Back to selection

Back to selection

“We Couldn’t Find that Exact Beige — It Was a Real Struggle”: Production Designer Louisa Schabas on Designing Matthew Rankin’s Universal Language

Universal Language

Universal Language Driving around Montreal on a gray November day with Universal Language writer-director Matthew Rankin, production designer Louisa Schabas noticed an elementary school with a row of stark, monolithic concrete walls facing the playground. The slabs were at an angle, allowing for a series of black metal doors to open into the yard. “This is perfect for the market,” she said. With some painted signs indicating a random assortment of mom-and-pop shops, including a bakery and an office supply store, Shabas would later transform the building facade into a ramshackle Winnipeg mini-mall, with the striking anomaly that all of the signage was in Farsi.

A quasi-autobiographical melange of Quebeçois realism, Winnipeg absurdism and the metafictional humanism of Iranian cinema, Universal Language posits that geographical boundaries aside, we all share the same world and essentially speak the same language. At the same time, the film adroitly balances two different pedigrees. As Rankin has often repeated, “My go-to joke in Q&As is that Iranian cinema emerges out of a thousand years of poetry and Canadian cinema emerges out of 50 years of discount furniture commercials.”

It was Schabas’s job to translate Rankin’s gently absurdist vision to screen, creating a world that feels both quotidian and anachronistic. Schabas first worked with Rankin as the art director on the brilliant seven-minute short Mynarski Death Plummet (2005), a hand-made avant-garde “micro-epic” about a doomed Winnipeg WWII aviator. The Montreal-based Schabas has art-directed music videos for Arcade Fire, Celine Dion, and Kid Koala and been production designer for an eclectic array of independent films, including Denis Côté’s Boris without Béatrice (2015), Karl Lemieux’s Maudite Poutine (2016) and Jeff Barnaby’s Blood Quantum (2019), which won Best Production Design at the Canadian Screen Awards. Her ingenious style was crucial to creating the decidedly offbeat but totally convincing world of Universal Language, an international success that was Canada’s official selection for Best International Feature. Universal Language is being released in the U.S. on Friday, February 14 by Oscilloscope.

Filmmaker: So how did Matthew Rankin explain the idea for Universal Language to you? The mix of Quebeçois and Winnipeg cinema and Iranian film?

Schabas: Well, being friends with Matthew, we had been talking about different things over the past years. We had worked on other projects as well. He gave me the script one day and asked if I was interested. I went up to the woods to a cabin and read it, and I wasn’t quite sure I understood. And then I reread it three or four times. And started to kind of see where he was going with this. One of the main things when I got back after having read it was to sit down with him and talk about it. But also to go outside. And so we went out and drove around the city for a couple of weeks together and just looked at buildings and looked at spaces.

Filmmaker: Were there references to other films that he might have had in mind to inspire the look of this?

Schabas: Abbas Kiarostami, obviously. And the Jafar Panahi film No Bears (2022). He really wanted me to watch that, which I loved. I didn’t watch too many other films. I had never been to Winnipeg. So there was that aspect that was also. And I had never been to Tehran either. So there were these two cities that I didn’t really know very much about that I had to research.

Filmmaker: How much of your work on the film had to with finding existing locations and maybe just tweaking them a little bit? To start with the school that opens the film. Was that, aside from the signage, how you found it?

Schabas: There’s the signage. And I also built a wall because the wall didn’t quite work with the design of the interior, so there was a bit of a set in there, but the intervention was very simple, very minimal. A lot of the exteriors were, as we say, “as is,” although we did cheat brick walls. I had these fake brick walls built which were really fun, and we would just have them in the truck and place them to camera to create corridors.

FIlmmaker: It seems like you were working within a very specific color palette.

Schabas: Yeah. For the exteriors we were working with existing colors. So these kinds of beige brick buildings are very common in Winnipeg. We shot exteriors in Montreal, and we couldn’t find that exact beige — it was a real struggle. Some of the walls were too yellow, and some were too gray. So we really had to research and find these places, these bare walls. Without any trees or plants or things interfering.

Filmmaker: And with the interiors, like when we go inside the classroom, were you shooting on sound stages?

Schabas: Initially, yeah. That was the plan with production, to use sound stages. But even though they give rebates when you’re an indie film, it’s still extremely expensive. So we would have had two days to prep and then two days to wrap each set and a limited time to shoot. And I didn’t like the idea of that, considering the budgets we were working with. So one day while we were driving around the city, we found this building we loved, owned by Hydro Quebec. It was one of their old buildings, empty. Basically a giant kind of office, warehouse space. And I walked in there and immediately I said we have to build the sets in here.

Filmmaker: So which sets were built in there?

