Back to selection

Back to selection

Girlblogging: Cléo from 5 to 7

This post is part of a series, Girlblogging. Read the introduction here.

In the music video for The Verve’s “Bitter Sweet Symphony,” (1997), lead singer Richard Ashcroft walks down a blue-gray London street, bumping into passersby, bowling over the girls and pissing off the guys. When you’re famous and beautiful on film, these are things you can get away with. Ashcroft represents a thoroughly contemporary creature—the 20th-century star, who, on a small screen today, looks more or less like the 21st; the detached, ambivalent, self-involved face of the modern urban world; the flâneur with somewhere to go, or something to avoid.

Eventually, his bandmates join him. No man is an island. This is not so true for the Young-Girl.

Modernity’s dominant pathology is its desire to entertain. Everything is really about looking. We objectify ourselves in the vain pursuit of money, notoriety, image—in return, we are rewarded with a pretty succession of different objects upon which to set our covetous eyes. This looking-practice is malignant, and has metastasized.

Because she is so acutely conscious of being watched, the Young-Girl polishes her surfaces to a cold, blinding mirror-finish. As she becomes, through the camera’s aperture, a focal object—willing or unwilling, the recipient of the looking-relation—her gaze is concentrated as through a prism or a magnifying lens, beamed back onto herself. Her personhood becomes increasingly illegible. Unlike older, more human ideas of beauty (longer-form, less atomized, permitted to expand, to take up space) hers is immediate, flawless, alienated. We are much prettier now, and much more lonely.

Like Ashcroft, Cléo (Corinne Marchand) is a star: a famous singer. Cléo—short for Cleopatra—is a stage name, a singular image. Her given name is Florence, but she is almost always being Cléo.

Also, she thinks she has cancer. Her affliction, in reality, is girlitis: the associated condition of girlhood, the self-wounding self-involvement, the invisible illness. Though at times she glories in it, the girlblogger’s image drives her to tears, to starvation, to isolation, to callousness and cruelty. Girl loneliness is self-generated, but not so neatly self-imposed.

Cléo has a handler (who accompanies her on errands) and a lover (who visits her on occasion, when he’s not busy with more important things), but—for all intents and purposes—she lives alone. Like a cursed princess in a fairytale, she experiences life at a distance, locked away in a tower: her narcissism constitutes a high-walled fortress of self, which divorces her from public sociality

She is obsessed with mirrors, and with windows, which—in Cléo’s world—tend to stay closed. In this way, they become the same thing.

It is quite tragic. A window is designed to let you see out, and beyond yourself. Alone, it’s easy to die inside.

Projected onto the streets of Paris, in mirrors and mirrored windows and the eyes of other people, Cléo’s image takes on form and structure: a hostile, hermetic architecture. It may look like a nice place to live, but it’s not really hers. And besides, she can’t leave.

Everywhere she is pursued by her reflection; from flat, shiny external surfaces, it confronts her. Threatened by the inevitability of its own decay, the image that used to comfort her fences her in.

