Back to selection

Back to selection

Five Questions with Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me Director Drew Denicola and Producer Danielle McCarthy

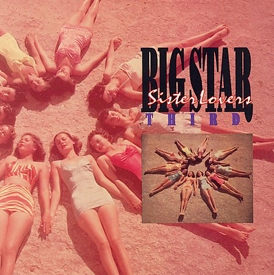

If you recognize the name Big Star, chances are you’re already a fan. Considered by many grandfathers of indie-rock, the band formed in Memphis, Tennessee in 1971. A precarious time for music, Big Star released their first two albums (the dual pop masterpieces #1 Record and Radio City) just as the major labels were riding the post-60s hangover away from creative ingenuity and towards corporate rock excess. Beleaguered and disheartened by their lack of mainstream success, Big Star went on to release one more album, the frustrated and nihilistic chronicle of artistic disintegration Third / Sister Lovers.

Co-founder Chris Bell died in a car accident in 1978 at the age of twenty-seven. Alex Chilton, the band’s lead singer and foremost creative force, pursued a solo-career, acted as a mentor for many of his disciples (including The Replacement’s Paul Westerberg), and watched as the Big Star Cult grew. Chilton passed away in March of 2010 (at the age of fifty-nine).

The reformed lineup of Big Star was scheduled to play a show at SXSW just days later, a show that was quickly transformed into an impromptu tribute to the late Chilton. Now, two years later, director Drew DeNicola and producer Danielle McCarthy are at the festival presenting a special in-progress cut of their new documentary Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me.

Filmmaker: How did you first discover Big Star? And at what point did you know you wanted to make a documentary about the band?

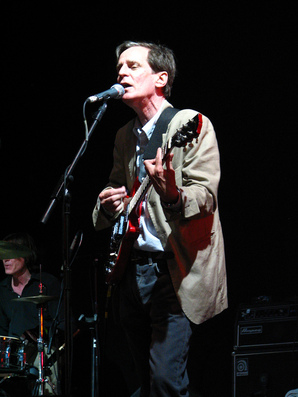

DeNicola: I was in college radio in New Orleans and the Ryko reissue of Third/Sister Lovers was on the shelf. Up until then I had heard they were a Power-pop band–which wasn’t a genre I was all that interested in (that’s another topic of debate in the film). But Third/Sister Lovers sounded totally contemporary, even in 1994. Alex Chilton was living in New Orleans then and I went to see him play. He was doing this sort of lounge act, and having a lot of fun onstage. It made no sense to me. I was young and brooding and really serious about my music. Later, I got into more of Alex’s music and everything Big Star-related, but it was Third/Sister Lovers that opened the door for me.

The point I knew I wanted to make the doc was when I met Danielle McCarthy and she asked me to help her out. At that point she had a stack of DV tapes from a trip to Memphis she did a year or two prior. I said to her, “How has no one already tried to do this?”

Once I took the project on I started to think about how to make a documentary about a band that had almost no career, different members for each record, and very little archival material. I think I realized I wanted to make this doc when the story led to larger topics like Memphis’ roots, the roots of Rock and Roll, and the idea of a band appreciated in absentia. It made this film very different from a mere chronology of a band.

And also, one note: Olivia Mori joined in 2010, once we’d secured funding. At that point I knew we had enough funds and dedicated staff to bring this film to completion. Olivia produced all our shooting in Memphis. She has since been assistant directing with me and getting the story together in the editing room. Once we got to Memphis and met a lot of the people there it became less about getting information from the interviews and more about casting our storytellers and bringing them to life as characters in the film.

McCarthy: I probably first heard a Big Star song from my father who had the This Mortal Coil albums but had no idea who Big Star was at that point. A few years later when I was in college, a friend of mine played “Kangaroo” on an acoustic guitar and I was hooked. And then a few years after that I went to Memphis for the first time and really got to hear the story of Big Star from my friend Winston Eggleston (William Eggleston’s son). I realized what an amazing story it was – how connected it was to so many other musicians and artists I loved. I just felt that Big Star really deserved to have its story told.

Filmmaker: Big Star is considered something of the ultimate cult band. In your teaser trailer, more than one fan describes them as a “mystery.” What is it about their music that’s created this vast mythology?

DeNicola: We definitely ponder the idea of a “cult band” in the film. The writer Lenny Kaye talked about the potency of a more marginal audience; for many it’s almost a religion. Talking Big Star was like speaking in code in the ’70s and early ’80s. However, I think Big Star’s case is unique because unlike say The Grateful Dead or Captain Beefheart, the cult was gathered around the record player or passed tenth- generation cassettes to each other. Few people ever saw them play. So in a way the Big Star cult is almost more exclusive.

Also, one element of the story that’s been hard to get across is that cult bands are usually sort of avant-garde or musically challenging, while Big Star’s music is more like a revival or celebration of everything that was loved about popular music in the mid-’60s. The music is so listenable. But I believe that the cult grew out of the repeat listening– there’s darkness and desperation between the shimmering guitar lines and anthemic choruses that make the music emotionally complex. This has really allowed the Big Star catalog to rise to the level of “durable music” for so many listeners over the last 30 years.

But there was also just incredible poignancy in the weird space that Big Star occupied back then. For many years before they were a cult band they were a “critic’s band.” And there’s a scene in the film about how this came about. In the early ’70s a new breed of rock writer was coming around in opposition to the decadence of corporate rock and Rolling Stone Magazine. The promoters at Ardent sought out people like Lester Bangs and Nick Tosches and the entire staff of CREEM Magazine, eventually gathering them all in Memphis for a wild weekend to see Big Star perform, all expenses paid. This assembly of over one hundred rock writers in 1973 cemented Big Star as a cause celebre for rock critics, and they continued to carry the torch through the ’70s.

Filmmaker: Alex Chilton’s had an especially multifaceted career – from his early commercial success with the Box Tops to his groundbreaking work with Big Star, to his frayed, experimental latter years. Was it a challenge to cover all aspects of his life and career?

DeNicola: Yes, and there was much debate about how much to cover – from gigging at CBGB’s in New York, to working with The Cramps, his tenure in Tav Falco’s Panther Burns, and on into his later years as the “human jukebox” –playing reinterpreting standards and recording numerous solo records. The guiding principle became an idea of seeing both Alex Chilton’s and Chris Bell’s lives after Big Star as constantly in the shadow of that brief time they spent recording together.

DeNicola: Yes, and there was much debate about how much to cover – from gigging at CBGB’s in New York, to working with The Cramps, his tenure in Tav Falco’s Panther Burns, and on into his later years as the “human jukebox” –playing reinterpreting standards and recording numerous solo records. The guiding principle became an idea of seeing both Alex Chilton’s and Chris Bell’s lives after Big Star as constantly in the shadow of that brief time they spent recording together.

For Chris Bell, the music became even more personal, and technically his method became a one-man studio band. The irony with Chilton is that he was always changing, always trying to move forward as the Big Star cult continued to grow. My story about being a disappointed Big Star fan watching Chilton shuck and jive his way through a rendition of the song “Volare” was a very familiar one for Big Star fans in the ’80s and ’90s, and I think that Chilton took some delight in this. He very much wanted to challenge the cult fans and open their minds a bit, and maybe piss them off too.

Filmmaker: How did you go about finding subjects to interview for the film? Were there people or perspectives that you were unable to get?

DeNicola: The beginning was Memphis, and the scene of kids that hung around Ardent Studios. It’s a story of everybody pitching in to try and make something happen. Chris Bell was the center of a very hip scene that started at his backhouse and moved over to Ardent Studios, which became the most sophisticated recording studio in the Mid-South in the early ’70s.

