Back to selection

Back to selection

FILMMAKER’S GUIDE TO HALLOWEEN HORROR

For those of you planning a Halloween viewing party, the staff of Filmmaker has compiled thoughts on seven films guaranteed to generate chills.

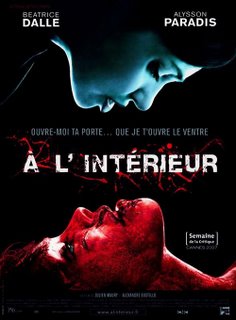

Inside. If you watch a lot of horror films, at a certain point you being to feel that you’ve seen it all. I did… at least until I saw Inside. This French shocker is part of a new wave of Gallic horror that includes films like Haute Tension, Frontieres, Calvaire and Them. For me, it’s the most extreme and transgressive of the bunch, mostly due to its relentless, remorseless elaboration of its queasy premise: a pregnant woman, who we are introduced briefly when she’s involved in a car accident, finds herself stalked at home on Christmas Eve, the morning before she’s due to be admitted to the hospital to deliver her baby. The film owes quite a bit to the classic “woman alone in a house” genre that began with Wait Until Dark, but here the real threat is felt in utero as Beatrice Dalle plays a black-clad stalker whose designs on our heroine’s baby are expressed in three short words: “I want one.” When so many horror films don’t go far enough, Inside may actually go too far. No foreshadowing, implication, or theoretical possibility contained within its premise goes unexplored. There are CGI fetus reaction shots and by the middle of the film there has been as much blood and strewn tissue as most films manage in not just their first installment but also their sequels.

I argued with someone who felt that if this film had been directed by someone like Gaspar Noe it would have been a lot better because it wouldn’t have felt like a horror film. And while Inside is very well acted and has moments of real subtlety, it is, definitely, a horror film — the filmmakers are very confident pushing the limits of the genre. I’m fine with that. The genre trappings here — the cutting, the camera placement, even the film’s strange detour into zombie-ism at one point — provide much needed elements of comfort in what remains an incredibly brutal film. Yet despite the escalating gynecological gore and its ballsy, blantant metaphorical mindfucks (Christmas Eve, c’mon!), , the film ends on a chilling poetic note, with one plot twist managing to do something I would have never have guessed possible: conclude with sympathy for Dalle’s veangeful murderess. — Scott Macaulay

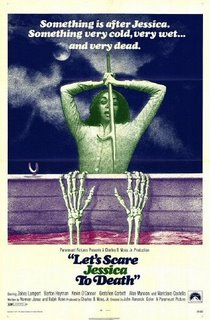

Let’s Scare Jessica to Death. Perhaps best known now for his 1973 hit, Bang the Drum Slowly, director John D. Hancock preceded that film with cult favorite Let’s Scare Jessica to Death. Once a late-night TV staple, this brooding, dreamy mind-fuck is perhaps one of the best ’70s vampire films, with nary a fang to be seen. When a young married couple and their best friend settle into their New England home to live off the land, already depressed Jessica begins seeing strange figures and hearing voices: is she imagining it all, or is something really in the lake behind the house? A potent meditation on the death of hippie culture, Hancock delivers the chills. The final moments will stay with you long after you’ve seen it. — Andre Salas

The Evil Dead. Sam Raimi’s debut feature has not only become a cult classic but is a blueprint on how to make a low-budget horror film. Set in a remote cabin in the woods, a group of college friends inadvertently unleash evil spirits after playing a mysterious tape recording. In a role that would make him a B-movie legend, Bruce Campbell plays the subdued pretty boy Ash who after all the others are killed off is left to fend for himself against the spirits. Legendary for Raimi’s unconventional camera work and mixing gory horror with slapstick comedy, the film spawned the sequel/remake The Evil Dead II and the third installment Army of Darkness. — Jason Guerrasio

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. Although I’m not sure I could put together a list of what I consider to be the 10 greatest movies of all time, I would have no remorse about sliding Tobe Hooper’s 1974 debut, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, alongside the likes of 2001: A Space Odyssey, 8 1/2 and Apocalypse Now. All great movies do not have to be classy or intellectual; they must be singular, brilliantly executed and leave a lasting influence — and by those standards, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre sits quite comfortably on a throne of its reputation.

Chain Saw is an unapologetically ugly film. It has no greater agenda than to take the viewer on a tour through the most rancid elements of human derangement. Some have argued that it’s really a parable about the Vietnam War or about the disintegration of the American family; to me, it’s simply a clash between evolved modern frivolity and an uncivilized throwback to humanity’s base (not unlike Apocalypse Now). But none of that really matters because the movie’s primary intent is not intellectual but visceral.

In the early-to-mid-70s, there was a trilogy of independently produced pictures, of which TCM was one (the others were Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left and The Hills Have Eyes — though some would also add George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead), all shot in 16mm with budgets ranging from $90-300k, that effectively merged exploitation pictures with art films. I think Craven’s pictures were more serious in their thematic construction, pitting civilization against uncivilized instincts (Last House is based on Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring), however, in terms of pure cinema, I find Hooper’s to be more unique and skillfully made by a wide margin.

For a long time, the only version available was on a scratched, grainy, decomposing VHS tape — and the corrosion of the picture heightened the film’s aesthetic reputation of realism; it truly felt like an underground snuff film. Once, about 14 years ago, I caught a Halloween double-feature of Chain Saw and Living Dead, and on the way out a woman remarked that it was the goriest movie she’d ever seen. In fact, Chain Saw shows very little on-screen violence — yet it’s so masterfully directed, people are regularly convinced of the opposite.

