Back to selection

Back to selection

“I Tried to Make the Film So Everyone Can Find Their Own Bowie”: Brett Morgen on Moonage Daydream

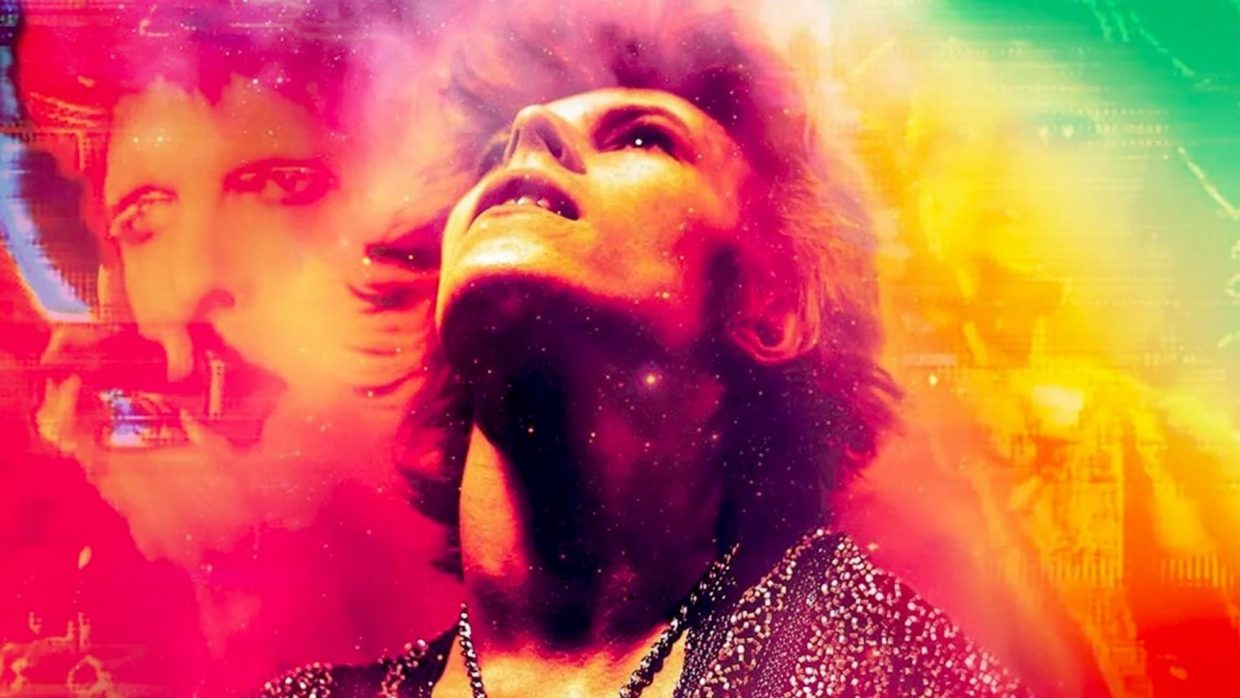

Moonage Daydream

Moonage Daydream Documentary innovator Brett Morgen once again pushes the boundaries of creative non-fiction filmmaking with his latest doc, Moonage Daydream. Morgen was given access by the artist’s estate to over five million works in the archive — music, film clips, artwork, musings, interviews, photographs and recordings, some of which have never before been seen or heard. The resulting two hour and 20 minute-long film is a kinetic, sometimes euphoric tribute to Bowie and his multitude of stage personalities, career offshoots, and personal reflections. As with his other archive-based work (Jane, Cobain: Montage of Heck), Morgen’s approach is unconventional. Utilizing some of the alternative forms of production that Bowie himself used – such as the multi-layering of contrasting tracks for his 1977 song “Sound and Vision” – Morgen creates an experiential musical journey that interweaves different time periods of the musician’s life (although Morgen states it for the most part the film stays in chronological order, barring the the film’s beginning and a few other moments). He steers clear of biopic staples like talking-head interviews and explanatory detail, opting instead for an often kaleidoscopic presentation that mixes and matches audio and video source materials.

With a gripping emotional throughline, Moonage Daydream had an overwhelming effect on me. For Morgen, the film was both a cathartic experience as well as an aid to his own recovery from a heart attack in 2017.

At Sheffield Doc/Fest where the film opened the festival last June, I sat down with the prolific director, writer and producer and had the opportunity to ask him about his inspirations and processes in making this beautiful work of art. Moonage Daydream opens tomorrow from NEON in cinemas and IMAX theaters in the U.S.

