Back to selection

Back to selection

Fantasia International Film Festival 2023: State of the Genre Nation

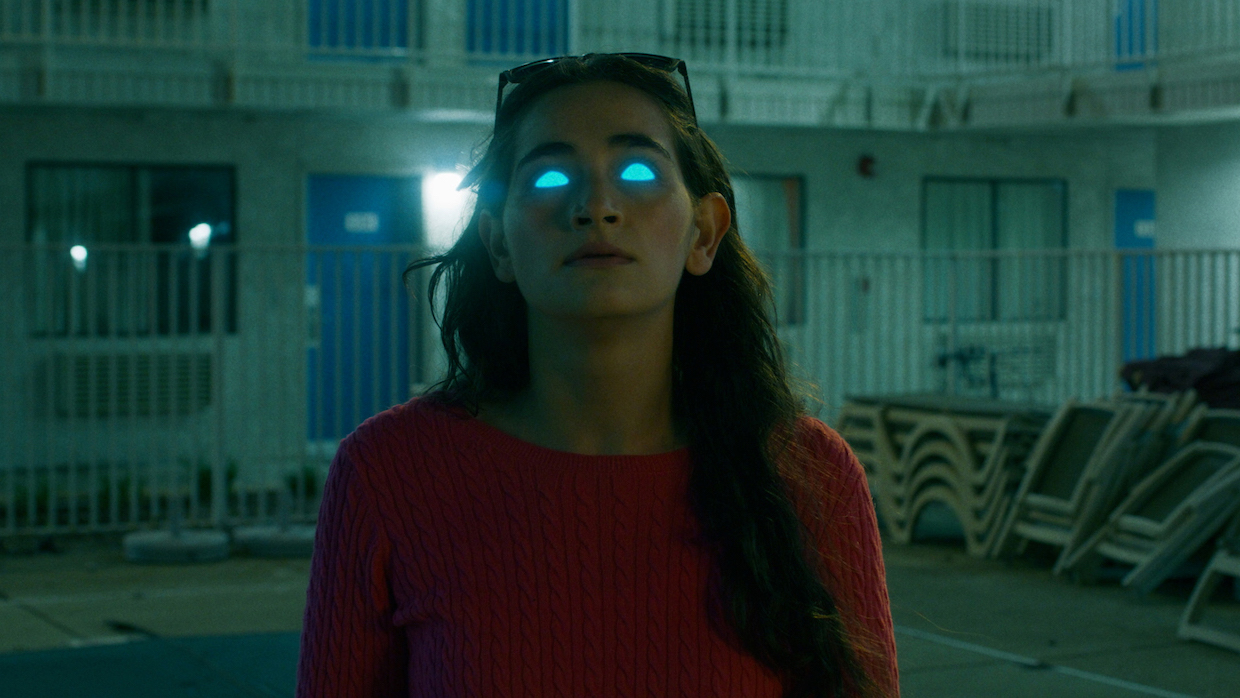

Isabel Alamin in The Becomers

Isabel Alamin in The Becomers The conclusion of Fantasia International Film Festival’s 27th edition brings the temptation to paint a “big picture overview” of the state of the film industry in general, in particular the genre community. The Montréal-based three-week event has never been about blinding star power (while Nicolas Cage was scheduled to be onhand to receive this year’s Cheval Noir Career Achievement Award, the actor had to cancel due to the ongoing SAG-AFTRA strikes), instead putting directors and audiences front and center. Like last year, a highly anticipated A24 horror release made an appearance just days before opening theatrically (last year Halina Reijn’s enjoyable Bodies Bodies Bodies, this year Danny and Michael Philippou’s excellent Talk to Me). Nonetheless, strikes and talks of a “hot labor summer” were still top of mind, not least due to news that the festival’s own workers were operating under untenable conditions; to the festival leadership’s credit, unionization appears imminent. As mega-conglomerates witness their streaming bubbles burst and battles are waged over transparency of viewership data and increased residuals for writers and performers, what does a director working in independent horror filmmaking have to look forward to?

Last year I wrote that “as theatrical play dwindles and distribution models continue to shift toward streaming (several of this year’s films will debut on AMC’s horror streamer, Shudder, later in the year; others, no doubt, would dream of doing so), the festival provides countless movies with a largely appreciative audience.” I was reminded of this while attending the world premiere of the new film from independent producer-turned-director Jenn Wexler, The Sacrifice Game, a film that had its distribution rights secured by Shudder before principal photography had even commenced.

