Back to selection

Back to selection

“We Aren’t Simply Trying to Appeal to Nostalgia”: Jon Bois on the Art of Sports Docs

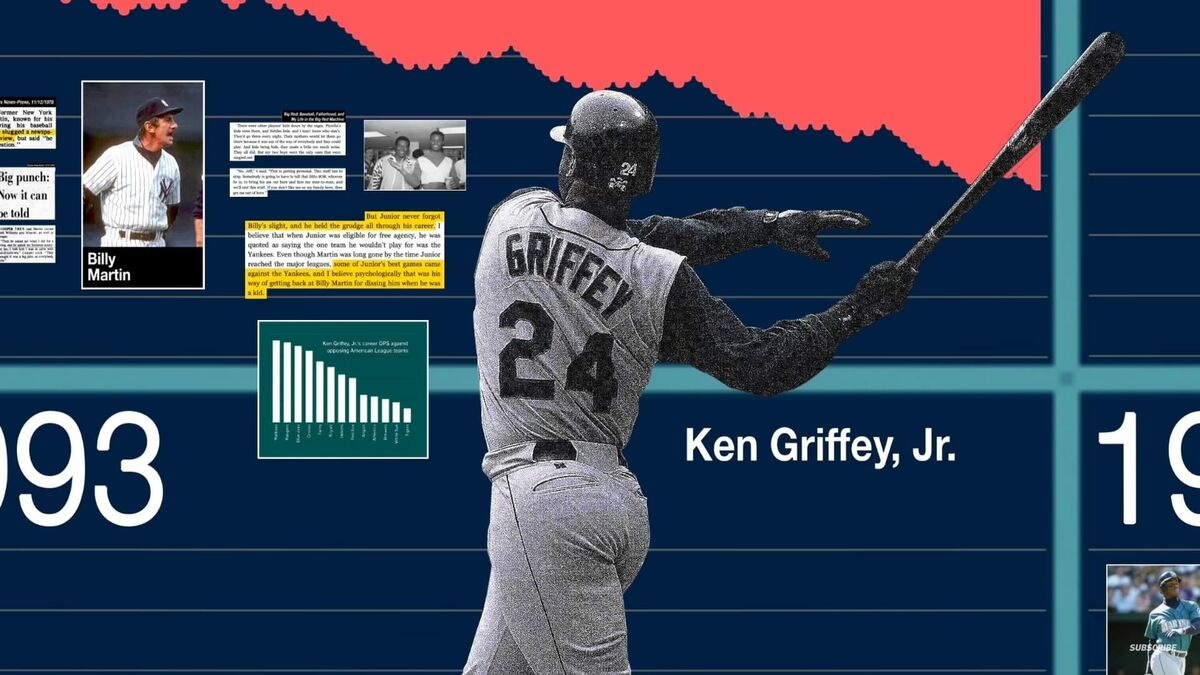

The History of the Seattle Mariners

The History of the Seattle Mariners Over the past eight years, Jon Bois has become a key pioneer of documentaries made for the internet. As the creative director of Secret Base, the YouTube channel of sports blog network SB Nation, his work across three series—Pretty Good, Chart Party and now Dorktown, co-written by Alex Rubenstein—takes often unconventional and lesser-known sports stories as a jumping-off point for increasingly ambitious, deftly handled portraits of some of Americana’s most crucial mainstays. By focusing equally on the minutiae of statistics, the highs and lows of a game and the many human dramas within sports teams and the cities surrounding them, Bois and Rubenstein establish a potent investment in the narratives that they craft, finding continuity and suspense in what might otherwise come across as the arbitrary nature of a career or season.

Paired with this attention to narrative construction is Bois’s facility as a director, crafting a distinct aesthetic through a combination of voiceover, Muzak, stock footage and a form of animation generated by placing images and charts in Google Maps and virtually flying around them. These abstract spaces become loci of both familiarity and surprise, the emotional tenor of a moment often determined by a sudden appearance of a visual element that would be mundane in any other circumstance but whose meaning is made clear by Bois and Rubenstein’s pre-established context.

