Back to selection

Back to selection

REMEMBERING THE PASTS AND FUTURES OF “REQUIEM FOR A DREAM”

This blog post is part of the Requiem 102 experiment: on the occasion of the 10th anniversary of Darren Aronofsky’s Requiem for a Dream, different writers are each looking at the film through the prism of specific frames, one from each minute of the film. I’ve been assigned minute four. Follow all the responses here.

For me, the most memorable scene in Darren Aronofsky’s Requiem for a Dream is not in the movie but in the script. I had read it before the film’s pre-production, and the scene in which dealers line up for a new shipment of drugs after the city’s dry spell took place not in the back of a supermarket but on the beach. A ship sat on the horizon, a small boat sped to shore, dealers set up a card table on the sand, and a line of addicts stretched for miles to get their fix.

For me, the most memorable scene in Darren Aronofsky’s Requiem for a Dream is not in the movie but in the script. I had read it before the film’s pre-production, and the scene in which dealers line up for a new shipment of drugs after the city’s dry spell took place not in the back of a supermarket but on the beach. A ship sat on the horizon, a small boat sped to shore, dealers set up a card table on the sand, and a line of addicts stretched for miles to get their fix.

A great scene — too great in scale for a $4.5 million independent film. I remember seeing Requiem for a Dream at its Cannes premiere, at midnight. I was sitting way up in that huge room at the Palais, where the seats are raked so steeply you feel like you’re going to succumb to vertigo and fall into the orchestra. I waited for that scene, was disappointed when it didn’t arrive, but had forgotten all about it by the time the film’s assaultive third act, with its accelerating editing rhythms, had finished.

With Requiem for a Dream Aronofsky created a ruthless symbolic universe bordered by the contours of the film’s formidable sense of style. But unlike many Hollywood films where style is an end to itself, here the production design, cinematography and even the glamour casting serve only to give the film’s ideas clarity. Hermetically sealed, Aronofsky’s film sidearms Hubert Selby, Jr.’s junkie tale away from the conventions of the genre, the grey, grainy streets filled with Ratso Rizzo clones, making clear that the story is not about drug addiction but the ways in which consumer capitalism mediates not only our daily lives but our ability to rationally conceive of better and certainly possible futures. From an interview I did with Aronofsky in 2000: “Selby said that one of the things the movie is about is the length we go to to escape our realities. When we chase our dreams and live in the future, we create this hole in our present, and we use anything to fill that vaccum: TV, sex, tobacco, drugs, hope — they’re all there just to fill the hole.” (Two days after the mid-term elections, emphasis added…)

The frame I’ve been assigned occurs four minutes into the film. Harry (Jared Leto) and Tyrone (Marlon Wayans) have just stolen Harry’s mom’s television and are wheeling it down the street to a pawn shop. For Harry’s mom, Sara, (Ellen Burstyn), this is a regular occurrence, both vexing — she loves her TV — but also reassuring. By regularly buying back the television, she funds her son’s drug addiction, locating their love within the economy of this ritual while not having to acknowledge its nature. Harry and Tyrone wheel the TV past the Cyclone roller coaster at Coney Island, suggesting the thrill ride the movie — in fact, all of Aronofsky’s movies — will become. Aronofsky: “My whole thing really comes from growing up in Coney Island and riding the Cyclone. The Cyclone taught me that the action must keep coming at you.”

Elsewhere in that interview, Aronofsky told me that he conceived the film as a horror movie. He said he charted out the four main characters’ arcs on a series of graphs. “I realized that the enemy of these characters — addictions with a capital “A” — was actually the hero. I realized that Requiem is a monster movie, and the monster is Addiction. It’s not a monster movie where the monster is the hero. The monster is in the heads of the characters, and it slowly destroys their spirit and their love. So, for every scene, I said to the whole creative team, ‘Where is Addiction in this scene, what is Addiction thinking, how is Addiction succeeding, and how can we portray the subjective vision of Addiction.’”

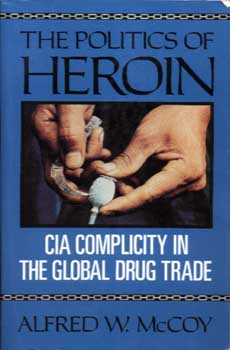

But back to that boat. Aronosky said he purposefully made Requiem’s drug unclear. For me, as for most people, I believe, it reads as heroin. The boat most likely would have been carrying drugs originating in Afghanistan, and if the city was dry in late 2000, at the time of the film’s release, it would have been due to the Taliban’s shutdown of the country’s opium trade beginning that year. In 2000, remarks delivered at the U.N. on behalf of the executive director of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime cited a 94% decrease in opium production following the Taliban’s ban on poppy production. But following the invasion of Afghanistan, the U.S. government and the U.N. both claimed that this Taliban crackdown was intended not to shut down the country’s drug trade but to engineer “an artificial shortfall in supply” — even though there was no evidence of stockpiling. Heroin production has soared there since the invasion of Afghanistan, inflating that nation’s rebuilding economy and providing money to Western criminal syndicates as well as more easy fixes for today’s Harry and Tyrones. Meanwhile, the post 9/11 security state has taken care of the dream reshaping business. (For more, read Alfred W. McCoy’s The Politics of Heroin: CIA Complicity in the Global Drug Trade.)

But back to that boat. Aronosky said he purposefully made Requiem’s drug unclear. For me, as for most people, I believe, it reads as heroin. The boat most likely would have been carrying drugs originating in Afghanistan, and if the city was dry in late 2000, at the time of the film’s release, it would have been due to the Taliban’s shutdown of the country’s opium trade beginning that year. In 2000, remarks delivered at the U.N. on behalf of the executive director of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime cited a 94% decrease in opium production following the Taliban’s ban on poppy production. But following the invasion of Afghanistan, the U.S. government and the U.N. both claimed that this Taliban crackdown was intended not to shut down the country’s drug trade but to engineer “an artificial shortfall in supply” — even though there was no evidence of stockpiling. Heroin production has soared there since the invasion of Afghanistan, inflating that nation’s rebuilding economy and providing money to Western criminal syndicates as well as more easy fixes for today’s Harry and Tyrones. Meanwhile, the post 9/11 security state has taken care of the dream reshaping business. (For more, read Alfred W. McCoy’s The Politics of Heroin: CIA Complicity in the Global Drug Trade.)

One more thing — there is also a Nathan’s hot dog sign in the frame I’ve been assigned. Online I learned that Nathan’s got its start when Nathan Handwerker, an employee of a rival hot dog vendor, and his wife Ida went into business for themselves. They undercut their former employer’s price by 50%, selling hot dogs for five cents, not ten. Because hot dogs were viewed as health risks at the time, they convinced their customers that their food was safe by outfitting their servers in surgeon’s smocks.

One more thing — there is also a Nathan’s hot dog sign in the frame I’ve been assigned. Online I learned that Nathan’s got its start when Nathan Handwerker, an employee of a rival hot dog vendor, and his wife Ida went into business for themselves. They undercut their former employer’s price by 50%, selling hot dogs for five cents, not ten. Because hot dogs were viewed as health risks at the time, they convinced their customers that their food was safe by outfitting their servers in surgeon’s smocks.