Filmmaker: This film immersed me in David Bowie’s world much more than I imagined. What inspired you to create an intimate montage of such an iconic artist?

Morgen: I was interested in moving away from biography, and [David] Bowie perfectly lent himself to this experiment. Going back to The Kid Stays in the Picture [Morgen’s 2002 documentary about film producer Robert Evans], I try to make films not about the subject, but films that are the subject, that personify the subject. My number one rule for this film was “no facts and no learned information.” The best way to experience Bowie is to not explain but to just succumb. And so the film was put together very spontaneously, with a lot of techniques that Bowie employed. I wanted to arrive at something different, totally experiential. We all have our own Bowie – I tried to make the film so that everyone can find their own Bowie.

Filmmaker: How did that correlate with the life-affirming thread that runs throughout the film?

Morgen: When I was looking through the five million assets that were provided by Bowie’s estate, the throughline that I came across had to do with transience and chaos. His musings were incredible – that’s what spoke to me. When we make these films, they are time stamps of the moment that we are creating them, not of the time that we are depicting. Chinatown is not about 1939, it’s about 1975. If I had done Moonage [Daydream] in 2015, there is no chance it would have felt anything like this in terms of [being] life-affirming. That is what I was open and receptive to.

Filmmaker: Was this life-affirming element influenced by your heart attack in 2017?

Morgen: I had my heart attack on January 5 in 2017. Moonage started in 2015, and Jane started soon after. Somehow the story has been presented as “this film gave me the heart attack.” My whole life gave me a heart attack. This film provided me with the recovery. When you last met with me to talk about Jane, we didn’t tell anyone about it because it limits your work options. What’s happened between now and then is the script for Moonage Daydream, which was written a year and a half after my heart attack. And yes, it was entirely influenced and impacted by that experience. When we were going to Cannes, I realized there was no way I could talk about this film without talking about the heart attack. I also feel that heart disease is a real thing in the film industry, particularly for directors. No one wants to talk about it because they want work. And I feel I am at a point in my career where I can still get work. So I feel a responsibility to address it.

Filmmaker: This also correlates with how you worked on the film over the course of the pandemic?

Morgen: Yes, it’s very much a piece of pandemic art. There were two things about the pandemic that were critical to the process. One, I was isolated from the world, which allowed me the time and space to focus which was wonderful. Two, I was making a film about finding ways to be creative during moments of isolation and alienation. It was such a mirror to what I was experiencing in this oppressive period of time. But I was also embarking on one of the most creative experiences of my life. So that wasn’t lost on me. I am sure there are aspects of the film that speak to the moment we were living through.

Filmmaker: Let’s go to the start of the filmmaking process. How do you begin?

Morgen: When I work on an archival project, I try and grab every bit of media that exists on the subject. In this case, the archive material amounted to five million assets. We then did a global search for everything else we could find. My team organized the material chronologically, and I started the screening process. With Montage of Heck, it took me two months. With this film, it was two years! We had budgeted for four months of screening time, so we blew our entire budget getting everything digitized.

Screening the material is like watching elevated television. I immerse myself, and make notes on how different moments make me feel. At the end of this process, I can usually extrapolate the script in two or three days. With Moonage, nothing happened. There was no collaborator I could turn to. We had no money to hire anyone. So it took me eight months to craft the code – to figure out how to write an experience that is not entirely narratively driven.

Filmmaker: You can very much feel this experiential quality from the moment the film starts. Can you talk about how you put together this collage-like viewing experience?

Morgen: The first 20 minutes you are not supposed to understand [the film], it’s supposed to wash over you and be a mystery. Once you get past this 20 minutes, you can relax. Ultimately, you can extract whatever meaning you want from it. We spend so much time in documentaries trying to make an argument – it’s difficult to trust that not everything has to be understood or explained.

There is one scene for example in Moonage that was a series of happy accidents. The scene was assembled in one hour. I had ordered dailies for Sam Bayer’s music video for the song, “The Heart’s Filthy Lesson.” I was really excited to watch it because it was a 35mm negative that had not been watched in 20 years. To make the viewing experience more exciting, I thought I would throw a piece of music over the footage. But I had just heard a cool interview from outtakes where David is talking about the mystery of art. I thought, I’ll throw that on. It’s perfectly synchronised to the music. It required almost no editing. I have not ever made a film being that careless.

