Back to selection

Back to selection

NEW YORK FILM FESTIVAL

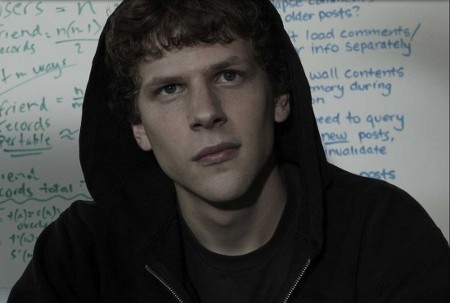

Like a bitch-slap to those who have accused it of excessive reverence for French fare over the past 48 years, the 2010 New York Film Festival is bookended and centered on American movies—oddly enough, all from the big studios. David Fincher‘s The Social Network (pictured above) opens the event September 24; Clint Eastwood’s Hereafter is the October 10 Closing Night selection; and Julie Taymor’s The Tempest, the Centerpiece.

I’ve seen none of them, but early reviews of The Social Network have been very positive, not surprising from the director of Se7en and Fight Club. Evaluations of Hereafter have been much less flattering, but then, it’s Clint Eastwood, and even a PSA would be worth a look. Critics have been hard on The Tempest, but what else would you expect with a film by Taymor? Hopefully it surpasses Titus and Frida. Perhaps Broadway suits her better than Alice Tully Hall.

The so-called Main Slate of 28 features (twelve more titles and discussions are part of a Special Events sidebar, though how the two sections are differentiated is beyond me) includes three more titles from the U.S. (Kelly Reichardt’s Meek’s Cutoff and two docs, Charles Ferguson’s Inside Job and Michael Epstein’s Lennon NYC), all non-studio. Add to that two films from the UK (Mike Leigh’s Another Year and Patrick Keiller’s Robinson in Ruins) and you get you a total of eight English-language pictures. From France, five. No one is guilty of francophilia; anglophilia, if anything.

Whether that’s a commentary on the quality and sources of contemporary film production or the mindset of the selection committee in touch with the zeitgeist is something I can’t answer. That half the choices are from the US, the UK, and France combined (and that such a high proportion were in Cannes, so in a way preselected by that festival’s programmers) might indicate limited outreach, but that’s to be decided after we’ve seen the films.

Although there are some fine movies in the selection, it appears that the NYFF has an identity problem in its home city. New Directors/New Films is comprised of (theoretically) edgy new talent; Tribeca, mostly conventional narratives with an on-the-way-to-Hollywood-or-Tribeca Productions feel. The NYFF does have seasoned masters (Jean-luc Godard, Leigh, Abbas Kiarostami, Lee Changdong, Manoel de Oliveira, Olivier Assayas, Apichatpong Weerasethakul) and some up-and-coming international fest favorites (Pablo Larrain, Michelangelo Frammartino, Cristi Puiu), but tossed in to the mix are some bizarre choices that feel like the selectors are attempting to be inclusive at the cost of merit. I’m trying to make sense of valued slots taken by such films as the not-quite-campy Mexican vampire flick We Are What We Are, by Jorge Michel Grau, probably the worst movie I’ve seen this year, and Austrian Benjamin Heisenberg’s The Robber, an uninspired, old-fashioned movie about a marathon runner-cum-thief.

The following are recommendations, films well worth the $20 cost of a ticket (a bargain, considering that the Big Three are priced at $40). Unless you can dip into a trust fund, you might want to go for the ones lacking American distribution. Of the titles I have not seen, the ones I’m most looking forward to, based on earlier work by the filmmakers, are three French pictures: Black Venus, by the Tunisian-born Abdellatif Kechiche (The Secret of the Grain, Games of Love and Chance); Of Gods and Men, directed by onetime enfant terrible Xavier Beauvois (Don’t Forget You’re Going To Die); and the nearly four-hour Mysteries of Lisbon, by Chilean expat Raul Ruiz (Three Crowns of the Sailor), who is, according to reliable sources, back in form after several misfires).

Silent Souls, Aleksei Fedorchenko, Russia

This is possibly the best, and certainly the most chilling, film in the festival. Its imagery calls to mind Tarkovski, Sokurov, and Paradjanov, but is a highly original evocation of the Russian soul. It haunts you and stays with you. The film is mostly an elegy to the wife of a factory photographer’s boss and to lost childhood, narrated from the beyond by the worker himself. The boss and employee, who harbors adulterous secrets from his chief, embark on a car journey to cremate the dead woman by a lake in another town.

The photographer tells us he is descended from the Merja, a Finnish-Ugric tribe with (according to him) set rituals and a strong attachment to water, which itself plays a part here. A sense of melancholy, of nostalgia for tradition, shadows the film. This is the first movie I’ve seen that shows bridesmaids tying threads to a bride’s pubic hair, then removing them and hanging them from a tree.

Le Quattro Volte, Michelangelo Frammartino, Italy

In rural Calabria, several non-events take their time unfolding. An old goatherd can’t keep up with his flock, then dies. A baby goat gets separated from the herd and takes refuge under a fir tree. The tree is cut down to be used in a village festival. All of this is framed by a charcoal-burning kiln. This is a poetic study of simple people whose spirituality is tied to their land. There is virtually no dialog, only cow and church bells and some snatches of Calabrian dialect. Poetic ethnography perhaps. In one fabulous scene, a dog whose job it is to keep the sheep together becomes a surrogate filmmaker, directing the action for several minutes. Le Quattro Volte is stirring in a quiet way.

