Back to selection

Back to selection

Into the Splice

Adventures of a film spectator by Nicholas Rombes

Into the Splice: Let Me In

I went to see Let Me In with low expectations. Like so many, I had seen and been awed by the original Swedish version, Let the Right One In (directed by Tomas Alfredson), whose quiet pacing and lonely stretches of relative silence only made the horror more horrible when it came. An American version, surely, would speed up the pace and overload the naturalistic violence with CGI-generated hyper-energy. On the way to the theater I asked Lisa about this.

“I don’t know,” she said, “give it a chance.”

“But I don’t want to give it a chance. I want to hate it.”

“Then why go?”

“Because I told Scott I was going.”

“Shouldn’t you be open minded?”

“Why?”

That was a real question, if a flip one. More to the point: is it even possible to be open minded, especially when it comes to a remake of a great movie? I got to thinking about the anxiety of influence, not so much the way Harold Bloom meant it (the phrase comes from his 1973 book The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry) as writers struggling against the influence of previous writers, but rather as viewers hindered by our own memories and expectations. In other words, was it even possible for me to give Let Me In a fair shake?

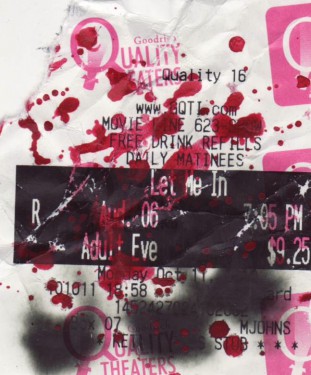

As it turns out, I needn’t have worried. A small theater, down a dark hallway. Two kids in the back row kissing and texting. A guy in a wheelchair up in the front row, his wife or whomever sitting a few rows behind him. And besides Lisa and me, that’s it. It’s a Monday night. As usual, I’ve snuck my camera in the theater, but none of the pictures turn out good. The movie is set in 1983, and there’s Ronald Reagan on the TV talking about evil. The movie doesn’t seem to be using this ironically, as some sort of swipe at Reagan, but literally. Reagan says: “And finally, that shrewdest of all observers of American democracy, Alexis de Tocqueville, put it eloquently after he had gone on a search for the secret of America’s greatness and genius — and he said: “Not until I went into the churches of America and heard her pulpits aflame with righteousness did I understand the greatness and the genius of America. America is good. And if America ever ceases to be good, America will cease to be great.”

Abby (Chloë Moretz), the vampire, is in America, but is she American? She is ancient. Is this why a smile creeps across her face when she sees that Owen (Kodi Smit-McPhee) is reading Romeo and Juliet, because she was alive when it was written? She has been 12-years-old, as she says, for a very long time. To age without aging: does this make one forever young or forever ancient? The beauty and strength of both movies is that neither of them provide the sort of back story that would demystify the dark mystery of Abby’s condition. Questions like how this happened to her, or whether or not she truly loves whomever happens to be the current blood procurer in her life (in the here and now of the movie this part is played by Richard Jenkins, the “Father” although he is not her father). In fact, the tenderest moment of this film occurs not between Abby and Owen, but between Abby and the Not-Father, when, as he prepares to go out and hunt for more blood for her, she reaches up and gently puts the palm of her hand on his cheek, and he rubs his face deeply into it. There are no words spoken. Abby uses him, clearly—he is just one of many, perhaps hundreds of such people she has used throughout history to procure blood—and yet doesn’t love itself involve a level of usury? Love is used to satisfy emotional needs and hunger; Let Me In makes this literal. The love story is not between Abby and Owen, but between Abby and the Not-Father.

Abby (Chloë Moretz), the vampire, is in America, but is she American? She is ancient. Is this why a smile creeps across her face when she sees that Owen (Kodi Smit-McPhee) is reading Romeo and Juliet, because she was alive when it was written? She has been 12-years-old, as she says, for a very long time. To age without aging: does this make one forever young or forever ancient? The beauty and strength of both movies is that neither of them provide the sort of back story that would demystify the dark mystery of Abby’s condition. Questions like how this happened to her, or whether or not she truly loves whomever happens to be the current blood procurer in her life (in the here and now of the movie this part is played by Richard Jenkins, the “Father” although he is not her father). In fact, the tenderest moment of this film occurs not between Abby and Owen, but between Abby and the Not-Father, when, as he prepares to go out and hunt for more blood for her, she reaches up and gently puts the palm of her hand on his cheek, and he rubs his face deeply into it. There are no words spoken. Abby uses him, clearly—he is just one of many, perhaps hundreds of such people she has used throughout history to procure blood—and yet doesn’t love itself involve a level of usury? Love is used to satisfy emotional needs and hunger; Let Me In makes this literal. The love story is not between Abby and Owen, but between Abby and the Not-Father.

The longer the movie went, the less there was to hate about it. The man in the wheelchair’s wife went to get some popcorn during the scene when the Not-Father gets terribly burned, and part of me was glad she missed it. She needs to be protected from seeing something like that, I thought—she has enough trouble in her life. Then there was a silent stretch in the film, and we could hear each other in the theater. The teenaged couple a few rows down leaned so close to each other that they became one person.

“What about when she scampers up trees like a J-Horror girl?” I whispered to Lisa.

“That’s okay. She’s like a bat,” she said. “It fits.”

Let the Right One In and Let Me In are movies of subtraction. There are no grand speeches by vampires about who they are, or what they want. Except for food. Abby just needs food. And there are no heroic vampire chasers or killers. The policeman (Elias Koteas) is persistent but ineffectual. He is in a situation in which there is no context, no framework, no norms. He believes he is on the trail of evil (a serial killer) but what he is chasing is beyond good and evil. The vampire is simply hungry. In certain scenes, her stomach growls. We know that hunger. She doesn’t kill for sport, but for food.

Let the Right One In and Let Me In are movies of subtraction. There are no grand speeches by vampires about who they are, or what they want. Except for food. Abby just needs food. And there are no heroic vampire chasers or killers. The policeman (Elias Koteas) is persistent but ineffectual. He is in a situation in which there is no context, no framework, no norms. He believes he is on the trail of evil (a serial killer) but what he is chasing is beyond good and evil. The vampire is simply hungry. In certain scenes, her stomach growls. We know that hunger. She doesn’t kill for sport, but for food.

The walls of our theater shake from the explosions of the movie in the next theater over. They seep into our world, and instead of breaking the spell, they intensify it. It’s as if the fatal doom of the ending echoed throughout the Cineplex, which is practically deserted when we leave. Behind the concession stand, a girl with blue hair sweeps up the popcorn from floor and chews gum, moving in slow motion. The restroom lights are off. The man in the wheelchair and his wife beat us to the exit, but it’s so dark out, they hesitate. The make-out teenagers are there, too. For a moment we all wait, then move out into the black night and go our separate ways, checking, I’m sure, the back seats of our cars before we climb in.

Nicholas Rombes is author of Cinema in the Digital Age and A Cultural Dictionary of Punk, 1974-1982. His work has appeared The Oxford American, the n+1 Film Review, and McSweeney’s Internet Tendency. His column, 10/40/70, appears at The Rumpus. He can be found at nicholasrombes.blogspot.com.