While Bois and Rubenstein’s work has been deservedly feted since at least their first major Dorktown series, The History of the Seattle Mariners in 2020, it wasn’t until the second half of 2022 that they began referring to their projects as films, with two features that vividly represent two extremes of their craft. The first was Section 1, a fleet 42-minute piece that covers the events of a single date, December 19, 1976, where significant loss of life during a lopsided Baltimore Colts-Pittsburgh Steelers game due to deranged fan Donald Kroner—whose attempt to buzz the stadium ended with his airplane crashing into the stands—was avoided. The film emphasizes the urgency of the situation and the heroism and sports prowess of both teams. In contrast, The People You’re Paying to Be in Shorts, co-written and narrated by Seth Rosenthal and Kofie Yeboah, is a sprawling two-and-a-half-hour saga chronicling the 2011-12 Charlotte Bobcats, the worst team in NBA history despite being owned by the one and only Michael Jordan, which unfolds in arguably the funniest and most absurd video Bois has ever made. Both amply capture the peculiar and singular skill, joy and pathos of one of the most exciting documentary filmmakers working today.

Over the past few months, I had the great pleasure of interviewing Bois about these two films via email.

Filmmaker: Since at least 2019, your videos, especially in the large-scale Dorktown series that have produced some of your most acclaimed projects, have routinely (and correctly) been cited as fully-fledged cinematic works. What prompted you and the Dorktown team to finally begin calling them films, with Section 1 and now The People You’re Paying to Be in Shorts?

Bois: We’re really honored that people think of them as films, but at the same time, I’d understand anyone who thinks they aren’t. Dorktown features lack a lot of things that virtually all films have in common, the funniest of which is that neither Alex nor myself ever even pick up a camera. We don’t even know how to use a professional film camera. That seems like a pretty foundational component of what a film even is in the first place. So, while I did kind of quietly approach these things as films as I made them, proclaiming them to be films from the outset would have just felt silly. “Documentary” seemed less ridiculous and more accurate. But people did begin describing them as films, they were logged as films on sites like Letterboxd and, before long, it seemed that the consensus was that, yep, these were films! I think the audience is the best judge of that, so that’s good enough for me.

Once I realized I could call them “films” without anyone getting mad at me, you’d better believe I opted right into that. It’s fun, but it also kind of lets us dress for the job we want. We’ve held theater screenings for a couple of our documentaries, and I’d love for us to do some more of that. We’d also love to produce something on an over-the-top streaming platform someday. But regardless of what does and doesn’t happen, whether or not they’re considered films is far less important to me than the opportunity to make documentaries that we enjoy making and people enjoy watching. No amount of prestige can compare to that.

Filmmaker: In Section 1 and Shorts, there are two dramatic breaks with the featureless Google Maps backgrounds and archival footage that comprise the main visual images in your films: the recreation of Kroner’s airplane POV and the inclusion of what looks to be footage actually shot in Charlotte during the opening credits. Could you talk about the conceptualization of those inclusions?

Bois: The footage of Charlotte used in the opening credits of Shorts was made up of a few pieces of licensed stock footage from around town. It was sort of inspired by the opening credits of older shows like WKRP in Cincinnati. It seemed like fun to try to extract this story aesthetically from its timeline, which is also why I almost exclusively used catalog music from the ’70s.

The Kroner POV sequence is actually an inverse of that idea, come to think of it. The events of Section 1 took place in 1976, well before me, Alex or most people who watched it were born. All we really have in terms of original assets are blurry 4:3 tape recordings and poorly photocopied, grainy photos of the plane wreckage in the stands. The idea of pairing those visuals with the modern look of Google Earth computer graphics helped us to unmoor the drama from the year 1976 and put us in the moment—at least, that’s what I hope it does.

Everything about that sequence, from shooting it to coordinating it in real life with the events of the game, made it by far the most complicated thing Alex and I have ever attempted. We still bring it up every so often just to laugh about it. First, I tried the best I could to build a realistic 3D model of the since-demolished Memorial Stadium based on some blueprints I found—it was pretty simplistic, but the general dimensions were accurate and the solid blue color made it visible from miles off. It got the job done.

