Back to selection

Back to selection

Visions du Réel 2022: Nuclear Power Plants and Lacanian Robots

Burial

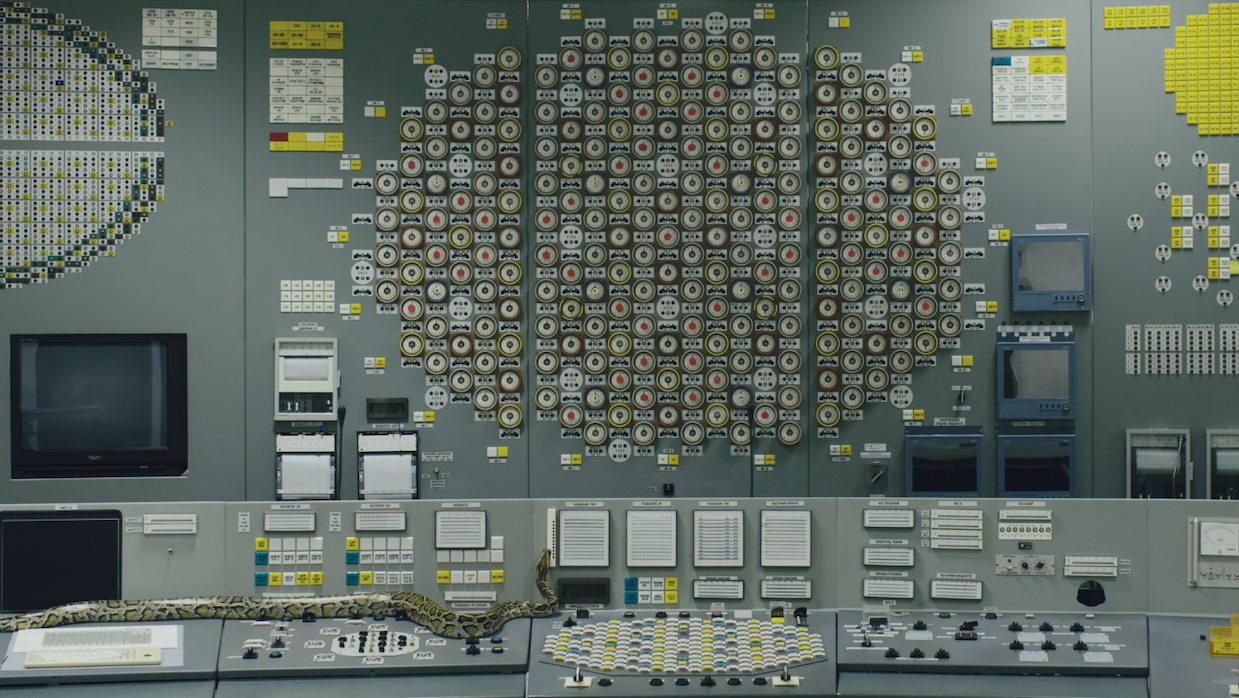

Burial With no conscious motivation, I was repeatedly drawn to films about Russia and the USSR’s former satellite states while sifting through this year’s Visions du Réel. The most formidable, Emilija Škarnulytė’s Burial, visually maximalizes the inherently spectacular structures of nuclear power plants. A sparse clutch of title cards contextualize the Ignalina Nuclear Power Plant (INPP)—built as an equally large sister to Chernobyl, its decommissioning and dismantling now a requirement for Lithuania’s entrance into the EU. The cavernous interiors slowly being broken down include, most captivatingly, a control room wall scanned in a three-minute, smoothly sustained right-to-left dolly, its nodes, buttons, meters and other constituent parts as pleasingly laid out as a Mondrian. The motion is hypnotic, while the soundtrack layers the ambiently indistinct chattering of dozens of scientists and workers—a lowkey, spookily effective conjuring of ghostly Cold War vibes, sonically closer to the opening of “Last Night I Dreamt That Somebody Loved Me” than you’d reasonably expect—over Gaute Barlindhaug’s beautifully gloomy, mildly glitchy electronic score. Elsewhere, drones are used to both capture a swimmer’s slow path through a body of water from a fixed gaze high above and to zoom around exterior wire towers. In grey-heavy black-and-white, the drone makes this real-world structure look like it’s overlaid on a wireframe rendering of itself—as close to realizing Tron in the material world as I could hope for.

