Back to selection

Back to selection

“Sit Here. Stand Here. Work Here. Slap Her Here”: Lav Diaz and Hazel Orencio on Phantosmia

Phantosmia

Phantosmia Since the late 1990s, Lav Diaz’s cinema has explored the Philippines’ troubled history with colonization, authoritarianism, corruption, poverty, macho-feudalism and the tensions that animate and enliven the sociopaths of today. His durational works are simultaneously a test of patience and spirit and assertions that the stories of Filipinos deserve time and space to unfold in all of its complexities.

Diaz’s works paint portraits of good men and women whose morals disintegrate along with their minds, poisoned by the pressures of the world, leading them to commit uncharacteristic acts of violence one would think they are too progressive or too intelligent for. As a whole, his work is a rich tapestry of the archipelago’s messy history with outside forces, and with its own people. The Diaz of today has pointed his camera towards terrorism within the archipelago inflicted by Filipinos onto other Filipinos, peeking into the psyche of those responsible for the country’s continuing sociocultural and historico-political fractures. His last three films—Servando Magdamag (2022), Kapag Wala Nang Mga Alon (2022) and Essential Truths of the Lake (2023)—examine the lives of men who transform into shells of their former selves after serving as high-ranking cogs in the machine of state-sponsored violence. Bodily malaise terrorizes his protagonists, almost as a karmic revenge inflicted by the unlived lives of the innocents. Their disabilities are impossible to ignore, forcing these men, and those around them, to reckon with their deepening guilt and unresolved grief from years of lending their bodies to the fascist state.

Rendered in black-and-white, Phantosmia (2024), his eighth film at the Venice International Film Festival, continues Diaz’s exploration of this griefscape and the moral decay of the contemporary Philippines. Master Sergeant Hilarion Zabala (Ronnie Lazaro), a multi-awarded sniper, has grown disturbed due to a recurring and worsening olfactory hallucination seemingly stemming from his time as a scout ranger and police officer. With his children growing distant, his house closer to collapse and the betrayal of his own body, Hilarion’s search for respite from his own psychosomatic ailment forces him to retrace his steps and finally confront the demons he has been trying to ignore, leading him to revisit his history of displacing and killing informal settlers and opponents red-tagged by the state.

