Back to selection

Back to selection

Proud Boys, Bears and BDSM: Camden International Film Festival 2024

Apocalypse in the Tropics

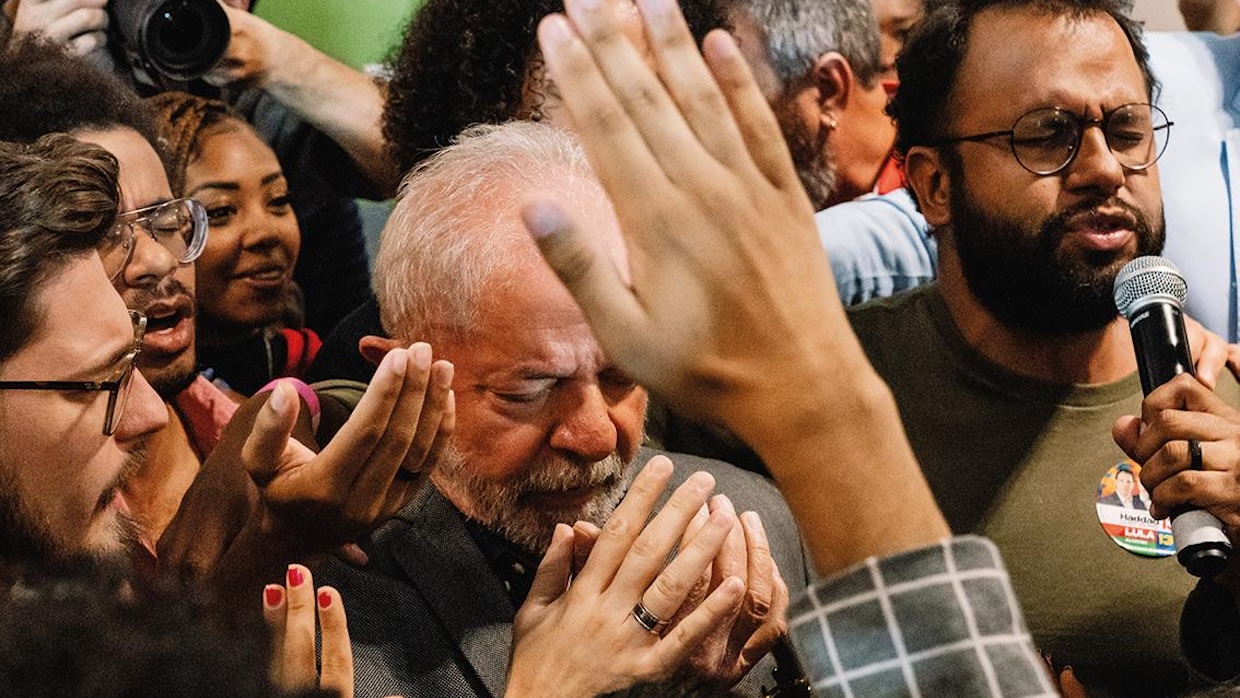

Apocalypse in the Tropics Given the jittery churn of U.S. election year media in a late-capitalist death spiral, it can help to look elsewhere for a parallel perspective on the rise of illiberal authoritarians and a mass public siege on the seat of national governance, a la the Jan. 6 insurrection, amid their downfall. If nothing else, what has happened in Brazil over the past several years offers a startling, even unreal reflection of post-MAGA America, with the presidency of right-wing blowhard and Trump wanna-be Jair Bolsonaro ascendent amid a corruption scandal that sent his competitor, leftist Workers Party candidate and former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, to jail.

Apocalypse in the Tropics, Brazilian filmmaker Petra Costa’s sequel to her Oscar-nominated 2019 The Edge of Democracy, captures the volatile, polarized mood as Lula is sprung free and makes his return to power, focusing specifically on the strategic role played by Brazil’s evangelical movement in boosting Bolsonaro along with other like-minded politicians and judges, and its incendiary role in the sacking of iconic Oscar Niemeyer-designed government buildings in Brasilia, the nation’s capital, on Jan. 8 last year. This made for a very timely opening night selection for the Camden International Film Festival, now celebrating its 20th year as a nonfiction powerhouse in coastal Maine. As with her previous film, the story is told by Costa in a calm, deliberate voice whose soothing quality contrasts paradoxically with much of what she describes. Especially during sequences where a drone camera floats smoothly overhead, her narration has an elegance that can dip into foreboding emphasis at the end of a statement. There’s plenty to be unnerved about, as Costa explores the pivotal role played by tele-evangelist Silas Malafaia, a fiery kingmaker who commands an audience of some 50 million Brazilian evangelicals—a demographic, Costa observes, that has exploded in contemporary Brazil, nurtured by extensive and calculated American influence that began in the 1960s to counter the rise of liberation theology. Costa’s close-up encounters with Malafaia show a puppet-master with no shame in exerting his considerable power, a force to which even Lula must to some degree capitulate.