A more innocuous afterlife of Cold-War-science-as-pageantry is a recurring thread in Aren Malakyan and Vahagn Khachatryan’s first feature together, 5 Dreamers and a Horse. Title notwithstanding, there are actually four main characters (plus, as promised, an equine; perhaps the fifth is Armenia itself or something equally abstract). That thread belongs to Melanya, who manually operates an elevator at a hospital and immediately reveals herself as a dream doc protagonist. Her job is an anachronism whose days are clearly numbered, and Melanya thoroughly enjoys every remaining minute. The mobile workspace is large enough to accommodate a desk at elevator rear and a large bench; during downtime, space-obsessed Melanya hooks up a small monitor, watches old documentaries about cosmonauts and speculates conspiratorially with a colleague about what really happened to Yuri Gagarin. Her slow response times piss off some doctors, but she’s a consistently endearing comic presence; the elevator’s rectangular confines, meanwhile, provide an ideal proscenium for the camera, placed at the correct spot for maximum symmetricity. Malakyan and Khachatryan’s other subjects are shyer but equally sympathetic: a young farmer looking for a bride (a tea-leaf reader tells him his future wife’s name will begin with a “Q”) and two queer teenagers whose default hangout zone is a safely isolated roof, where they can lightly flirt and show dismayed solidarity when watching videos of homophobic demonstrations. In cutting back and forth between storylines consistently captured in casually well-composed tableaux, 5 Dreamers’s selectively panoramic portrait of contemporary Armenia suggests a more benevolent Ulrich Seidl.

Assembled from unfathomable amounts of footage shot by USSR camerapeople from 1957 to 1991, Alexander Markov’s Red Africa reconstructs Soviet intervention in Africa, often positioned as attempts to build “solidarity” with the post-colonial continent. Working from largely silent raw material (literally hundreds of shooters are alphabetically listed in the end credits), Markov favors a flagrantly foleyed approach to historical reconstruction. The primary target audience is anyone who, for whatever misguided reason (guilty as charged!), might get a kick out of e.g. Leonid Brezhnev touring African countries, peering with great earnestness at every tree he’s shown. Reciprocal visits by African dignitaries are similarly rediscovered low-hanging fruit ripe for well-edited picking, like a montage of visitors being shown the wonders of the Soviet subway or, more overtly disastrously, the extremely racist ballet of Othello one’s taken to, complete with an eyerolling blackface Moor. All this is morbidly amusing enough on its own, with smaller specific points occasionally scored beyond “the USSR was comically inept at the optics of revolutionary support.” Unnervingly, there are scenes of children being taught how to fire automatic weapons, proving that today’s would-be freedom fighter is tomorrow’s already trained child soldier; footage of them on training break smoking Russian cigarettes underscores that the visitors accelerated the progression of nicotine addiction. The larger thrust, underscored by newsreel maps of further-flung points of the Soviet Union’s republics, is that a country which forcefully annexed others was in no credible position to tutor freedom: A final montage skips decades ahead, breaking with state-sanctioned celluloid for VHS-captured protests fueling exit demands as the USSR crumbled, unambiguously scored to Russian band Avia’s “Song of Thunderous Joy.”