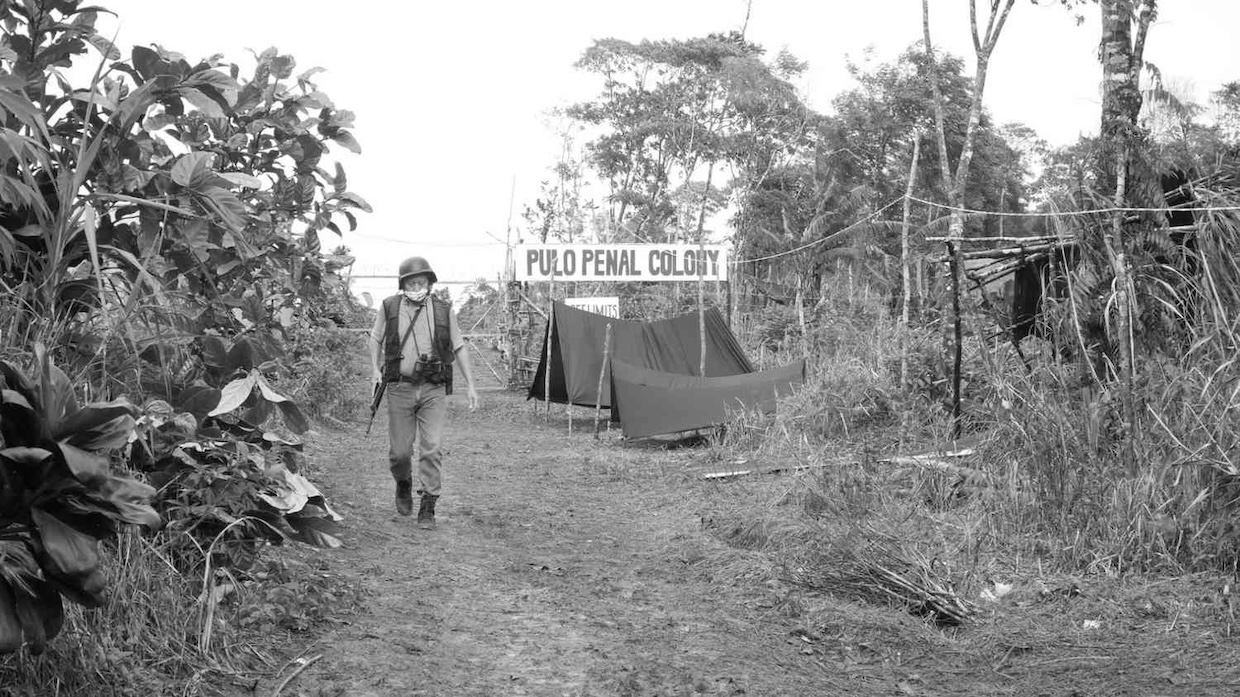

When this causes him to return to service at the Pulong Penal Colony, he encounters Reyna (Janine Gutierrez), a child trapped in a woman’s body, who is subjected to sexual slavery at the hands of her adoptive mother, Narda (Hazel Orencio), and her silently complicit brother Setong (Arjhay Babon). Hilarion’s resistance to being an instrument of murder is tested by his entanglement with this family and with the insidious and hot-tempered gunslinging Major Lukas (Paul Jake Paule), whose ironclad grip on the island is felt through daily reminders via speakers. Is it truly possible to escape, maybe even unlearn, one’s fascist, feudalistic,and barbaric tendencies if they are so deeply intertwined with one’s personhood and ways of being in the world?

A week ahead of the film’s premiere in Venice, Diaz and Hazel Orencio spoke to Filmmaker via Zoom to discuss the place of disability and familial disintegration in Diaz’s work, the moral crises that the work continues to orbit, the process of using cinema as a way to preserve cultural memory and nature and whether it’s possible to unlearn fascism in a fascist environment.

This interview was translated into English by the writer and has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Filmmaker: I’ve heard of anosmia before, but I’ve only come across phantosmia through this film. Even after talking to psychiatrists, it’s supposedly a rare disorder that has become more common as a side effect of long COVID. When did you first encounter the illness?

Lav Diaz: Years and years ago, I had a relative who was hospitalized at the AFP Medical Center in V. Luna. We were near his section. There were no names, but I could hear screams in one of the wards. It was a period where there was still a lot of conflict in Mindanao and the NPA [New People’s Army] had their peak encounters with the military. The patients suffered from what is colloquially called “war shock.” When I spoke to the doctors and counselors, they attributed it to trauma and PTSD. They mentioned phantosmia—problems with smells they couldn’t get rid of, which would cause them to go crazy. It could be the smell of death, rotting corpses, things they would smell during these encounters. It becomes a trauma.

Filmmaker: Was the illness the seed for the project or was it something else?

Diaz: It began as a simple story about a young policeman who witnessed the corrosive effect of corruption in the system and fought hard to not be affected by it. In the end, he compromises. But during the shoot, changes in production happened. In the original group, I was with two writers and the original story was from a friend of theirs—a true story from a young policeman. But when those changes happened, I changed everything and adjusted.

Filmmaker: When we spoke in May of last year about the tenth anniversary of Norte, the End of History (2013), you were preparing for a shoot in Quezon province. Was it for this film?

Hazel Orencio: Yes, it was last year! December 19.

Filmmaker: Til when?

Orencio: Til mid-February [of this year].

Diaz: It was very difficult because it was raining hard here. It was cold and windy. We shot only around two or three scenes a day because we were worried people would get sick.

Filmmaker: Are you in Sampaloc now?

Orencio: Yes! It’s like this place is our studio. [laughs]

Filmmaker: What is it about the location that made it fascinating as a setting?