Back to America’s populist fury: Homegrown follows three Proud Boys in the months leading up to Jan. 6, 2021, culminating in filmmaker Michael Premo’s headlong immersion in the event itself, holding a camera as one the film’s subjects—Chris Quagley, a radicalized 38-year-old New Jersey-ite—goes full-tilt into the fray. The footage resembles so much of what everyone has seen already, but the hair’s-breadth perspective following Quagley’s own has a fresh intensity as he gets repeatedly pepper-sprayed in the face and beaten while shouting himself hoarse amid the chaos. For all the aggro bluster that leads to this moment, Quagley appears to be mostly ineffective as an insurrectionist, and later that night gets run off the street by Washington D.C. police while grilling steaks for his crew. When he winds up sentenced to a dozen years in a maximum security prison, you surprisingly feel sympathy for him. That says a lot for the filmmaker’s even handed approach, and a knack for extended access with weekend warriors who have no reserve about loudly announcing prosecutable intentions for anyone to hear. The film consistently juggles banality with bloody-mindedness, as when Quagley segues from building a crib for the child he and his wife (who happens to be Chinese) are expecting to showing off his collection of semi-automatic weapons. But Premo searches beyond what could be cliched: Another subject, Thad Cisneros, offers the angle of Hispanics who are increasingly down with MAGA—and, in a bid of seeming incongruity, he seeks an alliance with a Black Lives Matter leader. Despite some important shared common ground, the parties fail to cohere, and Cisneros (who also eventually landed in jail) does some soul searching. The film’s pensive aftermath leaves the future uncertain, much as Costa leaves the audience with an uneasy ellipsis.

The festival itself, however, appears to have weathered a leadership transition with much less tension. Ben Fowlie, who founded CIFF and was executive and artistic director of its umbrella organization the Points North Institute, stepped down earlier this year. Elise McCave, formerly head of film at Kickstarter, is the new executive director of Points North (while also continuing in her ongoing role as moderator of the Points North Pitch session at the festival); Sean Flynn, formerly program director of Points North, is now its artistic director. “I’m carrying all the responsibilities I had before, but expanding to include curating the festival,” said Flynn, who has been with the festival since 2010. Reflecting on the organization’s expansive arc across two decades, he noted, “These seeds were planted and they continue to grow and take on a life of their own. It’s something that has grown out of this very fertile soil and been nurtured by so many people. It’s always kind of humbling to step back and see how far the branches reach.”

The festival, whose screenings and events are divided between the coastal towns and historic venues of Camden and Rockland, has grown over the years in its industry prominence, arriving as summer melts away into awards season. At times, the festival could feel a bit overloaded with higher profile, streamer-backed features versus more esoteric international discoveries and the ambitious projects cultivated through its own filmmaker support programs. The impact of the pandemic also cannot be underestimated. This year, though, CIFF really felt like it was “back,” in terms of tangible matters like full theaters and intangible things like—the buzzword of the day—vibe. The country may be polarized, but there’s no need for the festival to be. “I really wanted to come into this year trying to find some cohesion across all those different constituents and the experiences that they were having,” said Flynn, citing the multiple facets of industry, filmmakers and audiences the festival has to engage with each year. “So much of the secret sauce here is that combination of the local and the global. How do you have a festival that can meet people where they’re at and create shared experiences?”

Last year, the annual Points North Pitch was interrupted and forced to quickly relocate by Hurricane Lee. With sunny skies, the 2024 edition proceeded as normal, as six teams selected as Points North Fellows pitched their projects to a panel of funders and distributors (including representatives from POV, Impact Partners and Chicken & Egg Pictures) before a loudly enthusiastic audience at the Camden Opera House. The session included fellows with projects from Chile, Romania, and the United States,; from the latter, Riley Hooper—joined by Bryn Silverman, who produced her film along with (Sandbox Films’ newly appointed head of production and development) Caitlin Mae Burke—won the Pitch award for $10,000 in post-production services from Boston-based Modulus Studios. Hooper’s Vestibule lays out the filmmaker’s 10-year effort to deal with vestibulodynia, a condition of chronic pain at the entrance of the vagina, which becomes “a multi-generational story about sexual health, pleasure and agency.” Hooper was gratified such a personal project resonated so strongly with the Camden audience. “My producer Bryn Silverman and I had so many people come up to us and tell us stories about themselves, or people they know who have experienced similar issues, or just struggles around accessing healthcare or advocating for their own pleasure in general,” she said. “A lot of people told us the pitch made them cry. I think when you start to open up and share things that are normally kept silent, it’s an opportunity for people to start coming out of the woodwork and being able to say, ‘Me too.’” Between nerves, the intensity of the experience and her own vulnerability in the spotlight, the filmmaker began to tear up in the midst of the pitch. “I wanted to stand on that stage and talk about these issues that are so often shrouded in shame and silence,” she said. “I wanted to talk about pleasure! In that moment, overcoming the tears, I was really able to use a lot of the embodiment tools that making this film has taught me to continue on and do the pitch.”

