.