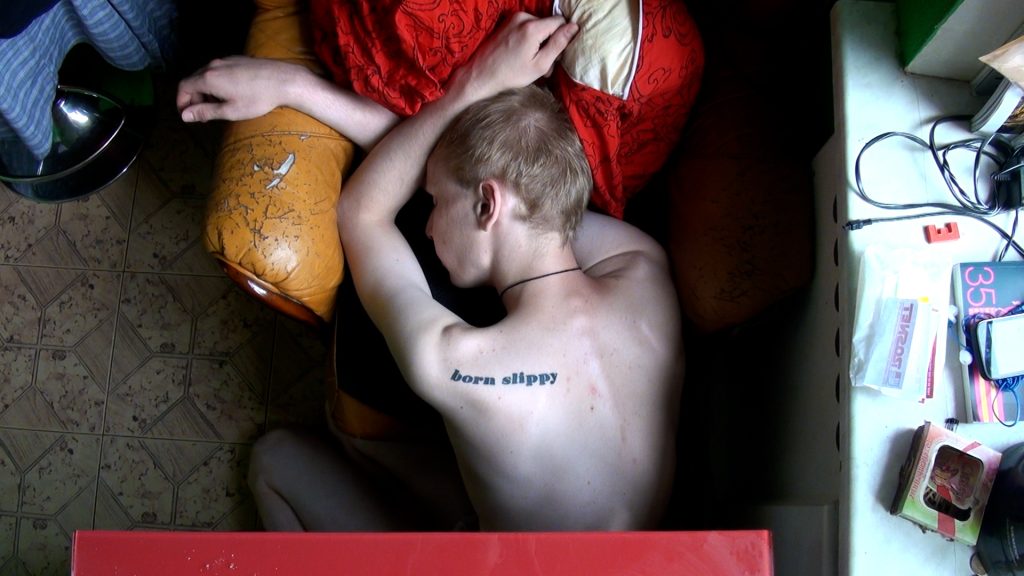

Marusya Syroechkovskaya’s How to Save a Dead Friend engages directly with the Putin-shaped present. Primarily constructed from footage Syroechkovskaya shot between 2005 and 2016, Friend demonstrates how far we’ve come since Jonathan Caouette assembling of Tarnation exclusively from home movie archives was a breakthrough. Now, any compulsive self-documenter can spend years filming, then decide which life thread to extract for their first film—which is not to diss Syroechkovskaya, a disciplined shooter from her teen years onwards. Friend focuses on her relationship with Kimi—first a BFF, then her spouse, his fate established in both the film’s title and an opening scene of his funeral. Because of its more recent origins, Syroechkovskaya’s archive is higher-res than Caouette’s; she and Kimi marvel at how good one of her new cameras is and, in the press kit, she breaks down gear with endearing precision (“I used to shoot videos on Canon Digital IXUS 40. The image size was ridiculous, 640 x 480 pixels. […] I had a short fling with Canon EOS 550D”). That’s one of three statements Syroechkovskaya has in the press kit, along with an “artistic statement” and a “personal statement,” which says she fled Russia and stands with Ukraine.1 Putin hovers over the film’s decade-plus both in New Year’s Eve addresses to the nation and recurring imagery of various police officers kicking ass at large. Attempts to tie his smothering ambience to Kimi’s spiral into hardcore addiction seem forced; as with many addiction narratives, this one’s sadly and gruelingly familiar without the imposed political gravitas, devoting pretty much precisely half the running time to repeated relapses and rehab stints. Its opening half is nonetheless winningly, unfamiliarly specific, a mid-aughts teenagerdom spent in the Russian grunge scene, loving Kurt Cobain and playing in bands that kind of sound like Slowdive.