Schabas: Pretty much all of them, starting with the classroom. We went from room to room; we shot one set while building another set. And then we would strike it and build another one. So we were constantly doing this. What was great is that we were all together. We were all working — building and painting — while they were shooting, and the conversation was very fluid in that way. The costume department also had a room there. So everyone was in the space in Montreal, which was perfect.

Filmmaker: Who was creating the paintings and drawings that we see in the film? Those are so wonderful.

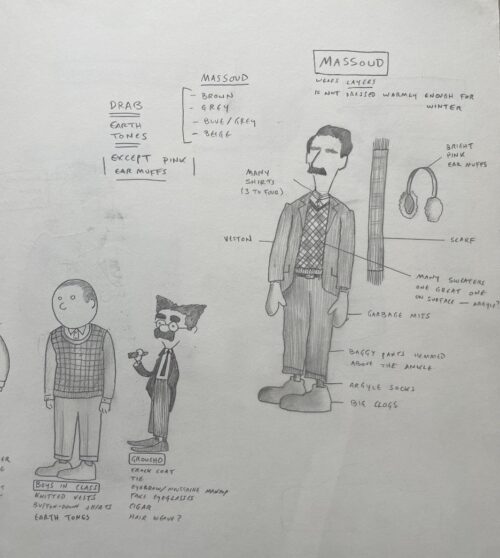

Schabas: I oversaw all the sets. And I drew the sets. And designed them. But I got artist friends, who collaborated for specific artwork. A lot of the graphics were done in collaboration with Pirouz Nemati, who is Persian and the main actor in the film. [He did] all the writing, the spell checking, the fonts. We did that together, which was really fun and hilarious. And then the turkey paintings were done by an old friend of mine who makes the most beautiful oil paintings.

Filmmaker: After the classroom, then you have the parking pavilion. And there’s just some very funny shots with the exterior of that building. Were you looking at buildings and collaborating with Matt about] compositions?

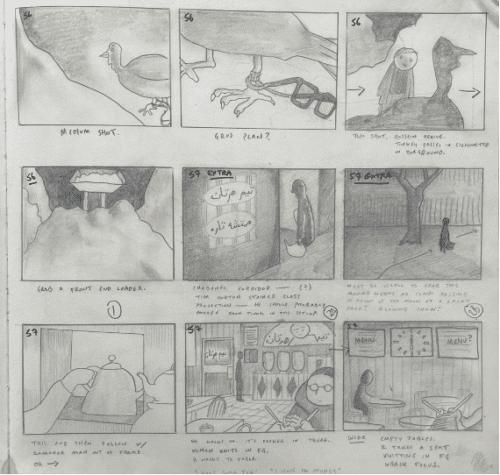

Schabas: Of course, yeah. He definitely had a storyboard–it’s almost a graphic novel that he had already drawn out. But then when we were finding these brick buildings and these brick walls, some of the composition changed. And we had to work with the snow as well.

FIlmmaker: I was thinking of the scene where you see Massoud (the sullen Winnipeg tour guide) through the arches. There’s real visual humor in many shots in the film, like a nod to Jacques Tati.

Schabas: Yeah, those were all great locations that we found from driving around during those weeks together.

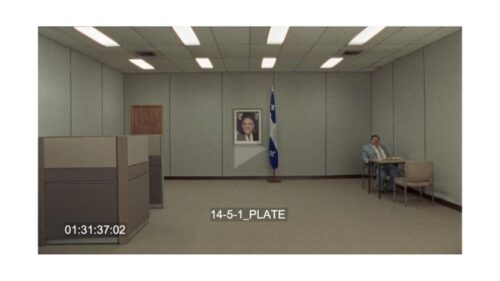

Filmmaker: The set in the Montreal office when Matt is quitting his mind-numbing bureaucratic job. The reverse shots show the exact same portrait on opposite walls.

Schabas: It’s very bare, but a lot of work went into it. Like all the walls were covered in this fabric. I wanted to make it very, very stark and clean. But the camera never moved in that; we just changed the door frame and the furniture. It’s a total fake.

Filmmaker: That makes sense. I knew there was some very simple trick like that.

Schabas: We did it slapstick there.

Filmmaker: You have several sort of offices or stores that are just hilarious, like the Kleenex dispensary. I’m assuming you designed the dots on the boxes.

Schabas: I actually got my son to stick all the dots on each Kleenex box. He was 13 at the time. It was a good job for him. But he did spend days, days working on that. That was a fun design. I drew that out, and then once we put the camera, we did move the Kleenex boxes around to make the composition and the frame more interesting. So that was one that kind of shifted the day of the shoot. But that was the nature of the film: things were planned out a certain way, and then we were still open to new ideas .