Set in a boarding school for girls over the Christmas week of 1971, Wexler’s second feature is an invasion-meets-demonic-possession movie that sees a group of serial killers with strong Manson Family vibes forcibly enter the school and take a teacher (Chloë Levine) and two students (Madison Baines and Georgia Acken) who didn’t go home for the holidays hostage. The reason for the serial killers’ visit is hard to put into words, but I’ll try: the foursome—including, as the ringleader, Mena Massoud, clearly having a blast playing the extreme opposite of his title role in Guy Ritchie’s 2019 Aladdin—have been on a very specific, blood-spilling roadtrip, collecting pieces of flesh from victims who, for a reason not clear at the outset, have had ancient demonic symbols carved into their bodies (while strategically collecting flesh is not uncharted territory in popular dramaturgy, the most famous example wasn’t exactly someone who centered his schedule around Christmas). The group believes that the boarding school is the final piece of their epidermis-collecting puzzle, one that, upon completion, will give them unlimited otherworldy powers. But what if the demon is already hiding in plain sight?

Shot in Quebec in the spring of 2022, The Sacrifice Game is an amusingly bloody period piece that thankfully doesn’t choose to mimic the aesthetic of its hyperspecific time period. Yes, vintage clothing and black-and-white news coverage of Vietnam make their obligatory appearances, but Wexler and cinematographer Alexandre Bussière’s post-production team are wise to not litter the screen with Adobe Premiere Pro presets of faded colors, specks of dirt and intrusive changeover cues (i.e. “cigarette burns”). I also trust Wexler’s eye for spotting new talent; after her 2018 punk slasher, The Ranger, provided Jeremy Pope with his feature debut acting credit, who can say what potential might emerge here?

Booger, the debut feature from Texas-born, Brooklyn-based filmmaker Mary Dauterman was, much to my gratitude, not a film about sinus-related discharge but a merger of deliberately over-the-top body horror and a poignant portrait of grief and the digital traces that exist after a person passes away. As the film attests, the goofy TikToks and InstaStories we create with friends on a random summer day in the park or an evening out at the local pub can be an important piece of ephemera to help an individual come to terms with loss (in some instances, it can also stunt their ability to move forward, but I tabled my pessimism for the film’s duration). That’s certainly true in the case of Booger, the title character being a feline a roommate is tasked with caring for after her roommate dies in a freak biking accident.

Dauterman’s film is also about an extremely physical transformation, of Anna (Canadian actress Grace Glowicki, who attended McGill University, just a few blocks up from the Montréal film festival) and the cat characteristics she develops after being bitten by Booger. Following the injury, Anna finds herself uncontrollably devouring cans of cold cat food, lapping up liquids with her paw (sorry, hand), coughing up hairballs and taking a fatal chomp out of annoying rats in the street. It’s tough to lose your best friend, but it’s more than a minor inconvenience to transform into their pet.

I’ll admit that this aspect of the movie, while displaying a selfless performance by Glowicki—what physical lengths won’t she go to?!—kept me less than fully invested, partly due to my curmudgeonly belief that after you’ve experienced the Seth Brundlefly experience once, there are only so many ways to rework the intense awe and disgust derived from watching a performer get progressively grosser. But I will say this: while shot in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn (Decatur Street, Hancock Street, and, most notably, the area’s popular watering hole, Do or Die, are visible throughout), the film is unique in the way it doesn’t necessarily feel like a “New York movie,” eschewing the usual sights for some less traveled paths. I found myself oddly comforted whenever a character would drunkenly stumble past a public park with the “circled leaf” logo visible behind them. It’s also a film that makes expert use of (and finds pathos in) Rupert Holmes’s 1979 earworm, “Escape (The Piña Colada Song),” which is no small feat.

Shortly after the trailer for David Gordon Green’s Exorcist sequel dropped (but a week before the original’s director, William Friedkin, passed away), Sean Horlor and Steve J. Adams’s devil-centric documentary, Satan Wants You, made its Montréal premiere. The film chronicles the rise and subsequent debunking of Michelle Remembers, the 1980 nonfiction novel that detailed Michelle Smith’s recollection of the childhood abuse she suffered at the hands of demonic satanists masquerading as upstanding citizens. That she recounted these traumatic experiences to a psychiatrist (Lawrence Pazder) whom she then went on an endless media tour with, concluding with the two becoming husband and wife, is just one of the headscratching factoids this documentary covers, bringing in several talking heads (some of which were also featured in a 2014 retro report by The New York Times) to further express their disbelief.

Brief dramatizations depict the sessions between psychiatrist and patient; by keeping the camera at a distance and obscuring the actors’ faces and keeping them silent, the reenactments are less distracting than they could’ve been. The film is at its best breaking down if Michelle really remembered anything at all or was coaxed into believing so; I got the impression that the film feels that Michelle may not had been lying but that her memories were. The major goldmine for the directors are the scratchy but still chilling audio recordings from those sessions, here presented publicly for, I believe, the first time. And while it remains up for debate whether something happened to Michelle or any of the children involved in the Satanic Panic of the 1980s, in presenting a throughline from that Reagan-era hysteria to the rabid QAnon, “Save the Children” dumbfuckery of today, Satan Wants You’s subject remains topical.