Diaz: The place is an old, old town that doesn’t really change. The people are so nice and so good. It just so happens that everything we need is here. We shot the first film here with [the theater company] Tanghalang [Pilipino]—it’s set in World War II. So, we just created a village in the 1930s-1940s. The forests and the people call back to an “ancientness,” even their characteristics, behaviors, and values.

Orencio: “Old Filipino values.”

Diaz: The second film, Phantosmia, was [set in] a penal colony, so it was easy to set up. This new film [is set in] 16th century Philippines. It’s all here: rivers, forests, etc.

Filmmaker: Phantosmia finds you as the director, writer, editor, cinematographer and production designer again. You’re essentially immersed in the world until you release the film, maybe even after. What about this process of wearing so many hats is liberating and shackling?

Orencio: It isn’t Lav’s first time taking on a lot of the creative roles. He did it with Babaeng Humayo (2016) and with Ang Hupa (2019) onwards. Even many of his older works like Ebolusyon ng Pamilyang Pilipino (2005) and Siglo ng Pagluluwal (2011).

Diaz: We simplify the works. The main difference now is that I can have people work with me for design and for camera. For camera, I have around two to three people. For design, I have five. For admin, I have Hazel, my assistant director and my production manager. There are people who support us and we can pay people well. It’s still the same process, but we’ve expanded it. I don’t change the process. We never rent cameras. We buy cheap cameras and use them well.

Filmmaker: When you’re directing as the writer, cinematographer and editor, is there a conscious act of trimming that occurs as you’re on set? Or do you compartmentalize these decisions to the editing stage?

Diaz: I shoot with the edit in mind. I’m conscious of the trajectories of the narratives as I’m writing and filming it. I take care to know—even loosely—the order of the events, even as I trim throughout the shooting and editing. But the story is still the master. I still believe in good storytelling, in good design. Nature is always there as a force in my stories. It’s a fixation now, to have nature always in my works.

Filmmaker: One of the first scenes reminded me of Peque Gallaga’s Oro, Plata, Mata (1982). The image of burning huts recalls the desecration of the land that warns of the violence to come. What was the process of staging these larger scenes with fire and explosives versus the more intimate scenes filled with mundane but tension-filled conversation?

Diaz: It wasn’t hard because we had time. We weren’t rushing. We had time to prepare, casting people, finding the right places and locations, reconstructing the Maguindanao area before, the space of Sampaloc and people who really work within our process.

Filmmaker: Maybe it’s because I recently watched Marilou Diaz-Abaya’s Karnal (1983), but many of these scenes in Phantosmia reminded me of the paintings of National Artist Fernando Amorsolo. Farmers in rice paddies; rural utopia, which you later shatter. I know you also draw from literature and art while you create. Were you inspired by any paintings or was it informed by the location itself?

Diaz: Location and art, of course. You talk about Amorsolo. But the feel of Amorsolo is still here—the old traditions, the rice fields, how they work here is still the old way. Even their food and the way they eat it, habhab, it’s still here. Even the simplicity of the people.

Orencio: It’s still normal here for people to ride horses to go to work. It’s not a tourist area. There are no motels or apartelles. It’s a small town.

Diaz: It’s a fifth-class municipality.

Orencio: With only around 15,000 people in its population. They all know each other here. If you walk around, they’ll know you’re not from here.

Filmmaker: How did you come across this area of Quezon?

Orencio: Our art director, Allen Alzola, is from here. During college, I visited this place back and forth, so I became familiar with this place too.

Diaz: But it was by accident that we ended up here. The shoot with Tanghalang Pilipino was supposed to be in Cavite, but something happened and we had to rush to find a location. Tanghalang Pilipino had a schedule to adhere to, so we asked our art director if we could go to his hometown. When we got here, wow. Everything was here. It’s such a rich place.

Filmmaker: How did the collaboration with Tanghalang Pilipino come about? I know Hazel’s roots are in theater but I also know that you, Lav, have worked consistently with theater actors in your roster, some of whom have roots in Tanghalang.

