Back to selection

Back to selection

Robert Stone, Earth Days

Robert Stone may not be the most famous documentarian, but he is one of the most accomplished and important non-fiction directors working today. The son of eminent British historian Lawrence Stone, Stone was born in England in 1958, but grew up in both the U.S. and Europe after his father left Oxford University to teach at Princeton in 1960. Stone studied history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, graduating in 1980, and thereafter spent seven years turning the subject of his thesis project, the U.S. nuclear tests on the island of Bikini, into the documentary Radio Bikini (1987). The film was Oscar nominated for Best Documentary Feature, and established Stone as a talent to watch. Next he made documentaries on America’s response to Sputnik, Satellite Sky (1989), and the 50s obsession with flying saucers, Farewell Good Brothers (1992), and then continued to explore mid-20th century American history with a massive installation on John F. Kennedy for the JFK Library in Boston. After the faux documentary World War Three (1998), he returned to non-fiction filmmaking with a portrait of Atlantic City, American Babylon (2000). In 2004, he directed the acclaimed Guerrilla: The Taking of Patty Hearst and revisited the subject of JFK with Oswald’s Ghost (2007), a thoughtful examination of the conspiracy theories surrounding Kennedy’s death.

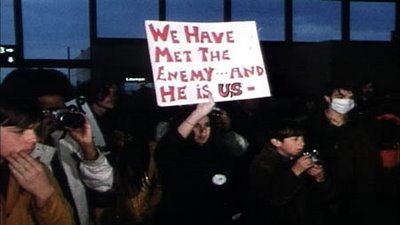

Movies about green issues are very much in vogue at the moment, but Stone’s latest film, Earth Days, is a distinctly different kind of environmental documentary. Instead of focusing on a particular aspect of the planet which is under threat, Earth Days takes a step back to examine the first wave of the environmental movement which, despite being somewhat forgotten now, enjoyed great popularity and achieved much in the late 60s and early 70s. Stone uses the principal figures who first championed green issues – such as politician Stewart Udall, Earth Day organizer Dennis Hayes and Whole Earth Catalog creator Stewart Brand – to focus the narrative. By providing this historical perspective, Earth Days puts the current environmental movement in context and in doing so strikes a cautious note of hope, with the on-camera subjects underlining the achievements of the past as well as the challenges of the future. Stone’s film is also ultimately celebratory, as the expansive cinematography shows the beauty of a planet that is not yet lost, but must be fought for.

Filmmaker spoke to Stone about returning to his cinematic roots, the aesthetics of non-fiction filmmaking, and why he will never work for Court TV again.

Filmmaker: Earth Days begins with a speech on the environment by JFK, which seems to be a nod to your previous film, Oswald’s Ghost.

Stone: It kind of just turned out that way. I was trying to figure out how to introduce the movie without setting the whole thing up and introducing all our characters in the traditional way. I remembered the ending of The Marriage of Maria Braun, the Fassbinder film. It’s a whole movie about this woman in post-war Germany and at the end he flashes photographs of all the chancellors of Germany from World War Two to when he made the movie, and it totally makes you think about what the movie’s about in a completely different way. I always thought that was amazing, so I kind of cribbed that. With Kennedy, it was just a fluke. It turned out that, by virtue of the influence that Stewart Udall had on Kennedy, he was the first president to really address the environmental crisis and population and warn that bad things were coming.

Filmmaker: I sense that the film is very personal to you, although you don’t place yourself in it at all or present anything but an objective view.

Stone: Yeah, it is deeply personal to me. As a small kid, I was profoundly impressed by Earth Day. It really changed my thinking and everybody of my generation that I’ve spoken to all had a similar experience. Take something as simple as littering: before Earth Day, you would take the candy out of the store and throw the wrapper on the ground; after Earth Day, that was taboo. It seems like a small thing, but it was quite a big deal – you just start to think about things differently. As a kid, I was very interested in the space program and watching the men land on the moon and seeing the earth from space. In so many ways, the movie is the story of my life in seeing the environment deteriorate, seeing farmland near where I grew up become housing developments. But at the same time, seeing things get a lot better: I’ve got two small kids, and we go swimming in the Hudson river – when I was kid, that was unthinkable. Air pollution in New York City was just incredibly bad when I was a kid, and now it’s not anywhere near as bad as it was. People forget that this movement arose and actually did succeed in really improving things dramatically. I think there’s this impression that everything’s gotten progressively, but some things have and some things haven’t.

Filmmaker: Earth Day in 1970 was also the starting point for you as a filmmaker.