Wang Chun-hong’s feature debut, Far Away Eyes, also stars its director, this time in situations that seem mostly constructed. This is a very familiar type of slow cinema made primarily out of prolonged, meticulously composed static shots, with a thematic focus on urban anomie and Chun-hong as a (mostly) unspeaking, inexpressive central onscreen presence. With scenes of characters dwarfed by gigantic billboards or staring at them from construction sites, it’s very clear Chun-hong is intensely familiar with his Taiwanese New Wave reference points, with a particular emphasis on Edward Yang’s The Terrorizers specifically and Tsai Ming-liang generally. For the opening stretch, I questioned whether we really need yet another of these films—the genre that shaped me most is perpetually on the verge of seeming totally tapped-out. The plot is a flimsy, familiar thing: Chun-hong is freshly single, alone, mopey, looking like Elia Suleiman without any surrounding jokes and election cycle bad vibes coming from TVs and overheard electioneering. But the individual settings (including a delightfully filled-up flea market of a store) and characters are warmer and less severe than their antecedents, and Far Away won me over fast by being an exceptionally beautiful, unusually well-tuned iteration of this particular festival film subgenre. Chun-hong’s distinctive differences from his predecessors include shooting in unusually good-looking digital black-and-white, which defamiliarizes potentially overfamiliar images; an overhead shot of dozens of cars and mopeds waiting at a traffic light, which is all but missing Lee Kang-sheng standing in a sandwich board next to traffic (as in Stray Dogs), is entirely different when drained of color, creating a nightscape that unexpectedly made Far Away Eyes VdR’s second film to make me think of Tron.

One short I sampled was notable as the second I’ve seen this year on the exact same topic. The first, Jack Weisman and Gabriela Osio Vanden’s Nuisance Bear, I saw at this year’s True/False; the title of Annabelle Amoros’s Churchill, Polar Bear Town is even clearer about its subject. I preferred Nuisance, a compact under-ten minutes (which, per a filmmaker Q&A, may yet be expanded into a feature); Amoros’s medium-length film boasts equally nicely composed widescreen shots, but its perspective on the subject isn’t necessarily more incisive and the punchlines take longer to get to. It is, nonetheless, interesting that both films pretty much end with a shot of the exact same thing—the undeniably fascinating sight of an unconscious polar bear being airlifted out of town—taken from more or less the exact same vantage point. Dueling nonfiction projects aren’t terribly rare, but this may be the first time I’ve seen two within three months of each other, let alone two that end with the same, obvious (right) choice.

Two shorts took entirely different approaches to fair use. Roberto Fassone’s Pas seul was described in its VdR capsule as “born during the first wave of the pandemic,” which I assume means it assembles various internet k-holes explored according to no particular logic but bored whim during that time. At least I couldn’t determine any larger organizing logic at play, but that’s OK, especially since I didn’t expect a whole section to be devoted at this late date to hugely enjoyable clips (largely from Dig!), of vintage-era Anton Newcombe conducting himself with supreme arrogance while leading the Brian Jonestown Massacre. (The end credits include, a little plaintively, “PLEASE DON’T SUE ME.”) Where Fassone’s raw materials come from several different branches of interest, Paola Michaels’s Sad Machines sticks with robots walking, on treadmills, falling down etc.—the kind of creepy and depressing sentience that never fails to ruin my day whenever it shows up in my feeds. But Michaels turns my nightmare into something surprisingly sympathetic by assigning voiceovers to the robots, read out through text generators, in which their anxiety about falling down, failure and self-improvement repeatedly return to Lacan; the initial incongruity, and then unexpected appropriateness of the train of thought, is as comical as intended.

My favorite of the shorts, Stéphanie Roland’s The Empty Sphere, begins with black-and-white images of what (I think is) a comet breaking up as it enters the atmosphere. As its entrance trail breaks up, a multinational group of observers cheers in lingua franca English, a heartening moment of global camaraderie prompted by an unexpected source. The rest of the 20-minute short’s first half tracks workers at a gleamingly all-white facility assembling a large device (space telescope?) preparatory to launching it into space. When the POV switches to a camera’s descent, the film abruptly switches to color for its descent from the atmosphere to deep into the ocean. This vertiginous and extremely attenuated plunge is a disorienting, entirely post-human gaze, something genuinely new I haven’t seen before.

1. Additional Ukraine notes: both Burial and Škarnulytė’s other short at VdR, Aphotic Zone, ended with a “We stand with Ukraine” card. Meanwhile, How to Save a Dead Friend’s press kit is extremely clear, stating both “Country of Origin: Sweden / Norway / France / Germany *” and “*No Russian government funding was used for this film.” ↩