Orencio: I was involved with Tanghalang Pilipino for a while. I auditioned for Actors’ Company in 2006-2007. During that time, it was under Dennis Marasigan. In my batch, among the auditionees, they would only choose twenty. Those twenty would undergo a workshop and they would pick only five. We went through a one-month workshop and I wasn’t chosen by the end. But I was able to work with them for two to three productions before I went to the Gantimpala Theater Foundation. But until now, I do know those in Tanghalang Pilipino.

Phantosmia is our second film with them. Our first film with them, which we were talking about, is called Kawalan [has yet to be released and is currently in post-production]. That film has almost all of them and was also produced by them. It just so happens that Phantosmia was released ahead of that. With that project, we were able to see the acting ranges individually. We were already familiar with them. But when we were casting Phantosmia, Lav had the idea of giving certain roles. That’s where it all started.

Diaz: It started pre-COVID. Tata Nanding Josef approached us and asked: “Would you like to collaborate with us?” They had extensions of what they wanted to do. They wanted to try cinema too, so they asked us about a budget wherein we could work. We gave a project but then COVID caused delays and delays.

Filmmaker: I ask because Toni Go [who plays Hilarion’s daughter Aling] and Lhorvie Nuevo [who plays psychiatrist Dr. Corazon Valle] were also in a restaging of the Filipino adaptation of The Crucible (Ang Pag-Uusig) by Tanghalang Pilipino, which we happened to see each other at. They’re considered two of the best theater actors in the country. Did their performances there put them under the radar or were they on your mind before seeing their theater work?

Diaz: Yeah, we observe a lot during plays. I took notice of Toni, of Lhorvie, of Marco [Viaña], of Tad [Tadioan]. I mark who would be good for particular characters I am writing.

Filmmaker: The most striking scenes in Phantosmia are ones where the frame is submerged in darkness and when the camera focuses on a very small space. You pay attention to the minute decisions and changes in the expression of the actors. What cameras did you use? What was your setup?

Diaz: It’s simple. For the night scenes, I use the tiny Sony A7S3. For the day scenes, I use the Fuji XH-2. Very small but great cameras. Our night scenes only used one light. You don’t need to use a lot of light. If you only have a small candle or lightbulb, it’s okay.

Filmmaker: Considering it’s in the dark and with minimal light amidst all of these natural forces, how did you work with the actors? I know that from even before Kapag Wala Nang Mga Alon (2022), all you really tell your actors is where the frame ends and begins. But what about when they’re in these conditions?

Diaz: There are rehearsals and readings with Hazel and the group. We’re ready. They know the process. We don’t use a lot of lights and don’t have a lot of people. To me, it’s very distracting. It needs to be intimate. I love that kind of work, where the collaborations and dynamics are rooted in just being there. You’re not distracted by 150 people moving around and all over the place. We’re just 10 to 12 people. It’s good. We can really focus on what has to be done. For the actors, it’s important for me that there are no distractions. I just give instructions.

Filmmakers: What kind of instructions?

Diaz: Usually movement. If I ask for something, [it’s] like if they can cry in a particular scene. If they can’t, it’s okay. Just as long as you feel it. It’s simple dialogue or communication. The image is very strong even without those grand displays of emotions. I just want people to be honest, truthful. You don’t have to fake it. Or act. You just have to feel it.

Filmmaker: Many of these actors you’ve worked with already.

Diaz: You don’t even need to talk about it much. Just give them the script and let’s get it on. [Laughs] Of course. And instruction: “Sit here. Stand here. Work here. Slap her here.” [Laughs]

Orencio: Especially with Ronnie Lazaro. He was the one who worked with Lav the longest in the Phantosmia cast.

Diaz: At this point, he just raises a dirty finger at me. [Laughs]

Orencio: He doesn’t give many instructions to Ronnie. They just look at each other and they know. [Laughs]

Filmmaker: You’ve worked with Ronnie for more than a decade now. I mean, it began with Naked Under the Moon (1999) and in Heremias (2006), he played the titular role. But for much of this film, his face is partially covered by a handkerchief due to his character’s phantosmia. His eyes convey the character’s world-weariness, but I also understand that the face is so important for an actor. What was his reaction to that creative decision? Did you have to negotiate that?

