Back to selection

Back to selection

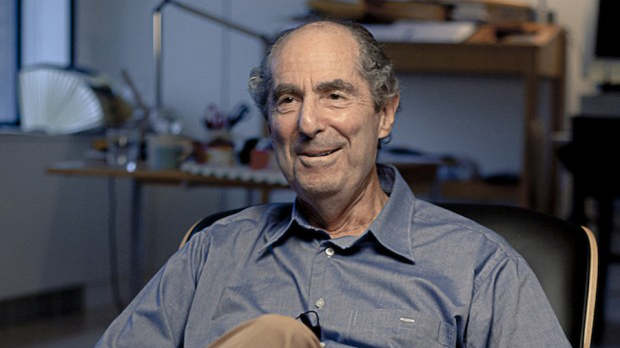

Five Questions with Philip Roth: Unmasked Director Livia Manera

Philip Roth: Unmasked

Philip Roth: Unmasked Livia Manera and William Karel don’t take many stylistic chances in their new documentary. But why would they? Granted extraordinary access to Philip Roth, one of the world’s greatest living writers and a man who’s never granted an abundance of interviews, the directors simply sat their subject in front of a camera and let him talk. Philip Roth: Unmasked finds the decorated author reflecting on every major development in his long career, from his prizewinning 1959 debut Goodbye, Columbus to the stardom that followed the publication of 1969’s Portnoy’s Complaint to the remarkably fruitful spell which has seen him publish a dozen novels since 1993.

Roth has won the Pulitzer, the National Book Award and most of the other major literary prizes, and the film duly celebrates his many achievements. But Unmasked is most fascinating when it demonstrates Roth’s day-to-day devotion to his work. Manera and Karel take us into Roth’s homes in Manhattan and rural Connecticut — we see him writing longhand, standing at the elevated desks he favors — and we learn fascinating tidbits about the intersection of his personal and professional lives. Though everyone who’s read Roth understands that his youth in Newark, N.J. has long been an important source of artistic inspiration, the film also chronicles how his friendship with Mia Farrow, who had polio as a child, seems to have informed the writing of Nemesis, Roth’s 2010 novel which dealt with the disease. Insights like these are particularly valuable given that Roth, who turns 80 this week, recently said that he’s done writing novels.

Philip Roth: Unmasked opens March 13 at Film Forum. On March 29 PBS will broadcast the film as part of its American Masters series. Manera, an Italian journalist and first-time director, took some time this week to answer a few questions.

Filmmaker: When did you first meet Roth, and how did you come to make the film?

Manera: I met him when The Human Stain was published in 2000. He gave one interview only in country, Italy, where I write for the leading national newspaper. We started a professional relationship, and it became a friendship. Later, I interviewed him four or five times for my newspaper over the years, more or less every time he published a new book.

I came to do the film in an oblique way. I was assigned a project of interviews with many American writers, and I was working on this project for Italian TV, Rai. I asked his advice about something that interested me, but I didn’t ask him to participate because I thought he wouldn’t do it. And instead he surprised me, more or less volunteering. So my project changed. I dropped the idea of doing a series on many writers and concentrated on Roth. We started with a 52-minute film, a co-production for Italian TV and Arte, the French-German cultural channel. Once we’d done that we contacted PBS and Susan Lacy of American Masters. She needed witnesses, more characters, so we added the writers Jonathan Franzen, Nathan Englander, Nicole Krauss and the critic Claudia Roth Pierpont [who appear in the film and speak about Roth’s work]. So the film became a new film.

Filmmaker: Is it true that you read or reread all of Roth’s novels before making the films?

Manera: I had read the most recent 10 books. But I decided I wanted to read everything from the beginning to the end. It was a very good decision — first of all personally, because it was a great adventure, to see the development of a writer throughout 60 years of work in a chronological way. Also, I found out that I didn’t realize how much he had written. He has written 31 books.

Filmmaker: Did you find that you became more familiar with his early work than he was at this point? Roth says that he hasn’t read his early novels in 40 years.

Manera: Of course, that would be true with any writer. We all think that they have in mind exactly all the details of what they’ve written, but writers move on. They usually don’t reread what they had written many years before — with some exceptions, of course.

When we interviewed him a second time he had just finished the process of reading his books backwards to The Counterlife [published in 1986]. He wanted to stop there because he thought those before The Counterlife didn’t count for him, they’re less important. He’d done it in order to collaborate with his biographer, who just moved into the picture.

Filmmaker: Was there anything off-limits?

Manera: He didn’t want to talk about his wives. [Roth married and divorced twice; his second wife was the actress Claire Bloom.] There is a little bit about the first one, but just because it explains why he sought psychoanalysis — psychoanalysis is important for [the plot of] Portnoy’s Complaint. But that was the only thing, really, that was off-limits.

Filmmaker: I was going to ask you why the film doesn’t mention his retirement, but just this afternoon I read an article in which you suggest he might change his mind. Is that right?

Manera: I knew that he wasn’t writing a book when we were shooting, but this was not official. So I didn’t reveal it. The press really made a fuss about this, and formed it into a declaration. But it was never meant to be, this I know for sure, from him. I think he gave up the obligation to write, the obligation he had with himself. In this sense it was a real decision, and it was a big decision, a decision that changed his life. But I’ll just ask you a question: Have you ever met a former writer in your life? A writer doesn’t become a former writer. This is for sure.