Then, I had to construct a timeline of Kroner’s flights as well as I could via details reported in newspaper stories, measuring the distances between the airports in question and estimating the probable speed of Kroner’s Piper Cherokee airplane. Google Earth has included a basic flight simulator function as a sort of Easter egg for a long time, and although I’d played with it some over the years, I’d never found a good reason to use it. Once we decided we were going to take this story on, I realized that this was probably the only chance I’d ever have to give it a try. Turns out it’s really hard to use a flight simulator with a keyboard—I probably had to practice for three or four hours before I actually felt like I was good enough to re-enact the whole flight. My steering’s a little rough in places, particularly right before the point of impact when it kind of bobs up and down, but I was fine with it. I just told myself that Kroner wasn’t exactly the best pilot either.

I think Alex’s end of it was the most impressive, though. In order to make this work in real time, Alex calculated the timestamp of each Colts and Steelers play as accurately as he possibly could down to the minute. This is laughably difficult to do, especially when your point of reference is a 45-year-old recording with commercial breaks edited out and some chunks of gameplay missing. We knew via newspaper reports that the game ended at 4:59 p.m. local time, so he just worked his way backward, estimating how much time had likely elapsed during commercial breaks, halftime and other missing footage. Since so much of his research ends up happening behind the scenes, I don’t think people fully realize how scary good Alex is at researching. I think he might be the best in the entire world of sports media, no joke. I checked in on his spreadsheet from time to time and saw how he’d reconcile the timestamps by adjusting a minute here, a minute there, over and over, in order to satisfy every potential conflict and get it as accurate as he possibly could. I think Congress could form an investigative committee on this game and still not get it any more right than he did. Unreal.

Filmmaker: I’m very intrigued by your mentions of aesthetic choices to bring your films out of the time period of their subject matter. Of course, in expansive series like The Bob Emergency or The History duology there’s no one year to get rooted in, but in projects that deal with these more concentrated timespans, what prompts you to try to find the drama in an in-between zone between 1976 (or 2011) and now?

Bois: It’s a lot of fun to subvert expectations, and I think people enjoy it when we take a creative tack that deviates from what they’re used to seeing in a sports documentary. More importantly, though, it’s our way of signaling that we aren’t simply trying to appeal to nostalgia.

If something like Section 1 resonates with someone for nostalgic reasons, that’s awesome—it was so rewarding to hear from people who watched those Colts and Steelers teams in the 1970s and enjoyed the chance to revisit guys like Terry Bradshaw and Bert Jones. But from the jump, we always engineer our projects for the enjoyment of people who never caught that chapter of history, or don’t watch football, or don’t even really watch sports in the first place. Understandably, we have to do a lot of work convincing someone like that that yes, this story is made for you too.

Building that case means doing a lot of the more obvious things, like briefly explaining how things like the NFL playoffs or the NBA draft lottery work, but also means doing more subtle things like paying special attention to how we score our projects. Our other shows like Beef History and Prism, for example, tend to use a lot of synthwave tracks, which always says to me, “This is not a sports story, this is a cool story.” I think things like those really matter.

Filmmaker: Could you talk about those music choices? Your videos early on were defined by your recurring use of royalty-free jazz music, but in these Dorktown videos you’ve opted for a wider variety of songs and anchored your videos less in familiar pieces like, say, “Love de Luxe,” “Flying Dragon” or “Style City.”

Bois: When I first started making videos with the Pretty Good series, I decided that while job one was just to do a good job selecting and telling a story, job two was to earmark them as something noticeably different from what people were used to. It’s definitely not enough for something to simply be weird or different for its own sake, but I hoped it would serve as a sort of hook—that if you saw a sports video scored with crusty easy-listening music, it might pique your curiosity enough to stick around and figure out what the hell is going on here.

