Back to selection

Back to selection

Memoria, on the Collapse of Cinema (a Book Review)

Memoria

Memoria Memoria

Giovanni Marchini Camia and Annabel Brady-Brown, editors

Fireflies Press, 2021

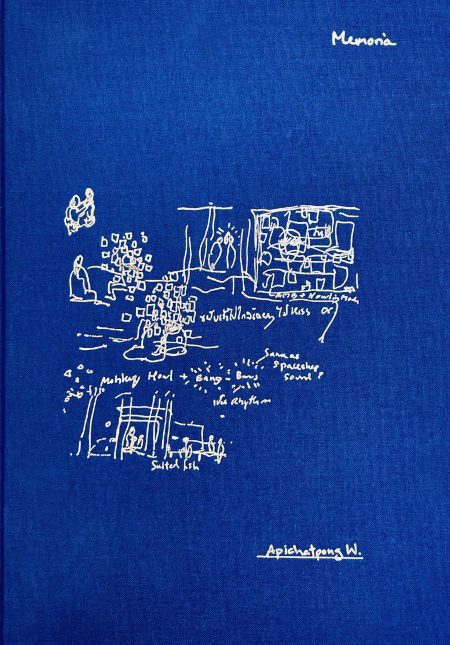

The book begins with the word “memoria” handwritten in gold on the blue cloth cover. The word appears again on the book’s first page, alone, black type on the white page, suggesting with its flourish of vowels a portmanteau of memory, history and cinema and calling to us from another language. “Memoria” is also the second word on the second page, just before the type slips into description: of glimmers, a window, boats, darkness, the cinema. There is a bang, a snap, and the snap of a picture, and we begin to sense how word, image, memory, page, the film frame and even the hand of the body that writes, draws and dreams all yearn to swirl into slipstream.

If this all feels inchoate, let me back up a bit: the book, Memoria, is a research notebook of sorts that collects the materials gathered by Thai director Apichatpong Weerasethakul in preparation for the making of his ninth feature film, also titled Memoria, which premiered in July 2021 at the Cannes Film Festival, where it won the Jury Prize; the film, slated for release in the US in October, stars Tilda Swinton as a woman visiting Colombia and inhabiting a peculiarly liminal space, not just of the traveler, but of someone caught between sound and silence, sleep and wakefulness, past and present. Someone, then, who is in and of the cinema.

The book is the most recent in a flurry of new releases from Fireflies Press, a seven-year-old independent book publisher established and run by Annabel Brady-Brown and Giovanni Marchini Camia (who is also a Filmmaker Magazine contributor). With the press, the pair has announced a commitment to art cinema as well as creative critical writing and has already published a plethora of delightful books that attend to forms of prose that move beyond both the academic essay and traditional film criticism. With Memoria, they have taken a step even further and created a beautiful, compelling and meticulously designed book that sits in relation to the film of its title, but also offers a poignant experience all on its own.

In the book’s opening pages, Weerasethakul introduces the book and its central trope, namely the “bang” that for a long time erupted in his body near dawn just prior to waking. He notes that the phenomenon is called “Exploding Head Syndrome,” adding, “It feels like someone snapping a rubber band inside your skull.” He goes on to describe the rhythm and tone of the sound, and how it eventually became a sonic companion that “emerged at sunrise and prompted me to listen to the sound of the city.” The bang will continue to punctuate the book, appearing over and over in the many sketches made by the director imagining the scenes he will shoot later.

We then move into the first major section of the book, which is a carefully constructed collage of materials that includes photographs, snippets from a treatment, sketches, notes and letters. Nothing is labeled, and indeed, there aren’t even page numbers and the handwritten notes move in and out of differing languages; we’re invited to sift through the material and to figure things out, but without any assurance of full comprehension. The images reinforce central visual motifs, of windows and doorways, as well as circles and hallways. There is also a sense of layering and of repetition, and an uncanny sense that you’ve seen the image or read a phrase before. Someone – somewhere – says, “Again and again, I’m struck by déjà vu.” Me, too!

The notes in the first part of the book chronicle a broad array of topics. There’s a section on “Tired Mountain Syndrome,” which occurs mountains are exhausted by underground detonations. There’s mention of another syndrome known as “Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory” in which people have painfully accurate and detailed recall of too much information. We begin to sense that it is not just the filmmaker who is suffering the effects of a strange hallucinatory state, but that the earth itself has been pushed to a limit and skewed; we’re all part of a larger sense of collapse.

Here, we also read the fascinating account of Eduardo, owner of a derelict cinema who suffered two near-death experiences that are described in crisp and haunting detail and include the memory of a projector, a bridge, a loud bang, and broken bones. In reference to this account of the cinema-owner, Weerasethakul summarizes: “I want to collapse fact and fiction, past and present. The sound of a bridge collapse, the sound in my head. A woman who hears sound, cinema… the collapse of cinema, of time, of persona.” This statement might be read as the driving force for the entire movie, it seems.

The next section presents a version of the shooting script, replete with handwritten notes and sketches, and interspersed with images from the film shoot. Again, there’s a sense of care in the organization; we begin with the first image of Jessica, the protagonist, looking out a window; this image abuts the first page of the script that describes the image. The movement between typed pages and images becomes quite fluid, and again, there is attention to visual motifs – so many windows!– and material from behind-the-scenes.

The third main section features an interview with Tilda Swinton from October 2019, which is yet another delight. At one point she is asked about her sense of the collaborative process with Weerasethakul, and she responds, “I am really interested in the frame, in quite a nerdy way.” She continues, “Professional actors often think they are the most important thing in the frame. I never think that. Very often it’s the window, or the chair, or the stream.”

The fourth and final section of the book presents a full diary written from the set by the eloquent Camia, from Memoria’s first day of production in August, 2019, through Day 42 in October, the same year. This personal account brings all of the previous material into a temporary constellation as we move day-by-day through the making of the movie. Reading these collaged fragments, one gleans a sense of growing coherence, even as that orderliness quickly slips away, moving between the “facts” of the film shoot to the “fiction” of what’s occurring on screen. Further, Camia’s voice is so personal and provocative; he’s an astute and curious observer. At one point when the crew shoots at Pontificia Universidad Javeriana on a Sunday, for example, when the campus is unusually empty, Camia writes, “The sound recordist Raúl, who usually fluctuates between registers of despair, has never looked this happy.”

Camia also highlights moments when he recognizes a particular element of Weerasethakul’s practice. For example, he charts the evolution of a particular scene as it shifts and changes during the day, noting that this emergent creativity is characteristic of the filmmaker’s methodology. “He isn’t bound to his original intentions and will usually start from a more elaborate premise that he gradually distils to its essential elements,” Camia explains. This section brings another very clear voice into the material, and provides a pleasing perspective.

I have not seen Memoria the film, so Memoria the book is not yet anchored to any particular source. Instead, it floats, a compendium of materials in full swirl that, in a practical way, offer a glimpse inside the workings of the mind that created the film. But more than that, impractically perhaps, it points to Weerasethakul’s dedication to a radically different modality for viewing the world. This view is present in his body of work, to be sure, but somehow in this book, it feels at once more present and more ephemeral. We begin to tunnel into his exploding head and what’s in there is verdant and strange, a kind of invisible vibration and resonance more than an identity or self. And of course, peering through a hole sounds an awful lot like peering into a camera, or looking at a screen. You see? It all circles back and around, déjà vu, again and again.