Back to selection

Back to selection

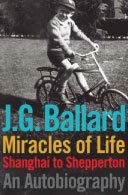

J.G. BALLARD’S WAY OF LIFE

I believe in the power of the imagination to remake the world, to release the truth within us, to hold back the night, to transcend death, to charm motorways, to ingratiate ourselves with birds, to enlist the confidences of madmen.

I believe in the non-existence of the past, in the death of the future, and the infinite possibilities of the present.

That’s J.G. Ballard from his prose poem, “What I Believe” (1984), as quoted in Mark Dery’s February essay in the L.A. Weekly on Miracles of Life: From Shanghai to Shepperton, the author’s memoir, currently out in the U.K. For anyone remembering or thinking about Ballard on the occasion of his passing away, Dery’s piece is essential. An excerpt:

Ballard’s genius lies in his metaphoric use of scientific jargon and an antiseptic tone, somewhere between the dissecting table and the psychopathic ward, to psychoanalyze postmodernity. Long before deconstructionists like Jacques Derrida were slinging around references to the “decentered” self, Ballard is talking, in his trenchant introduction to Crash (1973), about “the most terrifying casualty of the century: the death of affect” and about “the increasing blurring and intermingling of identities within the realm of consumer goods.” Before postmodernists like Jean Baudrillard were announcing the Death of the Real and its unsettling replacement by uncannily convincing media simulations, Ballard is claiming that “we live in a world ruled by fictions of every kind” — advertising, “politics conducted as a branch of advertising,” P.R. “pseudo-events,” et al. — where “Freud’s classic distinction between the latent and manifest content of a dream, between the apparent and the real, now needs to be applied to the external world of so-called reality.” And before neo-Marxists like Fredric Jameson and Mike Davis were pondering the deeper meanings of the Westin Bonaventure Hotel and Frank Gehry’s Hollywood library, Ballard is pondering the psycho-spatial effects of the built environment: the experience of swooping around a freeway cloverleaf; of walking through a cavernous, empty multistory parking garage; of waiting, alone, in an airport departure lounge; of walking the privately policed streets of an obsessively manicured exurban community. How, Ballard wonders, is our sense of our selves as social beings and moral actors — our very understanding of what it means to be a self — being transformed (deformed?) by the whip-lashing hyperacceleration of technology and the media, the blurring of the distinction between real and fake? Ballard was the first to ask how we became posthuman.