Diaz: We compromised. Of course, he wants his face to be seen. There were expressions he wanted to convey. He questioned why it needed to be fully covered. If he removes it, at some point, we might forget that he has an olfactory problem. The audience will pick up on that. So, we devised a way for him to remove it and put it back on. He and the audience can’t lose the awareness of his phantosmia. It has to be a persistent problem.

Filmmaker: Hazel, your character is quite different from the roles you’ve played in your previous films. Here, Narda is a cruel adoptive mother who sells her adoptive daughter, Reyna’s, body and controls the goods in the Pulo. What went into the process of crafting the character? And how did you split your time as both a production manager and supervising producer and also as an actor for the film?

Orencio: It’s normal for productions to have problems. The behind-the-scenes is sometimes more colorful than the actual film. It was a rough ride. There was a chance that we weren’t moving into production. Producers backed out. Actors backed out. It was the Christmas season. At some point, I was so anxious. We were on location. We had already set things up. The crew was ready. The shoot was in two days and people were backing out. How do I tell my people that the project is kaput? It’s almost Christmas and everyone’s banking on the project so we’re able to give something to our families. But how do you move forward without producers and actors? We coudn’t tell our team because they were already celebrating.

At some point, I became depressed and cried alone in a corner. I couldn’t show Lav because I had to be tough. I’m sure he had his own demons too that he didn’t show me. We had to be strong because we were the heads of the production. But I was the mother of the production. I was expected to provide and I couldn’t. Where were we going to go? Suddenly, help came and everything just flowed until it ended. Maybe that’s how life is: somehow you overcome seemingly unpassable obstacles. It only dawns on me now that maybe that was my motivation for being such a cruel mother figure. I poured out all of the frustrations, all of the anxieties and the depression into that role because that was how I felt at the time. Going through that mental and emotional turmoil prior to a shoot separated this project from all the other projects we’ve done together.

Of course, we submitted to different festivals, including Cannes, but we got rejected. People think that because it’s a Lav Diaz film, we always have a spot at the top festivals. But no! We get rejected regularly. It’s part of it. Now in a few days, we’re premiering in Venice. The rejections are starting to make sense. The lineup of the out-of-competition section is so overwhelming. The journey feels right. I feel like when I arrive in Venice, I’ll be crying. [Laughs]

Filmmaker: This is the first Lav Diaz film with Janine Gutierrez, who is considered one of the country’s best young actors and who comes from a family of Filipino film stars. She’s starred in several independent films like Babae at Baril (2019) and Bakit ‘Di Mo Sabihin? (2022). How did she get onboard?

Orencio: Janine and I worked together on [the television show] Dirty Linen. I was one of her best friends [on the show]. It was on that set that she expressed to me that she wanted to work with me and Lav. The first was also Kawalan and then the second was this. By this time, she already knew our process. It didn’t take much to adapt to us, and considering we shot this during the holiday season, she was so game to give us time to shoot in Quezon. Sometimes, in our scenes, she’d [be so committed that she’d] tell me to actually hit her. Of course, I wouldn’t do that—we have devices and cheats. But we had to make it appear realistic. Janine really trusted me and we both trusted Lav that we’d both be safe, even if the scene made it seem like we were violent.

Diaz: Janine is brave. It’s her first time with us. There are only a handful in our team and we go to dark places. She’d walk in the mud. We’d warn her and she’d tell us: “No, no, no. It’s okay.” She lived the process. It was a slow burn. Nothing was rushed. We prepared well. Even if we filmed only two to four scenes a day, she wouldn’t complain. In TV, you’re used to doing sixty scenes a day. [Laughs] She entered a different milieu and a different dynamic of creation, far away from what she’s used to. You’re in a far-flung area and anytime, somebody might even recognize her because she’s a big celebrity. But she wasn’t afraid of that.

