Back to selection

Back to selection

Via Chicago: Daniel Hymanson on His Documentary Debut So Late So Soon

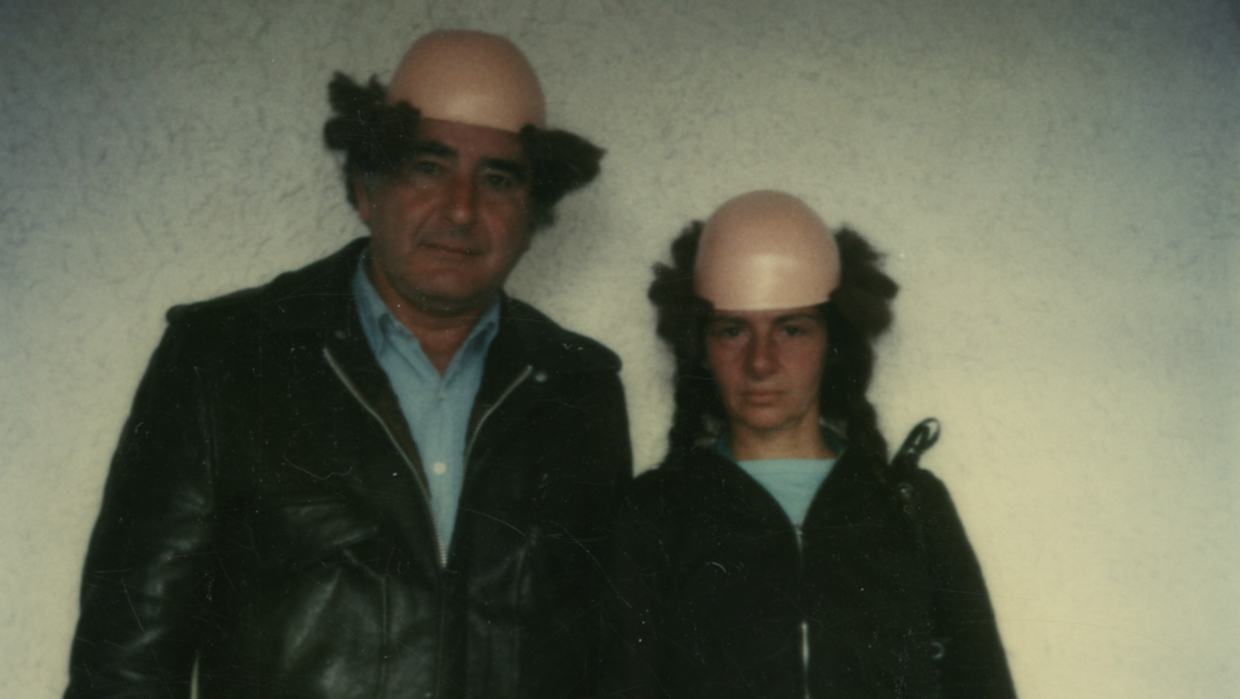

Don and Jackie Seiden, the subjects of So Late So Soon

Don and Jackie Seiden, the subjects of So Late So Soon Simultaneously a gentle portrait of two aging artists and an appreciative look at a bickering but loving couple, Daniel Hymanson’s debut feature, So Late So Soon, benefits from a level of access most documentarians would crave. Having known Chicago-based artists and educators Jackie and Don Seiden since he was a young boy, Hymanson sets himself and his camera inside the Seidens’s multi-storied, eye-catching home. Known locally as the Candyland House, the Barbie House and the Rainbow Cone Home, this Rogers Park residence has been occupied by the Seidens for close to 50 years, its interiors and exteriors closely resembling the creativity of its owners.

“Being old, being elderly, to me is like a really dirty trick….I just think it’s godawful,” Jackie admits at the midway point of Hymanson’s documentary. As Don continues to age rapidly and lose sense of his surroundings, eventually requesting that he, to the dismay of his wife, be placed in an elderly living facility, So Late So Soon doesn’t flinch from showing the brutal stress and frustration the marriage endures. Hymanson, many decades younger than his film’s subjects, acknowledges this decline while re-emphasizing the artistic spirit the couple possessed and, in many ways, continues to.

After its world premiere at the True/False Film Festival in 2020 and a theatrical release at the end of 2021, So Late So Soon is now available for rent and purchase on numerous VOD platforms via Oscilloscope Laboratories. A former 25 New Face of Independent Film, Hymanson recently spoke with me about the origins of the project, his experience taking the documentary through various film lab programs and why it’s always crucial to get a fresh pair of eyes on your material.

