Back to selection

Back to selection

“WAR DON DON” AT STRANGER THAN FICTION

While introducing War Don Don at last night’s Stranger Than Fiction, SXSW programmer Janet Pierson said that while many great documentaries were submitted to last year’s festival, there were few with the “clarity” of Rebecca Richman Cohen’s directorial debut. It was a sentiment later echoed by Raphaela Neihausen, the executive director of Stranger than Fiction who praised Richman Cohen for her ability to “break down a complex issue” but still keep the “nuance.”

While introducing War Don Don at last night’s Stranger Than Fiction, SXSW programmer Janet Pierson said that while many great documentaries were submitted to last year’s festival, there were few with the “clarity” of Rebecca Richman Cohen’s directorial debut. It was a sentiment later echoed by Raphaela Neihausen, the executive director of Stranger than Fiction who praised Richman Cohen for her ability to “break down a complex issue” but still keep the “nuance.”

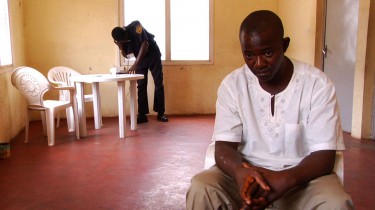

Three years in the making, War Don Don follows the UN Special trial of Issa Sesay, one of the leaders of the RUF, an incredibly violent rebel group in Sierra Leone. Although we know that Sesay will be convicted from the very beginning, Richman-Cohen finds an incredible amount of drama by questioning whether or not that conviction was fair. Structured like a trial, War Don Don follows both the zealous prosecutor who sees no grey and the sympathetic defense attorney (with movie star good looks) who sees nothing but. As the two sides construct their competing versions of Sesay’s story, we realize that the truth about Sesay is probably forever beyond our grasp. One of the most viscerally compelling documentaries of the year, it will leave you haunted.

I spoke to Richman-Cohen before the screening.

Filmmaker: I noticed in your biography that you have an unusual background for a filmmaker – you went to law school, not film school. When did you decide you wanted to make documentaries?

Richman-Cohen: In law school, I worked at the court where the trial takes place. During that time, I came to know people who were involved in the trial, and I thought they were fascinating. Having worked there, I thought I might have some great access…Also, I felt that the subject of international criminal justice, these trials and the complexities of how they operate, had been largely ignored. The story wasn’t going to get told unless I told it.

Filmmaker: As a first time filmmaker, how did you get started?

Richman-Cohen: It wasn’t that I had no filmmaking background. I had worked as an assistant editor on Fahrenheit 911 before I went to law school, so my first step was to call my co-assistant editors. Most of the crew of War Don Don were people who had worked with me on Fahrenheit.

Filmmaker: Making a feature doc is a big life commitment. How did you know that you had a story that could fill out a feature?

Richman-Cohen: In order to get anyone to get to watch a film, it has to have people that you care about. Having worked at the court, I was moved by how both the prosecution and the defense were very passionate about their work even though they were pursuing very different means and very different ends. Also, I had worked on a trial team defending an accused war criminal and people had very bad reactions to that. So in a way my film was a response to people’s reactions –War Don Don is unique in that it gives the defense and the perpetrators a powerful voice.

Filmmaker: Was access to either the court or Issa Sesay an issue?

Richman-Cohen: We had fierce questions of access. This is a film about an accused war criminal, and it was uncertain whether we would have access to him or not. We had to ask ourselves how to make a film that orbits around a human being without getting to know who they are. Our plan was to make it like a trial because that’s what a trial does. On one of the last days of the shoot, were allowed to interview him. It was a combination of good will on behalf of people in the special courts and people who pushed for transparency and just plain old luck.

Filmmaker: Going into the project, did you have an idea of how you were going to structure your story or did that become clearer while you were filming?

Richman-Cohen: We knew we were making a film about a trial. That gave us a clear beginning, middle and end. There were certainly surprises on the way…We decided structurally to start with conviction. We didn’t want to create false suspense when we knew that he would be convicted – so we decided to create the suspense on what his sentence would be. We wanted it to take into account how hard it is to come up with a fair sentence. The real surprise is the sentencing, the climax of the film.

Filmmaker: Were you fundraising while you were shooting?

Richman-Cohen: We were fundraising the whole time…We had a number of great foundations that came in at important times because the trial didn’t wait for us to fundraise. Pitching a film about Africa, so many people roll their eyes before you even say the word Africa. There are some issues that people have an automatic negative response.

Filmmaker: One of the things that keeps people fundraising is supporting an office and an office staff. Did you set up an office to support your project?

Richman-Cohen: We kept it very lean. We spent most of the time editing out of our apartment except for July through January, the last seven months, we edited out of DCTV. My editor, Francisco Bello was making a film with Jon Alpert. Their office was in DCTV so I could be near Francisco, so I got into editing while he was still working on the film. It’s wonderful to be in the space with other filmmakers. Its just a very active place, an easy place to rent gear. To be in a community with other filmmakers was a gift for us.

— Mary Anderson Casavant