That was the utility of those music selections, I guess, but the real reason was that I just love that shit. I have a love in particular for smooth, hyper-produced saxophone, from older stuff like Steely Dan and “The Captain of Her Heart” by Double, to newer stuff like Destroyer’s “Kaputt,” which I think is probably my favorite song. Our company affords us a license to the APM library, and when I first started poking around in it, I was blown away by just how much stuff there is in there. I’ve basically spent years crate-diving; it’s honestly one of the most fun parts of my job. I immediately became a fan of Keith Mansfield, who did stuff like “Style City” during his easy-listening phase, and weird electronica stuff like “Flying Dragon” from the legend Dieter Reith.

The idea of setting an on-base percentage chart to some smooth-jazz track called “Sex Man 1979” or something is hilarious to me, so I still do that from time to time, but I have tried to shift gears. Even now, I find incredible stuff in the library that feels like it’s been completely forgotten. I came across this absolutely gorgeous album by Alberto Baldan Bembo, released in Italy in the 1970s. I got the feeling that no actual human being had listened to it in decades, but it was just incredible. At the time, Alex and I had just barely started our Dave Stieb project. We were really just gathering notes—we didn’t have anything close to a script or an outline yet. But even at that point, I was 100% positive I was going to use “Oblo'” as the opening theme.

Pretty much the exact same thing happened with Shorts—I stumbled upon Roland Kovac’s album Helena and was instantly positive that it was going to define the sound of the project. Sometimes I love a track so much that it really does take center stage, to the extent that we write around it. There have been times I’ve asked Alex, “Do you have another 50 words or so you could add here? I gotta let this song play.”

Filmmaker: How do you and Alex (and, for Shorts, Seth and Kofie) work out the production schedule for the films between writing and image production/editing, especially as pertains to structure?

Bois: Typically, Alex and I will informally decide on a project a couple of months before we actually greenlight it and begin production full-time. During that phase, we’ll use whatever spare time we have to do research, take notes, build out some charts and piece together some kind of script outline (which we usually end up changing entirely as research goes along). This allows us to stress-test the story and make sure it’s something we find compelling and can have a lot of fun with. Once we do, we meet up with our managing editor at Secret Base, Ryan Nanni, and executive producer Will Buikema, and if we all like what we’ve got, we move forward with it.

A crucial part of that stage is sketching out a rough idea of what we call the “boss chart.” Basically, it’s a big elaborate chart (or template) that serves as a Christmas tree on which we can hang all the other charts, photos, newspaper clippings, etc. For Falcons it was the giant falcon that illustrated the franchise’s win/loss differential, for Stieb it was a baseball card and for Section 1 it was the football field and play-by-play timeline. Since probably 98 percent of a Dorktown video lives inside its CGI world, it’s crucial to lay it all out and arrange it in an interesting way that’s going to serve the purpose of our narrative. Often times, I’ll build out that chart before we even start writing the script. It makes it so much easier to confidently write the script if we know what it’s going to look like and where those words are going to live.

Once we do get going full-time, Alex and I have put in so many reps by this point that we have a pretty solid idea of how long a given project will take us. It all comes together in tandem—we’ll write a couple of script segments, design charts and arrange assets for those segments, then move on to the next chunk of script. It’s probably a pretty unusual order of operations, but it’s so nice to be able to test out some camera angles, pans and zooms as we’re writing the lines. For example, if I have a chunk of narration that I realize is going to drag too long onscreen, I’ll know right then and there that I need to either condense or cut that piece of script, or add some more things to look at. Or—and I’ve used this cheap trick many times—just move the camera slower. Once the script is finished and all the assets are built out, it always feels like the hardest part is over. The shooting and editing that come next take a lot of time, but at least all the toughest calls have already been made.

Filmmaker: Could you talk about the general intent behind many of those camera moves? For an illustrative example, in the Dwight Howard/Chris Paul draft charts early in Shorts, you shoot them mostly in push-ins and push-outs, with the exception of a “crane”-down and up, right before the newspaper clipping in the Howard chart. Towards the end, you move to a slanted angle that captures both Paul and Felton in the second chart, which is kept during the move back to the Howard chart, before rotating out to the frontal angle again as you zoom out to the win-loss charts. Even in these very imprecise terms, there’s an elegance that doesn’t call attention to itself but always remains dynamic, and I was wondering how you implement them in your films.