Filmmaker: You said in your 25 New Face profile that you received a mini-DV camcorder as a teen and went on to graduate from Wesleyan University with a degree in film studies. At what point did you go from being a cinephile to someone who wanted to pursue film production? And, knowing of the strong nonfiction scene in Chicago, when did you know that documentary filmmaking would be a gateway for you? Assuming that it was…

Hymanson: I’ve wanted to make films since I was very young, although I can’t recall something in particular inspiring that interest. I just remember being 11 or 12 years old and wanting to make movies. I got a little mini-DV camcorder when I was 12 or 13 and made a few documentaries at that age. For whatever reason, I was drawn towards nonfiction. I continued making short films throughout high school, then went to Wesleyan for film studies. After that, I knew I wanted to make a long-form nonfiction project and that I wanted to make it with, and about, Jackie Seiden. [As a young boy, Hymanson attended youth classes taught by Seiden at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.] Right after I graduated from college at the age of 22, I moved back to Chicago and Jackie and I started working together on what would evolve into So Late So Soon. And while this was the first project [that I would direct] after completing college, I had some experience working on other people’s films.

Filmmaker: Was the film studies major essentially non-production focused? Were there any production electives you took to gain additional experience?

Hymanson: There actually was a production component to the major, so I did gain some production experience in college as well.

Filmmaker: How did you get involved working on other directors’ films (as an associate producer and assistant editor on Sara Dosa’s The Last Season and as an associate producer on Bill and Turner Ross’s Western) before making your own?

Hymanson: Once I moved back to Chicago, I spent about six months conducting numerous interviews with Jackie (that I ultimately did not use in the final cut), editing a 60-minute version of the footage into a feature. While I was editing that footage, I reached out to a producer, Josh Penn (who would later come on to produce So Late So Soon), as I had seen a short he had produced at the time called Glory At Sea [directed by Benh Zeitlin]. Josh informed me that he was in San Francisco working on a documentary by Sara Dosa [The Last Season] and invited me to visit and work with him and Sara.

After production was completed, I wound up going to New Orleans to work with Josh and his company, The Department of Motion Pictures, on the Ross brothers’s Western. Throughout each of these experiences I was, of course, always thinking about what would become my film. The experience I gained from working with Sara and Josh and Bill and Turner and everyone at The Department of Motion Pictures was incredibly educational and certainly helped make it possible for me to eventually complete So Late So Soon.

Filmmaker: Those initial interviews you conducted with Jackie were, at this point, about ten years ago now?

Hymanson: Yeah.

Filmmaker: Was the initial plan for the film to be a series of interviews with Jackie and Don? Were you shooting off and on for a long time? What was the timeline like, from actually filming the interviews to finding the structure ?

Hymanson: I went into the project by interviewing Jackie, primarily about her artwork in their house and experience teaching over the years. Those were essentially the only things I knew about her, so that’s what I assumed the film would consist of. However, over the course of filming, I got closer to Jackie and Don. I then took the footage and, like I mentioned earlier, edited it into a 60-minute film, showed it to a few people, then took a step back.

Filmmaker: How did it go?

Hymanson: The film was totally incomprehensible. Not only that, but I felt like I didn’t show what was so special about spending time with them in that house.

During my subsequent period of stepping back a bit, I found myself watching a ton of documentaries to help me figure out what I was trying to make, as well as identify the types of films I was personally moved by. I was watching documentaries that I felt might be relevant to my project, so I watched Allan King’s work (including his 1967 documentary, Warrendale, and his 1969 documentary, A Married Couple), Terry Zwigoff’s documentaries about different kinds of artists (Crumb and Louie Bluie) and Ross McElwee’s Charleen, a documentary about the filmmaker’s former poetry teacher. What I observed in those films might seem obvious saying out loud, but those films are memorable partly because the filmmakers couldn’t have anticipated or planned in advance for what exactly would transpire. So, around 2013 or 2014, I asked Jackie and Don if I could come back and film them in a more observational way. This time I wanted to approach the film by being completely open to it evolving in ways I couldn’t anticipate.

Filmmaker: You obviously knew Jackie extremely well (and I imagine she was comfortable being in front of your camera), but how would you describe your relationship with Don? Had you been friendly with him before shooting? Don and Jackie are very different kinds of personalities, so I was curious if you took different approaches to filming each of them. In what ways does your approach change based on who you’re filming and reacting to?