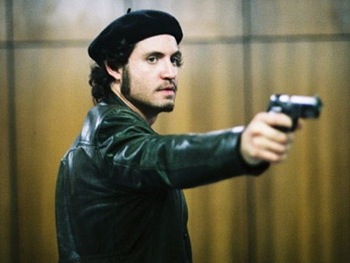

Carlos, Olivier Assayas, France

Venezuelan actor Edgar Ramirez gives an indelible performance as the astute chameleon Ilich Ramirez Sanchez, whose nom de guerre was Carlos but was labeled by the media as The Jackal. Now imprisoned in France, Carlos was the consummate terrorist-as-revolutionary. He worked with such groups as the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine and the Japanese Red Army. He hijacked OPEC delegates and took hostages. Extremely media savvy, he was constantly in the news and on the run. Handsome and charming, he was extremely authoritarian with his fellow revolutionaries as well as a womanizer. Originally a three-part tv series, this five-hour version moves rapidly. Like the energetic Carlos himself, it rarely slows down.

Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, Apitchatpong Weerasethakul, UK/Thailand

The film garnered Cannes’s Palm d’or from a jury led by Tim Burton, who told reporters that it took him to “another reality.” For Weerasethakul, the film is his reality, a reflection of his belief in reincarnation, coupled with a love for early Thai cinema. Humans in animal form have blazing red eyes, and the characters speak with little inflection, as they did in the Thai movies of his youth. Uncle Boonmee himself, played by a nonprofessional roofer, is a dying man who is visited by ghosts of his loved ones. Weerasethakul inserts a sequence with a bull, and one with an aging princess being serviced by a catfish, both of which may or may not be some of his earlier incarnations; the viewer decides. The film is beautiful to look at, with long takes honoring the jungle landscape and people of northeast Thailand. Uncle Boonmee makes the journey through the jungle to the cave where he thinks his first reincarnation took place.

The Autobiography of Nicolae Ceausescu, Andrei Ujica, Romania

Of all films to relegate to sidebar status. This is one of the strongest offerings in the entire festival. Ujica uses only archival footage in this potent documentary. He combines sequences of official Communist Party spectacles with home movies and footage of political meetings in order to track the rise and fall of his country’s dictator from 1965-1989. Some of the material is pristine black and white, some fuzzy video, but all is carefully orchestrated by the filmmaker to paint a portrait of the man, his opportunistic rise to power, and the devastation he wreaked on his country. An effective sound design heightens the impact.

Poetry, Lee Changdong, South Korea

In this gem, a grandmother diagnosed with early Alzheimer’s lives off a pension and part-time care of an elderly stroke victim. She has little time to gather the substantial sum required to pay her share of compensation to a mother whose daughter was gang-raped by her thankless grandson and his friends before she dove off the local bridge. (The ones who push the old woman to fulfill her quota are all younger men, fathers of the other boys.) She frets and scrubs but finds solace in a poetry class that she takes seriously, perhaps too seriously, until the resolution of her financial dilemma, rather than “divine inspiration,” provokes her to write the poem assigned by her teacher. Yun Jung-hee is memorable in the central role.

Revolucion, Fernando Eimbcke, Patricia Riggen, Gael Garcia Bernal, Amat Escalante, Carlos Reygadas, Mariana Chenillo, Gerardo Naranjo, Rodrigo Pla, Diego Luna, Rodrigo Garcia, Mexico

In this portmanteau drawing inspiration from the 1910 Mexican Revolution, ten directors, mostly of the post-Cuaron/Inarritu/del Toro generation, each take 10-minute state-of-the-nation snapshots of their country. The styles and scripts are diverse, but the most successful bracket the film. It opens with Fernando Eimbcke’s black-and-white “The Welcome Ceremony,” which takes place in a small village and addresses the overall theme only obliquely. A small orchestra prepares a welcoming ceremony. An off-key tuba player who can’t stop practicing provides comic relief; he persists even though no one arrives.

Rodrigo Garcia shot the final segment, “7th and Alvarado,” in seductive slow-motion and color. Mexican residents of one LA barrio, who walk in front of big-box stores with their cell phones in hand, are suddenly joined by revolutionaries from a century ago on horseback. Surveying the empty legacy of their brave battle against formidable odds, their eyes express a mild melancholy that is devastating.

Mike Leigh: Shooting London

This is not a film per se. It is rather an occasion, one of the great filmmakers illustrating with clips his approach to shooting the city in which he resides, and explaining how he ties the different neighborhoods and sites into his narratives. Happy-Go-Lucky is one good example. This is as interesting as his much-imitated rehearsal method.

I had the fortune to visit Leigh when he was shooting All or Nothing in 2001 in an abandoned housing project in South London. He can make architecture come alive to move the story along or to tell us something about a character. His unusual background helps explain why he’s comfortable in many different parts of the city. The son of a middle-class Jewish doctor who lived over his clinic in a working-class Manchester neighborhood, Leigh is well acquainted with people on all rungs of the socio-economic ladder. That he has a great eye and an ear for dialogue contributes to his understanding of any part of the city.