Orencio: I wasn’t sure if she’d be able to adapt knowing that we first met in Dirty Linen, where she was the star. There, we had tents, air conditioning, and she even had her own assistant and driver.

Diaz: She came from a very sheltered setup.

Orencio: I had to inform her that we had a different setup. It’s not comfortable. But this was one of her dreams. In the end, she was delighted by the process because for the first time, she also didn’t need to wear makeup during the shoot. That’s how it is with us. She felt so free. She told me that with us, she could finally sleep properly. I’m happy that she blended well with us and with our process of making. She wasn’t a diva at all.

Filmmaker: After Phantosmia, I noticed two recurring themes in your works—the first is how disability in your films is used to indicate a deep psychological fracture and the second is how these are tied to, if not the cause or effect of, familial disintegration and parental failure. Here, they’re embodied by Hilarion and Reyna—whose disabilities remind them of the violence they enacted or received, respectively. What attracts you to these themes?

Diaz: I was witness to these conditions, life’s dysfunctions, coming from a place like Maguindanao. You just look around you and there’s fractures. There’s too much poverty in the places where I grew up. We kept drifting across Datu Paglas. There’s too much violence and displacement. It was a natural attribute of life. I wanted to work on that because I see life in that way, coming from this realist and underbelly conditions. We’re people who can work around it. Eventually, we can fix it. We see the good and the bad, the little things, the verisimilitudes and vicissitudes of life. I want to work on the small things to create this big humanist perspective. I like that kind of storytelling because I experienced these.

Filmmaker: In Phantosmia, there are repeated instances where characters eat but Hilarion rejects breaking bread with them. On the other hand, Narda constantly communes with others but uses these to conceal her reprehensible motivations and actions. Sharing food is such a huge part of building community, especially in the provincial Philippines. What made you write in this behavior?

Diaz: The military perspective is of isolation. The rangers are a special unit in the military that hinges on independence. They train in the forests and mountains to be able to survive on their own. When Ronnie and I were talking, we wanted to combine the isolation and desolation and wanted it ultimately to look like he was an outcast, like he abhorred socializing because of his background. Part of it is also his attempt at concealing his phantosmia and his disgust, because he’ll have to react to food. But it’s really the ranger culture. It’s his culture, it’s isolation. Even from the military institutions, they can move alone and work alone. They can survive. That’s how they’re trained. He wants to do it on his own terms.

Filmmaker: Phantosmia has no cure, only treatment to assuage the symptoms. But here, the psychiatrist Dr. Valle makes it explicit: he has to confront his past. He moves back to the colonies and writes a journal. In an extended sequence midway through, Hilarion’s writing enables the film to weave in and out of the past, allowing us to experience the aftershocks, distorting time. Why this device?

Diaz: They do that in counseling. I just adapted it. But it was poetic, in a way, to use literature, writing and voice-over. In cinema, writing and using words that come from within is a really powerful medium, but the diary-type of counseling is actually done. They make military men write about their first day in service until the present. It’s part of the healing process, but I adapted it to become more poetic.

Filmmaker: You have a character Marlo (Dong Abay) who swoops in, wearing an all-white ensemble, and begins reciting poetry amidst these different crises. He, at times, reminds me of the filmmaker and performance artist Roxlee, who is one of your dear friends. It’s a peculiar sight in this milieu. Why insert this poet in the Pulo? What does he challenge?

Diaz: The role of the poet—whether spoken word or written—is to raise the conversation to a different level. It contextualizes the whole perspective of the film. Poetry’s effect is different. I wrote three poems for the character of Marlo. The first, he searches for what appears to be absent. He looks for Reyna and does not find her, then talks about what remains invisible. The second is his big scene where he stands on a raised makeshift platform. Unike everyone else who is there to hunt the Musang, he treats the Musang as his muse. It offers a different perspective, breaks away from the tradition unfolding in front of him. That is the role of poetry: to humanize, to be truthful, to tap at something more spiritual. Poetry asks us to transcend the visible, especially when the poet is thrust in the middle of all this chaos. In Hell, in the abyss, poetry changes the scene. All art—whether song, dance, painting, etc.—is capable of this.