I heard for years about Bowie’s legendary Berlin years. He threw everything he knew about songwriting away. Instead, he sent people into the recording room, let them do something different, and then he patched it together. I remember thinking, “There is no way this track is going to go with that track.” I had access to the stems – it’s all true. He put very different tracks together, and suddenly it’s [the 1977 song] “Sound and Vision,” so that’s what I tried to do.

Filmmaker: The scenes that integrate D.A. Pennebaker’s 1979 film Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars are incredible, with a mix of vibrant colors and sound. How did you create those sequences?

Morgen: I mostly used outtakes from Pennebaker’s film Ziggy Stardust [and the Spiders From Mars], and in some scenes we used it as our source audio. [Photographer] Mick Rock had a vast collection of MOS material. So in some sequences I integrated the two. The coloring of the photographs is not meant to make the shots feel fluid – it’s meant to be the opposite, almost like a patch-work. As a kid, I remember Pennebaker’s film being red and grainy and out of focus, but I always felt Ziggy was about color. So to bring Ziggy to life, I called my photo editor and asked him not to do anything to the photographs. And when I saw it, I thought, “Whoa, we need to go 180 degrees from there and bring more colors to the palette than what the footage is allowing us.” On top of that, some shots were from science fiction films such as 2001: A Space Odyssey because we were taking David’s cues on Ziggy’s Spaceman. When [photographer] Mick Rock asked Bowie about Ziggy Stardust three months before the film came out, he surmised, “It’s a gas – I just say space, and ray gun, and then it’s going to fill in the blanks.” So these sequences are my attempt to fill in the blanks. The sound design is super aggressive and has no bearing on what you see. There are machine guns, helicopters, and all sorts of noise that are meant to evoke feeling. I think it feels right in its finished form.

Filmmaker: Tell me about the process of building the audio out of Bowie’s tracks.

Morgen: I had a bit of fun with the audience for the first 20 minutes. I cue up a few “Space Oddity” notes, then some “Life on Mars?” notes. It’s like you’re going to get the Pet Shop Boys remix. I call it a jukebox musical – the film starts with a playlist that, in my interpretation, included songs that relate to transience, chaos and fluidity. But really, I don’t know about music more than anyone else. These are simply music tracks from my playlists. With all of my films, I have not had interference from artists when it comes to music. And I generally don’t work with a music supervisor.

Filmmaker: How important were his lyrics when deciding which track went over which scene?

Morgen: I don’t know lyrics to any song. I cheated. I had the lyrics sheets, the book that explains what the songs are about — the idiots guide to Bowie. So my playlist had the lyrics of the story I wanted to tell, but I assumed no one was going to get that. To me, subtext is an Easter egg. If anyone picks up on it, that is awesome. Subtext provides a cohesiveness, but it’s an anomaly in non-fiction. Direct cinema or cinema verité doesn’t generally provide for mise-en-scène.

Filmmaker: How important was chronology to you? Can you talk about how you came up with the film’s non-linear format?

Morgen: I wanted to set the tone at the start that we were not going linear, and that we could go wherever we wanted to go. So at the start, I have a song that was from later in his life, and I have a quote from Nietzsche that was from the last thing he did creatively. It was put there because I wanted to make sure it augmented the theme for the audience. And more importantly, when you open a film with a quote from Nietzsche and God, it sets you up for a different experience. It was a real challenge that haunted me – how do I prepare an audience to see a film that they think is going to be a documentary about David Bowie, yet it’s not going to provide them with regular biographical information? If you see this film expecting a straight documentary, you will be terribly disappointed.

Filmmaker: Tell me about your post process.

Morgen: I had just started editing on January 20, right before the pandemic started. I had brought in Academy Award-winning editor Bob Murawski, who co-edited The Hurt Locker. I was going to give him morsels of stuff to cut, even though I had done all of the screening myself. Then the pandemic came upon us. Because of my heart condition, I couldn’t be around anyone else. We also had to cut off the building, and we couldn’t take the media outside of our office, per the estate. So I had to go on my own at that point. Around March 2021, we started the sound design, together with Bowie’s long-time collaborator and music producer Tony Visconti and Academy Award-winning sound mixers Paul Massey and David Giammarco. And in August of this year, we started the color grade, finishing before Cannes.