Stone: Yeah, it the first documentary I made – though you can’t really call it a documentary. It was one roll of Super 8 film that I made with my friends around the time of the first Earth Day, it was about pollution in my little town and it was called Pollution. I still have a copy of it. We just had one roll of film, we edited in camera, and we actually had this crude way of doing sound. We had a tape recorder going and we had this idea we were going to sync it up, but I don’t think we ever actually did. That was my first film. I showed it in class and got a big applause, and I was like, “Ahh, being a filmmaker – this could be kind of cool…” I don’t think my view of the world has changed very much, I’ve just been able to articulate it better over the years. Looking at that film now, it’s surprising how similar my ideas are about the film. So it is kind of ironic that I’ve come back to this all these years later. There’s certainly a direct line from doing that to Earth Days.

Filmmaker: And what did make you come back to this, to explore the roots of the environmental movement?

Stone: Around the time An Inconvenient Truth came out, there weren’t a whole lot of docs like there are now on the environment, but it was certainly in the air that this was a renewed topic of conversation. The whole issue of climate changed was universally agreed upon as a problem, and we were just waiting for Bush to leave. Everybody seemed pretty bummed out about the war, bummed out about Bush, bummed out about 9/11, bummed out about everything. It seemed everybody was making movies about Iraq at that moment and I felt that with the environment there was a sense that a wholly new movement that was arising, a wholly new awakening to the crisis. Remembering back to my childhood, I thought, “Wait, this isn’t true, this is just a rebirth of something that’s been dormant for a long, long time.” I felt that putting all of this in context would be a really good and interesting thing. It just seemed like a completely forgotten story. When most people think about the ’60s and ’70s, they think about Watergate, they think about Vietnam, they think about civil rights, they think about the hippie movement. The whole environmental movement got lost even though it was most profound thing to come out of that period, long term, and it crystallized a lot of the questioning about some very fundamental things about how we organize society. As time’s gone on, with all these environmental documentaries and all these books and television specials, I think people are so overwhelmed. I personally feel overwhelmed with bad about one shocking disaster after the other. I think it’s important to put this all into some kind of larger context – these are all symptoms of a bigger issue.

Filmmaker: I want to talk about the stylistic approach you took with the film, for instance the lack of a narrator.

Stone: Well, I’ve never used narration. I feel as a filmmaker that it’s cheating and I think it puts a distance between you and the audience, like you’re lecturing at them rather than them discovering something themselves. My basic approach to documentary filmmaking is that I think all films basically function the same way, whether they’re documentaries or dramatic feature films, in how they work on an audience. A film succeeds and is at its most satisfying when there’s a process of discovery or a feeling that you’ve watched something and put two and two together and come up with a new way of thinking about something. Rather than been lectured to. With a subject as vast as this, I felt it was vital that it was firmly grounded in personal narrative so finding characters whose personal life journeys mirrored the journey of the film was step one. We set out to follow their trajectory from being kids and understanding the motivation that generation had coming out of the 50s to go out and remake the world, explaining the psychology behind it and then showing what happened and how it all fell apart.

Filmmaker: What about the visual aspects?

Stone: Stewart Brand said that our problem with the environment is one of perception, and if we perceive the problem better then we’ll be more motivated to take action. His whole thing is that technology allows human beings to see the world in a way that we’re not biologically capable of doing. We can go into space, and no other animals can do that. We can go up in an airplane and fly like a bird. We can use film to speed up things, like you can you see a smokestack from a factory spewing smoke. It might look rather benign, but you set up a strop-motion camera for a day and reduce that to a minute and you say, “Oh my God, there’s a huge amount of pollution going into the air.” It’s not faking it, it’s real, it’s just taking out of our human timeframe. The whole thing of technology allows us to see things different became a running theme in the film and really helped us establish a visual palette. A lot of what’s being said is essentially unfilmable – they’re ideas. Also, being able to do CGI was great, like the thing with the tablecloth. Exponential growth is such an inherently unfathomable thing to understand, so I asked Dennis Meadows, “How do you explain this when you’re talking to students?” He told me this thing about the tablecloth, I took it to our effects house and they were actually able to do it. It’s great that you can do that sort of thing now as a documentary filmmaker, which you couldn’t 10 years ago.

Filmmaker: It seems as if you place a lot more emphasis on the beauty of the image and being cinematic than a lot of documentarians these days, which works really well for the subject matter.

Stone: I don’t want this to sound pretentious at all, but my filmmaking hero is Stanley Kubrick. I don’t compare myself to him in any way at all whatsoever, but 2001 is the reason I became a filmmaker. That movie made a huge impression on me as a kid, and I drew on my impressions of it in making this movie, with those long takes with a meditative aspect to them and dealing with these really, really heavy ideas and having a shot that lets you sort of think about an idea. Instead of using 10 shots, use one shot and really linger on it and let an idea unfold – he was really fantastic at that. I was really worried while making this film that young people wouldn’t like it because so many films now are all hyped up and you have to cut every five seconds and it’s like whoosh, bang, boom! This is very not that. We showed 40 minutes of it at the Sundance Institute six months before we finished to a bunch of young filmmakers all in their 20s, and they loved it, they totally got it. That was a huge relief to me. And they liked it because it wasn’t like everything else that they were seeing, because it wasn’t fast and hyped up.

