Back to selection

Back to selection

#ArtistServices Austin Workshop: Talking Crowdfunding, Torrents, DCP and More

Crowdfunding panelists (L-R) attorney Deena Kalai, filmmaker Evan Glodell, Indiegogo's Shannon Swallow and tax adviser Cameron Keng via Skype. Photographer: Chale Nafus

Crowdfunding panelists (L-R) attorney Deena Kalai, filmmaker Evan Glodell, Indiegogo's Shannon Swallow and tax adviser Cameron Keng via Skype. Photographer: Chale Nafus Sundance often faces criticism from the independent film community as being inaccessible and too commercial. Two weekends ago Austin Studios, the Sundance Institute and the Austin Film Society held the sold-out “#ArtistServices Austin Workshop,” proving Robert Redford’s initial vision of supporting truly indie film is strongly intact.

The day-long event was focused on educating filmmakers about the business side of fundraising, marketing, and distribution for small movies. Filled with local filmmakers like Two Step director Alex Johnson and Before You Know It director PJ Raval and producer Annie Bush, the raw hanger space (Austin Studios is located on the site of the city’s former airport) was outfitted with banquet chairs and a stage. Also attending were festival programmers and distributors like SXSW’s Janet Pierson and Claudette Godfrey, newly appointed Creative Director of the Austin Film Festival Erin Halligan, and Brian Parsons of the DIY distribution outfit Tugg Inc.

Sundance Institute’s Director of Digital Initiatives, Joe Beyer, set an anti-authoritarian tone, infusing the day with a DIY spirit, encouraging openness, honesty, and access from the presenters and the audience. Panels would turn from presentation to open discussion and back again, with mics being passed around the engaged and informed crowd. The presenters encouraged audience members to contact them, and freely put their information up on the screen.

After an introduction by AFS Associate Artistic Director Holly Herrick, the day kicked off with a panel discussion about the business side of crowdfunding. This important topic, often an oversight for creatives, proved to be incredibly relevant to an audience where over three-quarters had been part of a crowdfunding campaign at some time. Lawyers Cameron Keng and Deena Kalai covered themselves, insisting they weren’t giving tax advice, but encouraged filmmakers to engage a CPA before starting a crowdfunding campaign. They stressed that Uncle Sam is very much interested in what happens to the income — and it is income, not a charitable donation — that comes in from these campaigns. What seems like free money in December quickly becomes taxable income in April if left unspent. Imagine raising over $100,000, only to have 40% of that taken in taxes, along with up to 9% in fees from the crowdfunding platform.

Hearing these horror stories, Evan Glodell — the DIY filmmaker known for setting the festival world ablaze with his debut, Bellflower — must have wanted to run off the panel and call his accountant. For Glodell, “Crowdfunding is the most important thing to happen to film in a long time. It’s like magic. I would definitely do it again.” His latest project, Chuck Hank and the San Diego Twins, was ignored by financiers until his team raised over $130,000 on Kickstarter, at which point they loosened their pockets. To these investors, what was once a risk is now a product with a proven market. Not only did it put more creative power in the filmmakers’ hands, it meant they had to give away less equity. This type of hybrid financing — also used by the Sundance Jury Prize winning, Dear White People — is rarely done now but will become more common in the future. Indies can consider this a tactic to use with potential investors, putting triggers in contracts that go off if they raise a certain percentage of their budget themselves. As outlined by IndieGoGo’s Head of Marketing Communications, Shannon Swallow, crowdfunding is now a four to five billion dollar industry and is not being ignored by industry leaders. The big secret is that distributors and foreign sales reps are now looking to crowdfunding campaigns for acquisition valuations.

During the most technical presentation of the day, producer Emily Eddey (from cutting-edge post-house Light Iron) and Graef Allen (manager of content services from Dolby) dived deep into the world of deliverables for indies. They mainly focused on DCP, a file-based format which is stored on hard drives rather than discs, tape, or film. While the “Digital Cinema Package” is relatively new, it has quickly become the standard screening format for both major releases and film festivals. Unheard of in the festival world only ten years ago, DCPs now account for over 75% of the movies at Sundance, eclipsing HDCAM, Blu-Ray, and film.