Bois: A big advantage of our visual format is that we can call back to previous elements in a cool way. At the same time, we tend to throw a lot of different but similar-looking stuff at the viewer, so I like to avoid as much confusion as possible. Whenever I call back to a photo or a story clipping that the viewer’s already seen, I like to situate the camera at an isometric angle. Hopefully, this evokes the idea of glancing back, rather than looking directly at. This is my way of trying to flag it for the viewer like, “Yeah, you saw that already.” I also like to lean into the three-dimensional nature of the world whenever it makes sense to do so, just to establish the feeling that we aren’t looking at a big slideshow—we’re flying around in a virtual world, however basic it might be.

One lesson I’ve learned over the course of our projects is a pretty obvious one: the sharper the angle, the more you sacrifice information for “looking cool.” It’s basically a direct trade-off. To take a shot toward the end of Shorts, for example: right before the final draft lottery shot is revealed, the camera flies in tight behind the Bobcats’ bar in the bar chart, with the Bobcats’ season schedule in the background. There’s zero information that can actually be drawn from this shot, so in that sense it’s meaningless. But shots like this one look cool to me, and by obscuring the charts’ meaning it helps me to digest the most fundamentally concrete things you could possibly look at in an abstract way. This is a really corny way to put it, but hey, why not: if you look at a chart straight-on, you can see what it means. But if you take a step back like this and look at them all from a distance, you can see how they feel.

Filmmaker: Speaking of feeling, how much does tone factor into yours and Alex’s early-stage production process? Whether it’s the steady tension of Section 1 or the hilarious roundelay of Shorts (including the genuinely moving final validation of Jordan), these films feel defined by your approach to the material almost more so than the actual subject matter. Even something as simple as the constant use of “Mike” feels inseparable by the end, I’d also love to know when you came up with that and the direct addresses generally.

Bois: Shorts is a great case study for this, because we knew we wanted to have some fun with this one. We’d recently finished working on Stieb, a fundamentally bittersweet story rife with sports agony, and Section 1, with which we had to take a more serious tone since the story was a matter of life and death. While there was plenty of funny stuff in Mariners and Falcons, we’d never really tried a feature-length comedy, which used to be my lane—before I started making video, I mostly wrote goofy stuff. At the very outset of Shorts, I really wanted to take the opportunity to get back to that, especially since Alex and I were bringing Seth and Kofie aboard. The four of us had literally spent years laughing at those Bobcats, so it was pretty obviously going to be a comedy.

Very early on, I did something I’d never done before and created a basic mood board for the version of MJ we saw in this story.

The beleaguered wisdom and pure tiredness of Jack Arnold, the over-meddling and incompetence of Gil, Henry Hill firmly in his “egg noodles and ketchup” era and H.I. McDunnough at the end of Raising Arizona, an idealist still unable to stop dreaming about the best possible world despite all available evidence.

It took me multiple failed efforts to figure out the comedic device I wanted to use with Michael Jordan. At first I had the idea of simply framing him as an “area businessman and basketball enthusiast” without ever mentioning his NBA career but pretty quickly ditched it, because it felt too mid and too annoying to sustain across an entire documentary. Then I thought about reading from the imagined diary of Michael Jordan during this 2011-12 season, but after running it by our legal team, I found that unless I really threaded the needle, it could put us at risk for misappropriation/defamation issues. That was just as well, because after trying to write it out a little, I nixed the idea anyway. There were plenty of critiques I wanted to make, and if I tried to write things as I thought Jordan might see them, that would have been off the table.

I finally decided to throw myself into the ambiguous role of Michael Jordan’s annoying lackey. I couldn’t recall a single documentary in which the narrator addressed the subject directly without actually having access to that subject. It was a very “I’m not touching you, can’t get mad” framing device that I found funny, but also appropriate.

I loved The Last Dance. I think having such extraordinary access to personalities and video assets can be a blessing or a curse, but in that case it was very much the former. It was compelling, funny, artfully structured and wall-to-wall entertaining even for people who don’t consider themselves basketball fans. It’s hard to imagine doing a better job than they did. At the same time, the mere fact that Jordan participated meant that many things would go unsaid, although they did a great job allowing his pettiness to seep through.