Filmmaker: Where did the Haring Musang tradition come from? Is it a real tradition?

Diaz: No, but that’s how it was before in Maguindanao! There would be groups of hunters who’d arrive at our barrio and who’d hunt the wildcats or even the Philippine eagle. I grew up that way. I just expanded it. They used to sell the claws and preserve them. They were expensive. Hunting season was a tradition then in Mindanao.

Filmmaker: You start the film with Hilarion’s encounter with a community of Christians and Muslims headed by Babu Labi [Loreta Derecho] in Cotabato, who Hilarion is unable to protect despite his promises. As a sheltered person from Northern Luzon, I was admittedly unfamiliar with the conflict around the Ilagas in Mindanao, which you describe as a Christian militia, and the subsequent counterviolence. Could you talk more about that political period?

Diaz: The atrocities began in our area of Mindanao in the late 1960s. The conflict between Christians and Muslims had started then. The Muslims began the Blackshirt Movement and attacked Christian settlers and communities, while the Christians, with the support of Christian politicians and the military, created the Ilaga militia. They were brutal people. They started fighting back and it became this back and forth. It was very violent til the ’70s. Lots of bloodshed. In the 1970s, it became more politicized. But before that, it was just survival. The Ilagas were mostly Ilonggos and the name meant “rat.” They would raid and attack Muslim communities, burn the place, and massacre [people]. The Manero brothers, who murdered Fr. [Tullio] Favali, were Ilagas. These militias were spawns of that movement. They call it a movement, but it’s really not. They were created by the military and the corrupt politicians there. It was quite brutal and bloody.

Filmmaker: Phantosmia is bookended by scenes that use religious conflict as a justification for violence. Hilarion, at the beginning, believes he’s doing the right thing. But eventually, he realizes these killings were part of a larger apparatus of violence and that he needed to create justifications to absolve himself, at least temporarily. What was the process of writing about the politics that serve as the backbone of Phantosmia?

Diaz: Part of the mandate of police institutions and military institutions is killing. They were conditioned that way. To kill is a duty. Even Hilarion’s father was like that—militaristic. He was brought up that way. He was born into a life steeped in fascism. It’s why the process [of moral reckoning] was so slow before he realized that killing is wrong. It’s not a duty to kill, never a duty or a mandate. The conditioning of police institutions and military institutions is so wrong. But they develop an entitlement that calcifies into abuse that externalizes in different ways. They’re not conditioned well. Guilt isn’t an issue when they kill because they’re conditioned this way.

Filmmaker: As Phantosmia progresses, we come to realize that Hilarion is in need of a form of absolution and retribution, a figurative way to wash his hands of that fascism and guilt. But he seems to realize that to break the cycle, he still needs to participate in it at least one more time. It’s a scene that is both hopeful and bleak.

Diaz: Hilarion Zabala needed to be in a different milieu to achieve the absolution you’re talking about, but he does it by liberating people. In this case, it’s Reyna. He doesn’t consciously do it to redeem himself. It goes back to duty and sees that his duty is to liberate this woman from the oppression that she’s suffering. But the evil of the area isn’t just in the mother, but also the superintendent. So again, it’s never a duty to kill but I have to kill this [fascistic] man. That’s the contradiction, the irony. The absolution and redemption are organic. It springs forth from what’s happening in his environment and it’s beautiful that way. It’s not imposed redemption. He develops this awareness from observing. In the military, he can’t see this because his perspective is limited. Now, it’s changed. This more spiritual aspect of the film emerges from that.

Filmmaker: This religious radicalization connects Ronnie Lazaro’s characters in Phantosmia and Alon. But while Primo Macabantay is a radical evangelical figure who resorts to killing, Hilarion in Phantosmia wants penance and seeks to avoid murder at almost all costs. There are images here that recall the pasyon and other religious acculturations that allude to this desire for penance as well. Do you think absolution for such corrupt figures is possible?