Filmmaker: How do you view yourself as a filmmaker? You’re a history grad, so are you a historian working in film? Or a documentary maker with social and political preoccupations?

Stone: It’s a good question. I’m a filmmaker first, I’m not a political activist who’s using film as a soapbox. When I was younger, I wanted to go off to Hollywood and I’ve long wanted to make dramatic films. I thought I’d end up in Hollywood or making independent feature films, but I ended up doing documentaries. My father was a history professor at Oxford and later at Princeton, so I grew up with that, it’s in my blood. It just seems very natural to me to combine my interest in film, my interest in history, my interest in politics and also my interest in exploring this crazy world that I grew up in. My dad was a social historian who’d written about the English Civil War and he was really fascinated with the 60s when it was happening. He took me around as a little kid: we flew to Paris in May ’68, we sat and watched the entire Watergate hearings together when I was 12 years old. And my mother read me Silent Spring when I was about eight, so I was exposed to all this stuff and I think I spent the rest of my life trying to make sense of it. Fortunately a lot of my generation are also trying to make sense of it, and also so much of it is coming around again.

Filmmaker: How do you choose your subjects? Are you always aware of the balance between your personal interest in a topic and how commercial it will be?

Stone: Well, if you’ve seen Oswald’s Ghost you’ll know that I don’t really care about the commerciality of my projects. Obviously I want to reach as wide an audience as possible, but I also know that I am who I am and I have to make a film that satisfies me. If I start thinking about what an audience is going to think about too much, I’m never going to able to function. Fortunately, I’ve got a niche of people who go to see my films and that’s cool. I’d love to have a hit like Michael Moore, but I don’t think I’m Michael Moore. I don’t have that populist thing in me. I like the gray areas too much. I think in some ways my films are sort of similar. I don’t do this consciously, but I’ve made a bunch of films and looking back, the films that are most me that I’ve made, that are closest to my heart, are about this intersection between fantasy and reality and how we perceive the world. That fascinates me. Being able to work with film, which is such a visual medium, you can really probe that. We all live in our own little fantasy worlds and perceive reality in a different way, and we’re all convinced that our way of seeing reality is “the true way.”

Filmmaker: Talking of the mix of fantasy and reality, you made a faux documentary about World War III which used real archival footage in a fictional context.

Stone: I think anybody who makes documentaries, particularly using archival footage, at a certain point realizes, “Wow, I can do anything with this! I don’t have to tell the truth. I can manipulate things and tell something that’s completely untrue.” It could be as simple as interviewing somebody and then recutting the interview so that they say something that’s the exact opposite of what they actually said. Or doing what I did with World War Three, which is just using real characters and real footage but putting them in a completely fictitious context. Part of it was just poking fun at the medium itself and how easy it is to manipulate people.

Filmmaker: You got an Oscar nomination for Radio Bikini. What was it like to have that level of success so early on?

Stone: It was weird. In one way it was really great, because I sort of got it off my chest. I came from a very high-achieving family so there was a lot of pressure to succeed, and I think if I hadn’t succeeded with that first film, I would have probably done something else with my life. But, it did come very early and I made a lot of bad career decisions. [laughs] You know, I got a little cocky, and it took me a while to regain my stride. But it certainly has been incredibly helpful in raising money: every time I’m introduced anywhere, it’s always as an Academy Award-nominated filmmaker and that’s just a wonderful thing. So it was a blessing to have that at such an early age. And I had a lot of girls. It was definitely good for meeting girls. [laughs]

Filmmaker: What’s the strangest thing you’ve seen, or had to do yourself, during your time in the film industry?

Stone: Jesus, there have been so many… The whole business is strange, it’s strange that I’m even making films, it’s strange that I’m, like, alive and making a living.

Filmmaker: What was your dream job as a kid?

Stone: My dream job as a kid was a Formula 1 race car driver, but I’m partially blind in one eye so it wasn’t an option. But I cherished that idea into sixth or seventh grade, and then I wanted to be an architect and then I wanted to be a filmmaker. And everyone wanted to be Mick Jagger.

Filmmaker: When did you last do it for the money not the love?

Stone: Ah, that’s a good one! The last time I did it for the money was in 1998. I did a television documentary for Court TV. It made me feel like I should get out of this business or start making independent films again. I went and made Guerrilla. I’ll never work for Court TV again, but that’s OK, I don’t want to. [laughs]