Back to selection

Back to selection

Into the Splice

Adventures of a film spectator by Nicholas Rombes

Into the Splice: Black Swan

Things didn’t bode well from the beginning. The crowd in the theater was restive. People shifted uncomfortably in their seats even before the movie began. I was alone, and sat in the back, the projector whirring somewhere above and behind me. But that was only the beginning. As it turns out, I had been editing Alla Gadassik’s remarkable video-essay for the Requiem // 102 project, and had learned of an obscure Italian Jennifer Connelly film from 1988, Etoile (directed by Peter Del Monte), which also happens to be a nightmarish film about Swan Lake that also features a monstrous black swan. Daronofsky + Connelly + Requiem + Black Swan. All these things swirling in my head, in the same way that each of us enters the dark of a movie theater with fragmented narratives in our heads, in hopes that the movie we are about to see will transport us outside of ourselves, into some other world.

And that’s the battle: between ourselves and the screen. We need big screens—forget scrawny computer or iPad or whatever screens—to take us out of ourselves. Black Swan on the big screen, not some puny screen six months from now.

In Robert Coover’s 1987 short story “The Phantom of the Movie Palace” the lonely projectionist, playing films to an empty theater night after night, takes matters into his own hands, becomes his own DJ mixer of visuals: “Sometimes, when one picture does not seem enough, he projects two, three, even several at a time, creating his own split-screen effects, montages, superimpositions. Or he uses multiple projectors to produce a flow of improbable dissolves, startling sequences of abrupt cuts and freeze frames like the stopping of a heart.” This was Coover’s pre-digital fevered dream, a mix-tape of styles and symbols, played out mashed-up on the big screen. In a similar vein, Black Swan jumps tracks between genres, shape-shifting in the same way that Nina shape-shifts.

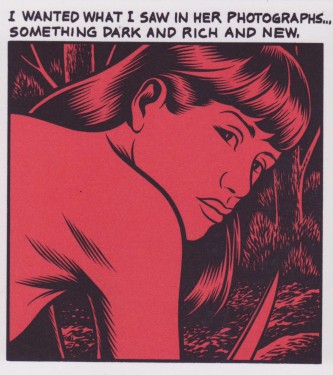

And so: there was trouble in the theater. A weird vibe. Just before the film began, a group of hooded teenagers entered and sat in the front row. Maybe they weren’t teenagers. Beneath their hoods, a dim red glow, like the glow of the EXIT signs. Something wrong with the way they moved, more like crones than kids. A black hole aura. One of them took off her sweatshirt, and shook her hair. In the glow of the previews, and still shining in some sort of terrible red light, I imagined she looked like the girl in Charles Burns’s graphic novel X’ed Out. The same red as Natalie Portman’s eyes later in the film. A terrible mix of associations, played out on the screen in a movie that almost flies apart under the contradictions of a controlled hysteria.

And so: there was trouble in the theater. A weird vibe. Just before the film began, a group of hooded teenagers entered and sat in the front row. Maybe they weren’t teenagers. Beneath their hoods, a dim red glow, like the glow of the EXIT signs. Something wrong with the way they moved, more like crones than kids. A black hole aura. One of them took off her sweatshirt, and shook her hair. In the glow of the previews, and still shining in some sort of terrible red light, I imagined she looked like the girl in Charles Burns’s graphic novel X’ed Out. The same red as Natalie Portman’s eyes later in the film. A terrible mix of associations, played out on the screen in a movie that almost flies apart under the contradictions of a controlled hysteria.

During the movie, others in the theater were jumpy. An elderly couple in front of me scoffed when Nina bites Thomas’s lip during a kiss. Somebody clapped when Lila kissed Nina. The sound cut out for about ten seconds during the scene when the lights cut out at the rehearsal space. During the strobe-light club scene, someone stood up, put on his coat, and left the theater. By the end of the movie my heart was racing. I wanted Nina to stay a black swan, a real black swan, and not just in her head. I wanted Darren Aronofsy to become the other D.A., Dario Argento, and to push Black Swan all the way, far beyond the “it was all in her head” clichés, so that the madness was not Nina, but the film itself.

Nicholas Rombes is author of Cinema in the Digital Age and A Cultural Dictionary of Punk, 1974-1982. His work has appeared The Oxford American, the n+1 Film Review, and McSweeney’s Internet Tendency. His column, 10/40/70, appears at The Rumpus. He can be found at nicholasrombes.blogspot.com.