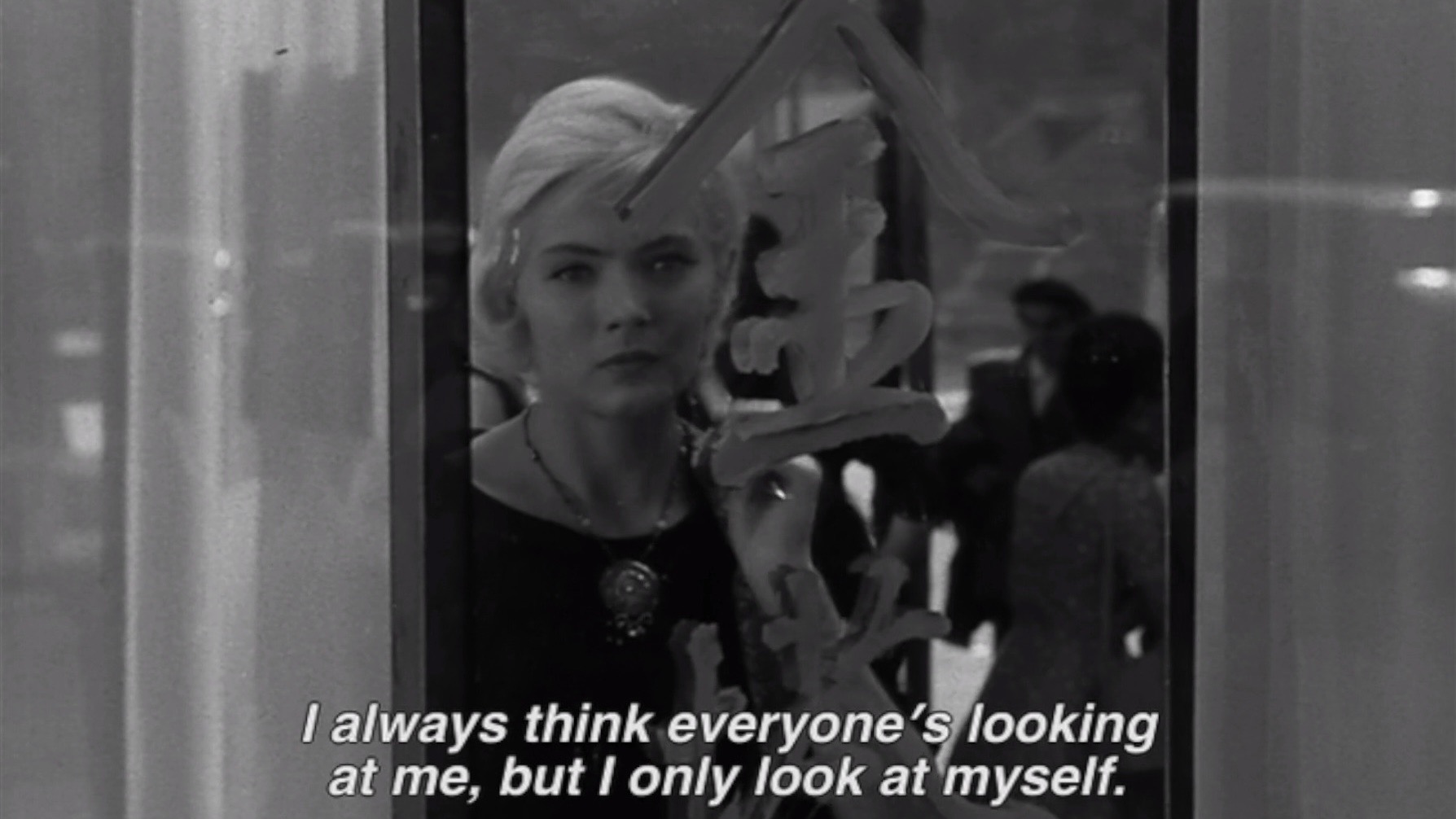

The act of looking places her between (behind) bars—she’s right about herself, after all, she is like a butterfly, preserved and pinned to a mat, kept for observation under a pane of glass. She is trapped in a particularly recursive looking-relation. She’s famous, instantly recognizable, and, on top of that, beautiful; she is leered at, or admired; she assumes everyone must be looking at her, all the time, because most people are. Though even if they weren’t, the effect would be the same.

The effect, of course, is that she is only ever looking at herself.

The effect is obvious, explicitly laid out in Cléo’s own voice, not like the writing on the wall—here, a mirror in a Chinese restaurant. The characters plastered over her face resist captioning (in French or in English); they seem designed to remain illegible, detached from narrative and narration, beautiful and separate.

She is a flâneuse; hyper-consciously solipsistic; in Ashcroft’s vein, a solitary wanderer, a famous face in the crowd. She depends not on people, but on their sustaining, tyrannical gaze. Cléo’s newest song is called “Sans Toi,” which means “Without You.” She can’t release it, she says; it’s far too lonely, too close to home.

Eventually, a young man stretches out his hand: a soldier on leave from the Algerian War which—in the bourgeois urban bustle of buying and selling, desiring and looking—is almost entirely invisible. At the end of the film, she’s getting a new lease on life. He’s probably going to die.

“I need to hear some sounds that recognize the pain in me.” Throw open the window—I’m nothing without you.

Read other posts in this series: