Back to selection

Back to selection

The Camera as Narrator: V/H/S/2

V/H/S/2

V/H/S/2 The new horror anthology film V/H/S/2–once you’ve shaken the blood from your hair–leaves behind some striking images and moments. Oh the lowly horror genre: the place where there is more cinematic risk-taking and experimentation happening than in the likes of “serious” films such as Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master or Terrence Malick’s pulseless To the Wonder. There is, in particular, one short sequence in V/H/S/2 where the experiments with camera narration are revealing not only in terms of the potential uses of narrative point of view but also in terms of how we process visual information.

It’s easier to think of books being narrated than films. While the usual narrative modes of literature–first, second, or third person with their various levels of omniscience–sometimes translate usefully to film, more often we only tend to think of film as “narrated” when narration itself is foregrounded, as in the voiceovers of Malik’s films. The film theorist David Bordwell’s ideas about narration in film are pretty well accepted. For Bordwell the totality of a film’s techniques, ranging from sound to editing, constitute the narration of a film. The “invisible” style of filmmaking perfected by Hollywood during its classic era meant that everything from style to sound to narration was sublimated to the larger project of storytelling. In this formula, a good movie (i.e., Casablanca) was one where viewers lost themselves in the world of the movie itself, getting carried away by the relentless push and pull of the story. Historically, detours from this formula that highlighted film technique–such as the auteurist films of Orson Welles or the stylizing lighting and framing of film noir–were the exceptions rather than the norm.

Of all the invisible parts that bring a film to life, perhaps narration is the hardest to detect. Leaving aside Bordwell’s notion that film narration is made up of all things that bring the story into being, how exactly do we locate the narrator of a film? There is the aforementioned voice-over. Or it could emanate from a central character whose world view and experiences we’re encouraged to identify with, such as Ree (Jennifer Lawrence) in Winter’s Bone (2010). But what of the camera itself, the seeing eye which renders all the visible experience in any film? Perhaps we tend to think of the camera as an object which constitutes point of view rather than narration because it is just that: an object, rather than a character is in a novel. And yet the camera–in all its embodied forms–is an object so intimately connected with us and how we see ourselves that it may be worth considering the camera itself as a narrator.

While the digital revolution associated with the Dogme 95 movement was not the first to liberate movie cameras from their dollys and tripods (many films ranging from Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929) to Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968) to those of the French New Wave to films like Haskell Wexler’s Medium Cool (1969) did that, pre-digitally) the smallness of the digital camera meant not only a fresh aesthetics, but a pronounced awareness of the camera as narrator. It’s not just the jerky movement of the camera that draws attention, but the fact of the camera itself as more than just the instrument that establishes point of view, but that narrates the film.

Perhaps because the horror genre is, at its heart, about the terror of seeing, it has in cinema become the richest genre for narrative experimentation. The Blair Witch Project (1999) deployed two first-person cameras with footage “edited” together after it was discovered, in something that roughly approximated, at a formal level, first-person narration. If Cloverfield (2008) exploited the full potential of the hand held first-person point of view, the Paranormal films–numbers 2 and 3 especially–experimented with the fixed camera as a third-person narrator: detached yet semi-omniscient. They are structuralist masterpieces, on par with Michael Snow’s Wavelength (1967).

Blair Witch toyed with an idea that hasn’t been used much since: dual-camera narrators. Shot on 16mm black-and-white film, and on a Hi-8mm consumer video camera bought from the retail store Circuit City, The Blair Witch Project itself acts as a splice between the analogue and digital eras. The alternating narrative points of view reach a climax at the end of the film, when the shifts between these two points of view become more frequent. We are presented not only with alternating takes of the same events, but with alternating technological renderings of those events, as Heather (using the 16mm camera) and Mike (using the video camera) search an abandoned house for Josh, whose screams they think they hear.

Which brings is to the sequence in V/H/S/2. It’s a simple moment, as the private investigators Larry (Lawrence Michael Levine) and Ayesha (Kelsy Abbott) break into a house at night searching for a missing student, filming themselves in the process. The camera, with a light attached to it, records their activities, as does a button cam on Larry’s shirt. The interesting moment happens when, after Larry climbs through the window, Ayesha passes the camera to him. At this instant the narrative switches: we see things briefly from his button cam point of view now. And then there is another narrative switch, as Larry sets the camera down to help Ayesha through the window, so that the sequence switches for the first time to the equivalent of third-person, until Larry picks the camera back up again. If we think of the camera as an extension of the person wielding it–it adopts that person’s general perspective and curiosity, and curiosity is really a function of thinking–then perhaps it’s not so far-fetched to imagine the camera itself as the narrator of any film, even films where the person operating the camera is invisible.

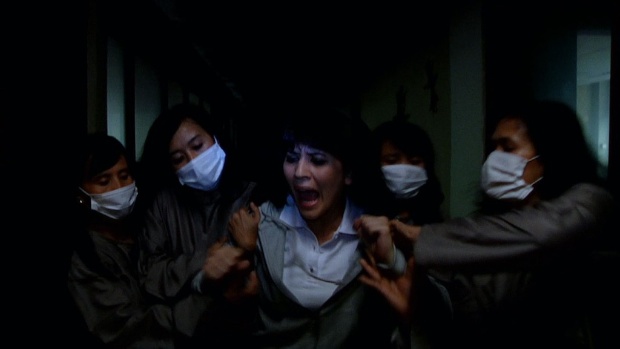

Here is the sequence:

Even though the shots unfold rapidly, as viewers we imaginatively construct the fullness of the space we’re only glimpsing. There is depicted space and implied space, in this case the rest of the house that we haven’t seen yet that extends beyond the room itself. The writer Jean-Pierre Oudart wrote about how films “suture” their audiences into their worlds. His ideas gained currency in the heady days of late-60s film theory, when he explored how movies worked, largely through editing, to invite the viewer to construct a sort of seamless, coherent space which does not really exist. Until the advent of the VCR and other home playback systems films–unlike novels–were not something that could be paused or bookmarked. In the theaters they mystified in a total, and potentially dangerous, sort of way, and that’s what Oudart and other radical film theorists hoped to resist through their intricate, unsentimental writings.

The power of the breaking-into-the-house sequence has everything to do with the ways in which information is released, in this case by toggling between four different narrative perspectives, a form of experimentation which is akin to the elaborate footnotes within footnotes in the fiction of Mark Danielewski, or the proliferation of screens we encounter daily. And as the wrap-around, frame story, this sequence embeds stories (in the form of the VHS tapes) which themselves contain their own experiments with point of view and narrative.

It’s as if today as we exert more and more power over images, which we relentlessly survey, manipulate, and dissect, we ask for something in return. What we ask for is to be surprised. To be mystified. To be cast under the spell of the old magic, the old illusions. The power of a film like V/H/S/2 is that it answers this call by embedding its mysteries not in the stories it tells, but the very mode of their telling.