I like to have a tremendous amount of control. When you are creating sounds that have nothing to do with the picture, you have to be present to drive that. So with Moonage, we did around 500 hours of color. The company [Company 3] kept trying to schedule unsupervised sessions. I was like, “I am not going to pay to have someone in there without me.” The sound team would tell me, “We’re just doing pre-dubs, you don’t need to be in here today.” Why would I not want to be on the sound stage, it’s the greatest place on Earth to be! I just want to be a part of everything. I don’t know how to do it any other way. I have to present the experience, which has to be designed, manipulated, controlled and constructed.

Filmmaker: A family question. Why is his second wife, Iman, featured in the film but other members of his family, including, filmmaker Duncan Jones, are not?

Morgen: Because it’s not a biography. Iman is included because I felt the need to put her in, it was integral to the film’s throughline. But I knew by putting her in people would ask questions why I didn’t include this or that from the family. I invited that criticism. With Montage of Heck, people asked why Dave Grohl wasn’t featured. A friend said you need to put Dave Grohl in because if you don’t, you are going to be asked about it. And sure enough, every interview people asked about it.

Filmmaker: Did the Bowie estate give you any limitations in terms of music or footage?

Morgen: I had no limitations. The estate never requested anything other than I make the film my own. At the beginning of the project, they said: “David is not here to authorize or approve what you are doing, so this isn’t going to be David Bowie on David Bowie. It’s going to be Brett Morgen on David Bowie. You need to make it your own.” When they saw the film, there were a few things they mentioned they wished were not in there, but I didn’t take it out. And they didn’t ask me to take them out. They are very happy with what I have made.

Filmmaker: Now with your producer hat on, did you have to fight to get this seen theatrically in cinemas and IMAX, which is an unusual feat for a documentary.

Morgen: This film is an interesting case study. It was financed in 2015 – think of the world we were living in then. There were only a handful of streamers. The Weinstein Company is still a huge distributor. Several distributors don’t exist anymore. So in 2015, my financiers insisted that we sell the SVOD to cover 50% of the budget. We did a deal with HBO with a six-month window as a silent partner – they gave us some money for it, and they have a small license on the film.

Fast forward to when we are going to sell the film in 2022. The money in non-fiction is not centered around theatrical. Right now as a documentarian if you are doing a high-profile musical film, you can sell to a streamer for money that was unheard of five years ago, or you can take an advance from a theatrical distributor. So because we had pre-sold to HBO, that eliminated a number of the streamers because they wanted all rights. Some streamers put in bids on territories, and then said we couldn’t go theatrical on those territories. It was so complicated to secure a global theatrical launch and to get investors to sign off on turning down more guaranteed money for that.

IMAX has been so supportive, they agreed to give us a day-and-date launch. Since 2015, I saw the potential revenue that we could have made come up here and then come back down over here. I had to be willing to walk away from a rather large pay day. In the end, it doesn’t matter. The most important thing for me was to present this film theatrically and on IMAX screens. However we got here, I am so thankful. It’s beyond a dream. As an independent filmmaker – this doesn’t happen to us.

Filmmaker: What are you plans following the release of this film?

Morgen: I learned from Bowie the art of challenging yourself. And so with the next film I am working on, I told myself I need to mix things up. I am doing a portrait of an iconic actor who has a very rich mythology around him. When I first sold the film several years ago, I imagined I was going to do one of these archival films where I create the mythology. But I called the actor and proposed that we do a cinema verité film where I follow him from the moment he gets a script to the moment he is on set. I will go home with him and wake up with him. I am going to approach it like a Frederick Wiseman film. I said to him, “It’s going to be terrifying to you, and terrifying to me. Most of the subjects in my films are either not alive, or I don’t interact with much when making the film.” But I said we need to do it because of Bowie.

Filmmaker: And is he up for the challenge?

Morgen: Fortunately he is a big Bowie fan and he is a fan of this film. It helped make the case. I am waiting to hear which production we will piggy back.

Filmmaker: Bowie would be very pleased.

Morgen: It’s incredible how David Bowie has impacted my life as a father, as a filmmaker, as a person dealing with anxiety. He was one of the most famous musicians in the world, and he would try acting, dancing, painting, sculpting. He put himself out there – that is what it’s about. For him, it was about the experience. To see how one informs the other. He would talk about how he would paint when he would get blocked with his music.

I hope in unexpected ways people can take something from the film and apply it to their own life situation. One reviewer said, “If you ever have writer’s block, you should put this film on, because David tells you everything you need to know.”