Filmmaker: I love the idea of the Tim Horton’s [donut shop] you designed, that’s reinvented as a very warm, sort of Persian place that serves tea along with the donuts.

Schabas: And has also maybe a bit of a 1970s or 1980s nostalgia, like how things used to look around here in Canada as well. It’s like taking different memories and things that exist but melting them all together, with a lot of jokes along the way.

Filmmaker: It’s a running joke that everything in the world starts to look the same, like the bus station where every poster from every country looks exactly the same.

Schabas: Yeah, I designed those posters. I was really scratching my head trying to translate what that bus station would look like. How do I make all these different signs? Because at this point you’re still in Montreal, you’re still in this kind of bureaucratic world, so it’s like two languages. The language before he gets on the bus is more of this kind of stark minimalist cold environment. And then once you travel, you get off that bus, then the spaces become warmer and more inviting.

Filmmaker: And then what about the shopping mall? The abandoned mall?

Schabas: Yeah. That’s an actual place in Winnipeg, right downtown. It’s quite depressing. There are still shops open, and it’s kind of a shelter, a place to stay warm, for homeless people at this point. They go in there when it’s minus 30, 40 outside. But they have all these like no loitering signs everywhere. So it’s this giant space that’s heated and just left for some shops and everything. But people aren’t allowed to go in there and stay warm and eat. It doesn’t make very much sense.

Filmmakers: Who created the murals that we see there?

Schabas: Sara [Shoghi], this artist illustrator. It was a collaboration with Matthew and myself where Matthew was saying what he wanted on those posters, and there was a lot of back and forth. It was really fun to do. And then we printed and hung them that day for that shop.

Filmmaker: We see an apartment building where these odd shapes that look like letters, red and gray, are almost painted on the side of the building.

Schabas: Oh, that’s also a beautiful apartment building in Winnipeg. Matthew’s from Winnipeg. [He was] born and raised and spent many years there and knows the city very well and has all of these favorite monuments. And I think writing the film and making the storyboards and everything, he had those specific places in mind. So, yeah, that’s a beautiful building.

Filmmaker: It feels like a movie that was very personal to Matthew. I mean, obviously, he’s in it and there are autobiographical elements in it. He lived in Iran, he had a bureaucratic job in Montreal, and his father was a Winnipeg tour guide. So it seems like he on one hand is making a very personal film but was also very open to a kind of collaboration and playfulness.

Schabas: I think one of the reasons why the film is connecting with so many people is that people can take their own stories from it. There is this kind of storyline that I connected with while making the film. My mother comes from Cyprus, and my father wasn’t born in Quebec. [But] I was born in Quebec, and all my friends are Quebeçois. I speak French. but I do always feel this, you know, “I’m here but I’m not here.” I come from here but I come from somewhere else. A lot of people like the Persian community we worked with are from Iran and [now live in] Montreal in the snowy winter and just like working with all these different cultural and geographical spaces that, you know, [summon] memories, spaces and things that belong to our own selves but then that we also share with everyone else.

Filmmaker: Roughly how long was the shoot? And were you there every day?

Schabas: I wasn’t on set every day. The art department was a small crew, so when they are shooting I’m busy working on another set. So there’s this dance that you have to do — I can’t be at eight places at the same time, unfortunately. But we shot in three different chapters. The first month, which was February, we shot in Montreal our exteriors. And then a smaller crew went to Winnipeg and shot there for two weeks, other exteriors, the Winnipeg exteriors, and then came back to Montreal and did all of the interior sets. So that actually was great for me in the process to be able to start seeing the film and what it’s going to look like and then tweak the interior designs according to the language that we have already shot.

Filmmaker: When I looked at the film again yesterday, just to sort of go through all the sets, like, it struck me how few there were, actually. it creates an entire world. But it’s done so sparely. It’s great. Have you been surprised at the response?

Schabas: Overwhelmed. It’s really nice to work and to make art and then to have–I mean, this is what I’ve been doing my whole life. So to get such a response from original work that you’re making, it feels great. I’ve worked on many films that got different kinds of reactions, obviously. But this is really a first. It feels wonderful. And it makes me want to make more art like this and to just keep going. And to keep working with Matthew, obviously.

Filmmaker: You’ve worked with a bunch of really interesting directors. So is there anything else you could say about his working method that’s different than others?

Schabas: I mean, he’s very loving and very cheerful, but also very specific and meticulous. Everything is thought out. I really appreciate that way of working. But then he’s also open to new ideas. And I brought new ideas to the sets, like the Christmas tree. He had always pictured it as being green. And I had always pictured it as being kind of pink and white and red. And so we kind of clashed a bit at that moment about the Christmas tree. I explained to him why. And he let it go. He said, “Okay, I’ll give you the tree.”