Back to selection

Back to selection

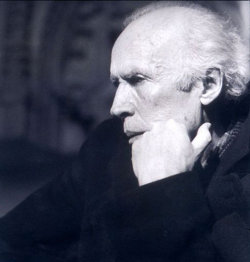

REMEMBERING ERIC ROHMER, 1920 – 2010

Eric Rohmer, the New Wave filmmaker who made intimate, conversational films exploring deep moral and ethical themes with a simple elegance, died today in Paris at the age of 89.

Like many of his colleagues in the French film movement, Rohmer began his career as a film critic, eventually becoming the editor of Cahiers du Cinema. Although he made his first feature in 1959, he became more widely known to international audiences in the late ’60s and ’70s, beginning with his Six Moral Tales, a series of six films which included his acclaimed My Night at Maude’s, Claire’s Knee, and Chloe in the Afternoon. Later films included Pauline at the Beach (part of his Comedies and Proverbs series) and A Winter’s Tale (part of his Tales of the Four Seasons). Later in life he moved from film to digital, making a period drama set during the French Revolution, The Lady and the Duke, on DV.

Rohmer’s films, with their long conversations, young characters, and emphases on moral dilemmas arising out of interpersonal drama, have always had a lot to say to American independent filmmakers. In 2001, on the occasion of a Stateside Rohmer retrospective, Peter Bowen wrote the following in Filmmaker:

ERIC ROHMER REMAINS one of the most revered and enigmatic directors to survive the French New Wave. His films rarely exhibit the revolutionary fervor so often associated with that cinematic movement. Indeed his chamber comedies of bourgeois desire and disappointment could easily be mistaken as nothing more than pretentious talk fests. But what keeps his feather-weight dramas and supercilious characters infinitely engaging is how their actions serve to illuminate complex philosophical and ethical dilemmas. In Rohmer’s films the focal points are never on what the characters say or do, but in the distance between those two, in that netherworld between language and action in which we all try to make sense of the world and of ourselves.

Peter went on to introduce three screenwriters — Ira Sachs, James Schamus and Larry Gross — who offered their take on Rohmer. Here is James Schamus’s:

Rohmer uses annoyance to achieve the sublime. His trick: to make us think that personality is a kind of illusory irritant, an encumbrance that keeps us from our presumed moral centers, but which, finally, turns out to be the very register of our moral being. Think of Delphine, the irrititatingly depressed secretary heroine of Le rayon vert (1986) — and one of the great mise en abymes of dialogue in cinema history: she’s at her friend’s summer cottage, an outsider surrounded by solicitous friends of friends, and she refuses the barbequed pork, politely explaining that she’s a vegetarian.

A polite query follows: “Should we prepare you something else?” “Sorry, we didn’t know of your specific dietary needs.” She tries her best to brush it off, but as she talks, and the more she talks, the more absurd, grating, hostile, self-defeating, alienating, tragic, weepy her explanations and excuses become. Rohmer creates an embarrassment so exquisite, a self-consciousness so finely attuned, this little scene takes on the psychic dimensions of a Busby Berkeley musical number, and all in glorious 16mm.

Click on the link to read Sachs’s and Gross’s appreciations of the filmmaker. And, below is the U.S. trailer for My Night at Maude’s plus a 1977 interview in which Rohmer discusses the talky nature of his films.