Hymanson: Don was certainly a different kind of personality, it’s true, but I had known him from the time I was four or five and took an art class with Jackie. After that class, my family would periodically visit Jackie’s house, and on our visits, were introduced to Don. He was a very wise and kind man, “someone who gave off this feeling of knowing exactly who you were in a profound way. I was also in awe of his artwork. But yes, I had known Don since I was a kid and certainly grew to know him a lot better throughout production.

I don’t know if I shot Jackie and Don any differently. I mean, there would be discussions between the three of us about what the documentary was going to be like and what I was going to be filming, and I had discussions with them individually as well, but I don’t know if I had a very different way of filming them. Don was just a quieter presence, in some ways less active, so the filming may have been a bit more static there.

Filmmaker: Given their careers, Don and Jackie were used to being on camera. However, when you’re entering their home, their personal space, was it just as natural? Or did you have to arrive hours before filming to make them feel comfortable? Were there days during production where you would visit just to visit and not bring the camera with you?

Hymanson: Throughout the periods where I was regularly shooting the movie, we had a routine where I’d come by the house one or two times a week to shoot for a few hours, then the three of us would have dinner together. There was a lot of time during the five or so years where I wouldn’t bring a camera with me at all. But I also think that Jackie and Don’s relationship to the film (and what they thought of it) and my relationship to filming them changed over the course of those five years. There was a period where they asked me to stop shooting, so I paused for a few months. There were also periods where Jackie would call me to come over and record. Due to my shooting the film over such a long period of time, what we each thought about the film changed. The duration altered our relationship to the film.

Filmmaker: At what point did you first think about assembling a rough cut to submit to feedback labs? Were there certain goals you set for yourself as it pertained to having a cut ready by a certain deadline to submit to various programs?

Hymanson: I stopped filming the bulk of the movie by the end of 2017, only going back a couple of times for short periods after that. Most of the film is only from a few months of actual production, even though I shot over many years. The end result is, truthfully, primarily from just a few months in 2017.

Before then, I hadn’t edited any sort of rough cut. All I had were edited selections, short samples, to show a few people. I didn’t start editing the film in any real way until I began working with Isidore Bethel, who came aboard as editor of the final version. From there we put together a rough cut that was very collaborative and featured the input of our four producers: Trace Henderson, Josh Penn, Kellen Quinn and Noah Stahl. Isidore and I worked with them to edit and submit the film to Sundance’s 2018 Film Music and Sound Design Lab, the True/False & Catapult Film Fund Rough Cut Retreat and the Kartemquin Films Lab. Each of those experiences were incredibly helpful and changed what the film ended up becoming.

Filmmaker: In what ways did you find those experiences to be helpful to the film? Or even personally to yourself, as a filmmaker?

Hymanson: I had been working on the documentary for so long (and had known Jackie and Don for so long) that any outside perspective was helpful in sorting out how people who didn’t know them would perceive the footage. Isidore and our producers didn’t personally know Jackie or Don, but they had gotten to know them really well through all of the footage I had shot. So, those moments at the Rough Cut Lab, the Film Music and Sound Design Lab and the Kartemquin Films Lab were incredibly important in observing how other people saw the film with fresh eyes. Oftentimes their feedback would alter the way I viewed certain moments. Moments that I thought would play one kind of way wound up playing the complete opposite. You need to take a break for a bit, then get back to work on it.

Filmmaker: What was the Film Music and Sound Design Lab experience like? Music and the aural life of this film feel equally important.

Hymanson: It was an interesting experience, although not in the way [you might expect]. Although I was paired up with a great composer, Christy Carew, and loved what she composed for the film, by the end of the lab, the experience was most helpful in my making the decision that the film shouldn’t have a score.

I’m having trouble remembering the exact stage we were at when we came to that conclusion, but that’s what we decided on. Even so, there’s still a lot of music in the film, most of which comes diegetically from Jackie, as if the film is in a way “scored” by her and Don. There’s “Smooth Operator” playing at the beginning of the film, there’s the Wille Nelson song at the end. Jackie’s playing music throughout the film and when we’re shown her slideshows, etc. There was a lot of music inherently in the film, so when I tried to include original music in there it just didn’t live up to it. The music that’s already in the film is really good and anything I attempted would surely feel reductive. A score would push the film off in a certain direction and I think it worked best to not have one at all, except in the end credits where there’s some original music included.

Filmmaker: Much of Don and Jackie’s professional and personal background is shaded in by the archival footage you include. Some is local news coverage of their work from decades prior, while other clips are more private and relationship-driven. What was the process like of pulling and digitizing all of this material from what I can only imagine were a bunch of different sources? If it was costly, did you apply for any finishing funds to cover the expense?