Often lost amongst the discussions of realism and violence is just how well thought out the picture’s visual strategy is. Beyond the famous dolly shot of Pam walking up to the house or the wide blue sky master of the van pulling up to the Hitchhiker, Chain Saw sticks to a consistent set of tactics where the camera is shifting between close tracking shots of the characters (subjectively putting the audience in the center of the action) and distant wide shots (placing the viewer in a helpless, objective position). This strategy can best be seen in Pam’s murder and also during the finale, where the camera keeps juxtaposing handheld shots of Sally trying to climb onto the back of a stalled pickup with long-lens masters that force the audience to watch the events like spectators watching sports on TV. Chain Saw, unlike most horror/exploitation, is a legitimately well-made film, crafted with a true understanding of cinema and its language, regardless of its ugliness. — Jamie Stuart

Halloween. John Carpenter’s original 1978 Halloween is one of the most effective horror films ever produced. It’s a beautifully distilled meditation on the eternal, confounding nature of pure evil. For many years it was the most profitable independent feature in history, and it was ripped-off, sequalized and even remade — but none of the subsequent efforts were made with the same level of artistry…or simplicity.

Halloween. John Carpenter’s original 1978 Halloween is one of the most effective horror films ever produced. It’s a beautifully distilled meditation on the eternal, confounding nature of pure evil. For many years it was the most profitable independent feature in history, and it was ripped-off, sequalized and even remade — but none of the subsequent efforts were made with the same level of artistry…or simplicity.

Horror, in my opinion, always works best when it’s set in a definable reality (Jaws, The Exorcist). This way, a relatable everyday is established first before the “monster” invades. And what could be more relatable than teenaged babysitters in the suburbs on Halloween night? Furthermore, Halloween is decidedly un-slick, unlike most modern horror films — it’s ruthlessly mundane, just like the suburbs are.

In terms of the artistry of its craft, Halloween boasts not just one of the most memorable, effective scores in the history of the medium, but it also features some of the most exquisite uses of CinemaScope compositions ever. And by ever, I mean EVER. In fact, the classic score is often used to underline specific moments where a character will be occupying the foreground totally unaware as The Shape appears on the opposite side of the frame in the background.

Halloween is a real film-buff picture, filled with references to Hitchcock, Welles and Hawks. The famous opening shot (technically two shots) that shifts from outside to inside to a murder then back outside is an admitted homage to the opening of Touch of Evil. This shot was accomplished with one of the earliest uses of the Panaglide, Panavision’s version of the StediCam, and it not only beat Stanley Kubrick’s gliding camera in The Shining to the screen by two years, but it also beat Martin Scorsese’s famous Copa shot from Goodfellas by a dozen years.

Unfortunately, Halloween became a victim of its own success. After three decades of sequels and imitations its freshness has probably worn for a lot of people. Not for me. Dated setting aside, I’d still argue that it might be the scariest picture ever made. Turn off the lights and hit play. The moment the theme begins against black, before the first image is seen, you’re completely hooked. And completely creeped out. — Jamie Stuart

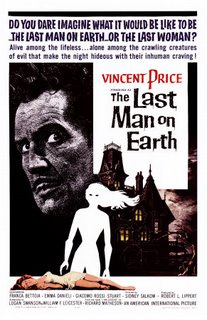

At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul. The first horror film to come out of Brazil, this demented story of an undertaker named Coffin Joe who is in search of a woman to bear his son stars Brazilian actor José Moijca Marins in the lead role, he also directed and wrote the film. Marins’s performance as Coffin Joe is a tour-de-force. His beady eyes, blood-curdling delivery, unibrow and shockingly long fingernails (which he spent years to grow out) will certainly make you lose sleep. Coffin Joe would return in the sequels This Night I Will Possess Your Corpse and Embodiment of Evil, but the first installment introduces the world to one of the most Machiavellian characters in horror. — Jason Guerrasio The Last Man On Earth. In the same year, 1964, Coffin Joe was making his big screen debut, directors Ubaldo Ragona and Sidney Salkow’s adaptation of Richard Matheson’s post-apocalyptic sci-fi book I Am Legend starring Vincent Price was released. The first of what would become a string of adaptations/inspirations over the decades of Matheson’s novel (1968’s Night of the Living Dead, 1971’s The Omega Man, 2002’s 28 Days Later, 2007’s I Am Legend), Price plays a doctor who spends his days seeking out and killing the vampires that have taken over the world and hiding out in the evenings while they are awake, hoping the next day will bring a sign of another normal being like him. A precursor to the soon-to-be popular zombie genre, Matheson took an early pass at the screenplay but asked for his name to be taken off after being disappointed by the final version. Regardless, it’s one of Price’s best performances. — Jason Guerrasio

The Last Man On Earth. In the same year, 1964, Coffin Joe was making his big screen debut, directors Ubaldo Ragona and Sidney Salkow’s adaptation of Richard Matheson’s post-apocalyptic sci-fi book I Am Legend starring Vincent Price was released. The first of what would become a string of adaptations/inspirations over the decades of Matheson’s novel (1968’s Night of the Living Dead, 1971’s The Omega Man, 2002’s 28 Days Later, 2007’s I Am Legend), Price plays a doctor who spends his days seeking out and killing the vampires that have taken over the world and hiding out in the evenings while they are awake, hoping the next day will bring a sign of another normal being like him. A precursor to the soon-to-be popular zombie genre, Matheson took an early pass at the screenplay but asked for his name to be taken off after being disappointed by the final version. Regardless, it’s one of Price’s best performances. — Jason Guerrasio