Secret Base’s lack of direct access is another “blessing or a curse” sort of deal, but I think it really works in our favor. We never have to worry about saying or showing anything that might displease our subject matter. That allowed me to treat Michael Jordan not as a demigod, not as a guy who could halt production at any given moment, but as just a guy—a person with ambitions, failings and disappointments, just like the rest of us. Some might interpret Shorts as our effort to take him down a peg, but I actually feel like there’s a dignity in exploring how he, the person, might be feeling about all of this.

I decided to address him as “Mike” because that’s how he introduced himself to me and to millions of others via his “Be Like Mike” campaign that ran while I was a little kid. It really came together once I found his primary photo. I was searching through the Getty archives and found this photo from 2011 that happened to catch him looking straight at the camera from across the court. He appears to be expressing such a wealth of emotions, depending on the context of the moment: he might be disappointed, or fatigued, or puzzled, or annoyed. It’s like…imagine being a little kid, and your parent gets home from a hard day of work, and you immediately run up to them and insist that they should buy a Ferrari because you just saw one in a magazine.

That’s the exact face they would make. That’s exactly the face I saw when I lobbied for Jordan to un-retire at age 48. It’s like he’s silently saying, “Just shut up. Please, for the love of God, just stop talking. Leave me alone.” Another component of this I personally found funny is the question of why, exactly, Jordan would put up with me hanging around him and peppering him with all these idiotic questions and observations. I love the trope of a character who’s inextricably linked to a sidekick who he doesn’t particularly like at all, but allows to hang around for reasons that can really only be guessed because it’s never explained.

Filmmaker: That mood board brings up a perhaps obvious if annoying question: are there specific documentary or narrative works that provide inspiration for your films? I know you’ve brought up, for example, Calvin & Hobbes in relation to 17776, but your occasional invocations of other media like Black Sunday in Section 1 makes me wonder if there are other examples.

Bois: This is weird, but I’ve taken more creative inspiration from video games than from any documentaries or films. I’ve played turn-based strategy games my whole life, ever since we installed Warlords on the family computer when I was eight years old. I still play a good amount of Civilization off and on. I love the top-down map view of those games because you can survey this grand overarching saga you’ve created, in the micro and macro scale, totally at your leisure. If someone else sat down and looked at the screen, they’d just see an arbitrary scattering of cities and pikemen and shit, but it all makes sense to you. You’ve seen it become what it’s become. I like to think the viewer gets a similar feeling when we zoom all the way out to behold the mess we’ve created.

To some degree or another I’ve taken inspiration from games across a lot of genres. The first Deus Ex, which I discovered right after graduating high school, is a big one. In the most basic sense it’s a first-person shooter, and if you played it in the most efficient, straightforward way without any objective but to complete the game, that’s probably how it feels. But the game is absolutely loaded with books you can pull off the shelves and read passages from; email conversations and arguments between people who you’ll otherwise never encounter in the game, but help to fill in the margins of the story; secret areas where you can have big long conversations with hidden characters. The sheer wealth of tertiary yet incredibly compelling material they scattered into that game just astounded me. Our wandering CGI format allows us to try to create those tangents without it feeling like we’re stopping the show—we can just peek over there for a minute or two, then move it along.

The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild is also pretty inspirational. It’s probably the closest thing to a perfect video game ever made. There have been tons of great open-world games, but this is the one I wanted to explore more than I wanted to conquer, or “beat,” or whatever. I found myself trying to up Link’s stamina not so I could take down some boss, but so I could scale some huge mountain I wanted to climb and see what was up there. I don’t think any of my projects quite capture that feeling in the visual sense. It inspires the narrative more than anything, specifically the cliche of enjoying the journey more than the conclusion. We often like to treat things like a big, pivotal game, as a conduit through which to understand stories and people, rather than just a referendum on a player’s or a team’s value.