Hymanson: Jackie and Don had a ton of boxes of Super 8 film and VHS and audio cassette tapes filled with material they had captured over the years. It was fun for me, personally, to go through it all and see them at an earlier stage in their lives, to observe the ways they had stayed the same and the ways they’d changed. On an aesthetic level, I think a lot of what they shot was quite beautiful and funny. Jackie carried an audio recorder around from 1979-1981 and you get to hear a little bit of that in our film, in an audio sequence we decided to include. I enjoyed listening to those more intimate conversations Don and Jackie had with one another and with different family members and friends.

The transferring and digitizing of all of this material was complicated. We had to go to a bunch of different places and I must admit that I don’t know these processes very well. I remember it often feeling like we would get some footage back [after the transfer] and something would be noticeably out of sync or there would be some error going on over the video footage. We’d then take the masters to a different place and they would transfer it and it would be fine. There was a lot of that. For anyone looking to transfer any form of tape media, there’s an amazing place in Chicago called Media Burn that archives tape media all the time. We worked with them on this film and also used a few different places (including the New York-based Metropolis Post) over the years for transferring different samples of the Super 8 material.

Filmmaker: Isidore isn’t based in the U.S. After that process concluded, did you have to work out a remote editing schedule?

Hymanson: Actually, no. When we were editing the film, Isidore was based in Paris, so I relocated there for the majority of the editing process, roughly two years in total. It was an incredible place to edit the film and Isidore and I worked together the entire time. Come to think of it, there wasn’t really any time throughout the edit that we were working remotely from one another.

Filmmaker: You enlisted Nice Dissolve, the indie digital post-production house in Bushwick, to be your DI facility. Was that for color grading purposes? Deliverables such as DCP creation and things of that nature?

Hymanson: Exactly. We worked with [Nice Dissolve owner] Pierce Varous on the final color grade and all the finishing deliverables. I just didn’t know anything about that stuff and it was my first time going through each of these processes, like color grading and sound mixing. It was all so new to me, but Pierce was very patient. It was an interesting yet difficult process, especially the color grading, which I found difficult at first but now really appreciate how the film looks and sounds.

Filmmaker: It was a difficult, painstaking process? Did it change what you had envisioned in your head?

Hymanson: I just never know when to trust my eyes. I always wonder, “Oh, am I simply too attached to the flat colors that I’ve been staring at for a number of years now? Why?” Maybe that’s a product of spending such a long time on a film, you just grow so accustomed to how the uncolored footage looks. Color grading is very much a process!

Filmmaker: The film premiered at the True/False Film Festival in 2020, a few days before things were initially locked down due to the first wave of the pandemic. What was the experience like of finally sharing the film with an audience, having been so attached to the material and to Jackie and Don for so long?

Hymanson: The festival was a lot of fun and I still feel very lucky and fortunate I was able to have that in-person screening. There are so many people I know who also finished films around that time but never got to have an in-person premiere. Jackie was able to attend the festival with some of her family, which was great, and Isidore and our producers were in attendance as well. It was sort of a dream-like experience, to watch the film in a packed theater with Jackie there. It was definitely meaningful to me and I think Jackie enjoyed seeing the film in a theater.

Filmmaker: I wanted to ask about the current status of Don and Jackie’s house. You yourself recently lived in their home for a little while. What led to that temporary move?

Hymanson: I had been living in Paris for about two years. Then, right before the pandemic hit, we were in New York finishing up post on the film. During that time I was mostly just staying with friends as we were completing the color grading and sound mix. Once the pandemic hit, I didn’t have a permanent spot in New York to crash at. So, Jackie, having moved into a senior-living apartment complex [after Don’s passing], offered to let me stay in her house (which had been left unoccupied) while she and her family prepared for it to be sold.

I expected to quarantine there for a few weeks. I ended up being there quite a bit longer. Nonetheless, it was an incredible place to quarantine at, and I was happy helping get it ready to be sold. As of one month ago, the house finally has new owners who I’ve been in contact with a little bit. They seem to really care about the space and the history of the house. It’s sad that it’s no longer what it was, but I’m happy that the new owners seem to be great people.

Filmmaker: There was talk of your next project being about a group of folks who meet up every day in a New York dog park. Is that what you’re working on next?

Hymanson: Funny enough, I’ve primarily spent the last year-and-a-half working on a film about my experience at Jackie and Don’s house, working with Jackie to say goodbye to it, I guess. It’s more taking the form of a first-person documentary though. That’s what I’m working on now, like a sequel of sorts to So Late So Soon. Then I’ll move on [laughs].