Diaz: The Catholic perspective seems to adopt this idea that even if you’re the worst kind of criminal, you can be redeemed. You can still enter the kingdom of heaven if you show genuine remorse and penance. Christ will be waiting for you. There’s an irony there: that you can rape your ten children and kill your wife, but as long as you go to a priest, confess, and express remorse, the gates of heaven will be open for you. St. Peter might even be there with fried chicken at the doorstep waiting for you. [Laughs] Other religions also have this. It’s such a privileged teaching.

But it comes from a context—or a hope—that people can change. We must be dialectical about it. Where is he coming from? What led him down this path? It should be that way. Some people are judged to be criminals right away, but maybe it’s a chemical imbalance, psychosis, or the environment where he comes from. That’s the Christian perspective: forgiveness requires that we enter another’s vantage point. What’s your provenance? What’s your history?

Filmmaker: The conclusion of Phantosmia reminds me of Norte, with both characters on a boat towards an unknown destination. But while the ending of Norte invokes stasis and purgatory with how the boat is framed between the water and the sky, the end of Phantosmia depicts Reyna’s escape, one that opens her up to childlike joy as she leaves the frame. Why was it important for you to conclude with this?

Diaz: We know that many things will still happen to the character. The people of Pulo might come after her or maybe they’ll kill Ronnie. But for her, it is already freedom. I wanted to end with hope. It’s more of a feel. It’s a start.

Filmmaker: In his review of Essential Truths of the Lake (2023), film critic Daniel Gorman likened your prolificness to Hong Sang-soo. He’s made around 19 features in the last decade; you’ve released 15 features and counting. Your films and philosophies are undoubtedly different. But you’ve released at least one feature every two years since 1997. Many directors take lengthy breaks in between projects, especially because of the pandemic. Is this a rhythm that you’re comfortable with? Have you reflected on what keeps you going at such a prolific rate?

Diaz: There are gaps usually because many directors want to shoot with big budgets. They want to shoot every time, but it takes time to get those budgets. For us, for my ideas, I tell Hazel that we need to prepare for a shoot and just go. I imagine that we’re just telling stories on the street. That’s our culture in Maguindanao. You go to the streets; we talk, we tell stories. I want to work that way. I don’t want to be hampered by a lack of budget, a lack of support. We have cameras, friends who can act, who can come with us. So, let’s go. The money will come later. That’s my perspective. It’s what happens. Now, people are supporting us. That’s just my process. I don’t want to stop. Until there’s a story, until there’s a perspective to be pursued, I want to keep mining the human experience. The creative process, the reasons why I keep making films, is still a mystery to me. But I love doing it. The stories keep coming and of course, there’s a responsibility to tell these stories.

Filmmaker: What’s the responsibility exactly? Is it a moral imperative?

Diaz: Yes. This fixation of nature comes from the dread that nature is disappearing. I want to sculpt my cinema with nature. My motto is: “We will remember the world with cinema.” And it’s true. For example: We’re shooting in Zambales, on a formidable beach, and by the time we return after the shoot, the beach is gone. It’s been swallowed by the waters because of black sand mining. Part of it is this responsibility to sculpt nature in our memory. Cinema is also memory. We’re reclaiming things so they don’t disappear into oblivion. It’s a cultural act for me, even ideological, saving nature in my films. It’s too daunting to try and save the whole world. That’s too large. So, we try to save parts of it that we’re lucky enough to move through.

The nature here in Quezon is beautiful, but it is also slowly being erased because of logging. The places where we’re shooting? In two or three years, they might vanish. But they’re sculpted in our cinema. We’ll remember these places through cinema. At least part of it, I hope. It’s so easy to create and shoot in studios and do sets, but we’d rather find places that feel right. It helps from the perspective of people who work within cinema. At the same time, culturally, our people learn to work around these places and communities get to be involved in telling and shaping the story of our country and how our people live.

***

Lav Diaz’s Phantosmia had its world premiere on September 2 at the Out of Competition section of the 2024 Venice International Film Festival.