Filmmaker: Even considering the difference between the media, do you try to strive to achieve some sort of interactivity akin to a video game on the part of the viewer? Aside from 17776 and its relatives, the most apparent example to me is still the incredible explanation of the rules of football with “alternative programming” in The Search for the Saddest Punt in the World, but I wonder if you seek to evoke it in other ways.

Bois: It’s very fun to try to infuse a feeling of interactivity into a strictly one-sided medium. We try to do that by speaking to the viewer rather than just talking about a thing in a disembodied way. Sometimes that means directly addressing the viewer as “you,” and other times that just means being diligent about writing every line for every kind of viewer there might be. That “alternative programming” bit was a fun gimmick that allowed me to sidebar with the football agnostic while also letting the football fans in the crowd know that I appreciated their patience.

It’s very uncommon for major documentaries to feature narrators who go on and on like Alex and I do. Many of the best ones don’t even have a central narrator at all; they’re just artfully woven together with accounts from various personalities, media clippings and firsthand footage. With this new wave of internet documentarians who take center stage as narrators, I think we’re seeing the realities of what you have to lean on when you don’t have much of anything in the way of access or budget. Your greatest asset is your personality and voice. Speaking for myself, I’m not a particularly extroverted guy. Generally, talking in front of a mic for hours isn’t something I’m naturally drawn to. But I realized from the outset that it was something I needed to develop and get comfortable with, because I didn’t really have a choice, and immediately I was surprised by how much I enjoyed it. Doing so offers us a unique ability to address the audience directly.

Vin Scully, the Dodgers broadcaster who passed away last year after calling games for 67 seasons, is a hero and inspiration to both Alex and myself. There have been many unforgettable broadcasting legends, but Vin was the greatest of all time, and I don’t think there’s any question about it. Many do this, but he did it best: when you listened to him call a game, you genuinely felt like he was talking to you. He had this superhuman ability to call a game all by himself, with no co-hosts, and literally never, ever make a mistake. Even past his 80th birthday, he was just razor-sharp with both his play calling and analysis, and he never slipped. But he would also take opportunities to entertain and put on a show for you. When the action died down, as often happens in baseball, he would take the chance to tell a fun story from a month ago or from 40 years ago. Sometimes he would build these riffs that almost resembled short one-man plays. When he did these things, he was telling you that he wasn’t here simply to broadcast, he was here to talk to you. He wanted you to have fun. We’re not Vin Scully and we never will be, but in terms of the ability to speak to the person on the other end, he’s a north star for us.

Filmmaker: How do you evoke Scully’s sense of riffing in your own work? It seems to me your tangents have gotten more built into the main thrust of the video—the way you interweave, say, Jordan’s free-throwing prowess into the Diop free-throw while setting that off as a mini change-of-pace is so integrated.

Bois: The Gana Diop free throw segment was a decade in the making. When it happened in 2012, I was a staff writer at SB Nation, and it inspired me to study the concept of the airballed free throw itself. I tried to dig up every known example, and I studied the tape to try to measure how badly each one was missed. My conclusion was that Diop’s airball was worse than any other free throw I was able to find. That’s one of a million stories I kept in my back pocket for years and years. A couple of years ago I dropped video of the shot in my team’s chat. Turned out, Kofie and Alex and Seth all had something to say about it. We just couldn’t stop laughing at it. I think that’s the moment we knew we wanted to tell the story of that team.

But it was even more fun to try to infuse some sort of purpose or meaning into that moment beyond “this team sucks.” It turned out to be the perfect opportunity. I knew Michael Jordan has perpetually had to swat away the instinct to un-retire, and this was objectively, without a doubt, the one thing he could have done better. He could have walked straight onto the floor in street clothes and swished that free thrown. That’s the one objective truth on which I built a mountain of bullshit. Of all the things I’ve ever done, that segment is one of the things I’m proudest of. The reason I think the Bernard Parmegiani horror music works there is that some small part of me, and maybe even the viewer, believed it might be true. You know it would be an awful idea for Mike to return to the court, but you realize you’re trying to talk yourself into the idea, and you realize that when Mike saw that airball, wherever he was, he was probably thinking about it.