Receiving special recognition was House No. 7, whose Syrian director Rama Abdi and producer Hazar Yazji, unable to secure visas, pitched remotely. The film tells the story of three women and their struggle to protect a safe house they created for themselves after escaping abusive homes. Hooper’s success should help with the finishing the film, which will employ highly stylized dance sequences staged in a variety of sets based on key sections of the narrative. “The dance scenes play a very practical role of filling in the backstory,” said Hooper, who also explored Authentic Movement dance therapy as part of her healing process. “But it also made a lot of sense to me to tell the story about my body through my body.”

The themes that animate Hooper’s winning project find kindred expression in The Flamingo. This world premiere, from director Adam Sekuler, explores the transformation of 63-year-old Mary Phillips, liberated into a profoundly fulfilling and affirming realm of experience when she joins the BDSM community after more than a decade of celibacy following her divorce. The premise could have been fodder for one of the self-consciously “saucy” reality productions that litter the marginalia of many streaming platforms, but in Phillips the filmmaker has found a dream collaborator: open, unapologetic, sincere, relatable and far enough along into her new life that she’s able to articulate its pleasures and complexities with inviting candor. As playful as it is touching, the film demystifies the subculture that Phillips has embraced while not shying away from the graphic (if somehow never untasteful) particulars of her various carnal, emotional and psychological practices—which also include therapeutic non-sexual physical contact. With its expansive spirit, The Flamingo argues that we can save the world one soulful hug (or properly attenuated flogging) at a time.

Freedom becomes a complicated question for Sanyi, the eight-year-old protagonist of Kix. The doc covers a 12-year span in three junctures, checking in on its fiercely untamable subject in childhood, early adolescence and at the edge of adulthood, evoking such cinematic templates as Francois Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel cycle, Richard Linklater’s Boyhood and Michael Apted’s long running Up series. Kix begins in a more incidental manner, however, when onetime film student Dávid Mikulán encounters Sanyi and his older brother while skateboarding wildly through the Budapest streets, gleefully making trouble. Mikulán appears to have been making a “man on the street” piece, but is meaningfully derailed by this crew of boisterous provocateurs. Sanyi’s magnetism would be enough to power a bracing short film, an idyllic snapshot shadowed by the boy’s dire, impoverished yet roughly affectionate homelife, but the filmmaker returns (now working with co-director Bálint Révész) a few years later to find a budding teenager eagerly adopting adult vices, his inherent rebellion now more codified. The allure of the streets becomes more vividly evident every minute the camera spends in the family’s decrepit apartment—Sanyi, perpetually accompanied by his much younger sister, appears to live in a sub-basement with a dirt floor. In one ironically amusing sequence, the family takes sledgehammers to the walls in an effort to “renovate” before a visit from child protective services. There’s a vigor at work behind all these images, as the filmmakers engage their charismatic subject on an eye-to-eye level, trying hard not to manufacture some kind of urban ethnographic tract or fetishize the exuberance of youth in marginalized circumstances. When Sanyi’s delinquent habits eventually, and tragically, threaten a future he has only begun to credibly imagine for himself, the pain is very real.

Closing night’s world premiere of The Shepherd and the Bear was another richly satisfying reminder of the power of longitudinal verite, a movie about rigor and landscape and a long-abiding way of life high up in the French Pyrenees, where UK filmmaker Max Keegan and a very small crew spent several years amid a closely knit community of shepherds wrought up in crisis. As the title infers, the issue is bears—specifically, the French government’s decision in the 1990s to begin airlifting brown bears from Slovenia to replace a population wiped out by hunters. For the shepherds, the problem is the danger posed to their flocks, all-too-easy pickings for ursine newcomers that are likewise a lethal threat to humans who stumble onto them (or vice versa).

Early enough, the film signals its deeper interest in the human personalities (the bears are scarcely seen) for whom the controversy becomes a lively source of dramatic conflict. In his focused habitation with the community, Keegan witnesses a powerful example of human beings irrevocably bound to land they live off of, and exhibits pretty convincingly that they are far more ecologically mindful than the bureaucrats in Paris they denounce. The story pivots seamlessly between three main figures: the elderly shepherd Yves, suffering health issues as he nears retirement and deeply enraged at the government and the bears; Cyril, a teenager obsessed with nature photography, who aims to become an ecologist so, among other things, he can help protect the bears; and Lisa, a young woman whose shepherding days are, like Yves, heading towards a transition. Working with a unique, custom-made camera rig, Keegan offers a fairly convincing answer to the proposition, “What if Frederick Wiseman … but a mountain goat?” The often arduous experience of sharing day-to-day existence with these indelible characters permeates the images, which come insistently alive in the high-altitude light. Yves is especially dynamic, a chain smoking, hard-drinking, scabrous walking legend who appears as if summoned out of another era. The film’s parting shot, framed from behind as Yves looks out a window, the wrinkles on his neck like tributaries, does him poetic justice.