Graeme Arnfield’s documentary Home Invasion, a feature-length amalgamation of a cine-essay, found-footage comedy, social critique, and text-heavy lecture, traces the history of the home doorbell. Arnfield digs deep into the origins and evolution of the apparatus, arriving at what we today know as the Ring bell, a camera device meant to alert homeowners of a foreign presence at their doorstep. In drawing a throughline from a seemingly innocuous invention to 21st-century community watchdog efforts like the Citizen app, Arnfield presents a compelling case for how the doorbell was always meant to be a gateway to larger mass surveillance efforts. There’s something equally funny (socially-awkward children ringing the bell looking for friends to play with, drunk idiots “performing” for the camera once it lights up and they know they’re being recorded, various forest animals wandering onto the porch in the afternoon) and uncomfortable (these technologies growing more Big Brother-like by surveilling the outside world from the comfort of their own home) about Arnfield’s presentation. In some respects, his film reminded me of Dmitrii Kalashnikov’s 2018 nonfiction whatzit, The Road Movie, equally inspiring shock, awe and a few chuckles; in Arnfield’s film, the anxiety is induced by its sociological implications. Described by its director as “made in bed during the pandemic,” it’s appropriate that the film is completely made up of footage from other people’s cameras—in making this film, the director has found yet another use for the doorbell.

So ensconced in the Chicago film scene that it arrives touting local filmmakers Joe Swanberg as a producer and Frank V. Ross in a supporting role, Little Sister director Zach Clark’s latest feature, The Becomers, is an otherworldly sci-fi romcom about extraterrestrial star-crossed lovers. In depicting two shape-shifting entities who arrive separately on Earth searching for their misplaced mate, Clark’s film provides his Midwest cast the opportunity to play alien visitors disguised as the humans they body-snatch along the way. It also gives the actors the opportunity to work without one of their key resources, their eyes—when the creature overtakes the body of a human, the host’s eyes glow a blinding neon color, something only sunglasses or contact lenses can mask. Toggling between a Jarmusch cool and a Linklater chill, the film doubles down on its hangout vibe by enlisting Russell Meal, one half of American sibling rock band Sparks, to serve as narrator. Once our alien protagonist overtakes the body of a woman who, along with her husband, have been up to treasonous deeds (it involves the kidnapping of a prominent Illinois political figure, played by local actor Keith Kelly in an oddly endearing performance), Clark’s film shifts into a different register, one less high-concept but more performance-driven and featuring no doubt the best use of a song by The Cry.

Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” makes a memorable appearance in John Rosman’s debut feature, New Life, which made its world premiere at Fantasia. Opening on a shot of a bloodied woman (Hayley Erin) suspiciously wandering into a suburban home to retrieve an engagement ring before fleeing as soon as gun-wielding law enforcement arrive on the scene, the first half of Rosman’s film deliberately withholds crucial narrative clues. Is this woman, Jessica, on the run? If so, from whom? Is she wanted for a crime? If so, for what? Once we’re informed that a group of federal agents are attempting to track Jessica down before she crosses the border into Canada—taking place in the Pacific Northwest and shot across Oregon, the film is filled with beautiful landscapes, endless forests, and very frigid weather—we at least know that we’re watching a “race against the clock” movie, although whether we should be rooting for the lead to get caught or for her to outrun her pursuers is initially and deliberately left unclear.

What I most appreciated about New Life was the sly way in which Rosman plays with familiar tropes and viewer expectations. Upon encountering Jessica, several characters, all reasonably well-meaning and generous with their resources, suspect what we all suspect—that she’s been the victim of domestic abuse and is attempting to get as far away as possible. However, through a series of fragmented flashbacks, we begin to understand that that isn’t quite the case. I also admired Rosman’s worthwhile choice to provide equal screen time and backstory to another female character, Elsa (Sonya Walger), the special agent assigned to hunt Jessica down. As if scouring the state for a fugitive wasn’t burdensome enough, the family-less Elsa is suffering from a debilitating case of ALS, her bodily functions shutting down at an alarming rate. What could have been just an oddly specific attempt to boost a shallow screenplay’s heft, bringing in the “horrors of everyday life” to balance out the film’s more genre-y attributes, turns out to provide the film with a surprisingly well-earned gutpunch of realism. Its inclusion feels incredibly lived in and personal and, as that Bob Dylan song which plays several times throughout the duration of the film, reminds us how it feels to be without a home like a complete unknown.