McCarthy: When I first started investigating whether or not I could make this film everyone told me I had to talk to John Fry at Ardent Studios (where the band recorded all three records). He’s basically the reason Big Star even existed essentially. He gave them keys to the studio, taught them how to record, bought them equipment, and landed them a record deal on top of engineering all their records. Fry was the key to it all – the “fifth” member of Big Star if you will. Fry still owns and operates Ardent Studios in Memphis He decided to come on board and has never wavered in his support for the film

We were trying to convince Alex to do an interview with us when he suddenly passed away in 2010. Of course that was very hard for us – to move forward without him – but luckily we gained access to some never-released audio interviews with Alex from Bruce Eaton’s book on Radio City. We’d love to interview Paul Westerberg, but I hear he doesn’t do interviews…much like Alex!

DeNicola: Which perspectives and how to treat them was a major creative concern. My feeling was always to keep a tension between two hemispheres: The little scene of people in Memphis, doing what Memphians do—make music—and “the rest of the world,” which by the time of Big Star’s first release was a highly corporate music machine. Woodstock had happened two years prior and rock and roll was now the dominant industry, over film and sports combined. A new band like Big Star coming out on a tiny label had no chance of breaking in at that time.

What emerges for us with that in terms of the narrative is a situation of fantasy and reality. The group had free reign at a world-class studio, they were on STAX Records, the little Memphis soul label that by 1971 was turning out multi-platinum records, and they garnered rave reviews when #1 Record was released. But they did not sell any records. They were completely dumbfounded. John Dando, Big Star’s road manager, said there was a sort of myopic view among the scene in Memphis that was in a way very powerful. A lot of the artists from Memphis are very uncompromising about their artistic integrity, and many have made their lives difficult in doing so. But that’s to be admired.

If commercial success is “reality,” then thank god Big Star held on to the fantasy. Their success came thirty years later, and it was a form of success that no amount of marketing could have ever have bought them. It’s almost as if they traded commercial success for a lasting legacy.

Filmmaker: Nothing Can Hurt Me is playing SXSW as a “work-in-progress.” How far are you from completing the project? What are your plans for the film once it’s complete?

Filmmaker: Nothing Can Hurt Me is playing SXSW as a “work-in-progress.” How far are you from completing the project? What are your plans for the film once it’s complete?

DeNicola: At this point we’ve taken a very good two-hour cut of the film down to an hour and a half. It’s functioning more as a highlights survey of the story of the band- from their inception to their demise and then to their eventual rediscovery. There are deeper themes about Chris Bell’s and Alex Chilton’s differing artistic trajectories after the failure of the Big Star project.

There’s also this quote from the author Robert Gordon: “Big Star is the epitome of Memphis obscurity.” We have followed that idea down a long and circuitous path that brings together Sam Phillips, William Eggleston and Jim Dickinson, and ends in a meditation on the state of music today. Big Star is a wonderful anomaly in this story. In the end we began to talk more about Big Star as a phenomenon than Big Star-as a band. The broader themes and interesting tangents are going to find their way back into the cut before we’re through.

We anticipate doing more interviews with musicians who were influenced by Big Star and hopefully will make it over to London where Chris Bell recorded (solo-album) I Am the Cosmos with Geoff Emerick (the Beatles’ engineer). The UK is also where the initial stirrings of a Big Star resurgence first took place, well into the 90’s when they were a sort of common denominator for much of the Brit-Pop scene during that time.

McCarthy: We hope to complete the film this summer and screen at some additional festivals. Then, if a solid distribution plan falls into place, we’d like to have the film available on iTunes or Amazon, and On Demand. We’d like to do a limited theatrical run followed by a deluxe DVD release, with an accompanying soundtrack and tons of bonus features. We want to satisfy the fans who’ve been waiting so patiently for us to finish the film, and we want to be able to get it out far and wide so everyone can finally see it! It’s been a long time coming.

Updated 3/16: Deleted an erroneous fact that stated Chilton was living in a tent in Memphis at the time of his death. Chilton had in actuality lived in a tent several years earlier, and was no longer doing so in 2010.