The biggest takeaway was a unilateral agreement from Sundance and SXSW reps, Eddey, and Allen for indies to steer clear of encryption for their festival DCPs. Since the complex encryption keys are linked not only to the theater but the individual projectors, one wrong number or a sudden change in venue can dismantle an entire screening, sending festival staff scrambling and filmmakers into a nervous breakdown. Another pitfall to avoid with DCP is relying on the embedded XML text file for subtitling a film. The new technology, which lets the DCP communicate with the projector, is constantly in flux, which means an update can change how the text is displayed. It was suggested that a version with burned-in subtitles be made, so the movie will be consistent no matter what. Eddey also stressed the importance of negotiating deliverable requirements with a distributor, as they may be using boilerplate deals that could cost the filmmaker thousands in unneeded tapes or a film out. Allen offered the cost-saving tip that productions can purchase their own drives and enclosures, and bring them to a post house themselves.

This led to a discussion about how DCP can help or hurt short-run theatrical engagements. On one hand, if they’re made with a CRU hard drive (a technology developed by the military), they’ll withstand the rigors of shipping from theater-to-theater, unlike a Blu-Ray, which can be easily scratched. But DCP screeners from a distributor can also come with a profit-eating “Virtual Print Fee,” which can be avoided by using Blu-Ray instead. With this advice, Joe Beyer proved that the Sundance Institute is keenly aware and supportive of ultra-low budget DIY distribution.

During an informal lunch of burgers and chips, the filmmakers, panelists, and festival programmers mingled freely and shared picnic tables. People casually reconnected or met for the first time, discussing anything from sound mixing or distribution, or — in the spirit of Austin weirdness — getting pulled over while on mushrooms after a festival premiere screening.

After lunch, David Larkin presented his company GoWatchIt. The problem? There’s a huge gap between content discovery and consumption. A potential viewer may hear of an awesome movie at Sundance, but then forget about it by the time it comes out. That makes a film festival premiere a launch pad for a product which no one can use. David is trying to change that. More than just an app and a website, his database driven software is already tied into huge websites like Buzzfeed, The New York Times, and RogerEbert.com. It’s also a part of Sundance’s online schedule, with many other festivals to come. As a user, you choose the platforms you watch movies on, and if you’re interested in a film, click the “Queue It” button that will be showing up more and more around the internet. Later, you’ll get updates when movies become available to watch. It’s similar to how Facebook’s “Like” button can be found all over the web, but Larkin says the data collected by GoWatchIt is much more valuable to studios and distributors. This year at Sundance, he received tens of thousands of queues from people who want updates about a movie they missed during the festival. With his software, it’s no longer on the customer to remember to see a movie. Now the information comes straight to them. At the same time, this creates a Netflix-like database on what a user likes, so others movies can be recommended to them. Unlike Facebook’s “Like” system, where updates only reach a low percentage of users at a time, GoWatchIt hits everyone who queued a movie.

This is all well and good for David and his partners, but how does it filter down to indie filmmakers? Partnerships with festivals mean that movies can start collecting queues before they’re even acquired. He has also partnered with indie distributors like FilmBuff, Gravitas, and Magnolia, who can use the collected data to help market the film. Filmmakers can include the GoWatchIt buttons on their website or even on Facebook. When the film comes out, everyone who Queued It gets an update. That means more people who wanted to see your movie will be reminded of it, with less of a marketing spend, and less reliance on press. I wish I would have heard of this before the premiere of our film, Congratulations.

Next up was a discussion about creating key art that works in a digital world. Gone are the days when movie posters lived only in front of the theater and in Blockbuster. Now they’re all over the internet, and can be used to create excitement for a premiere, even before teaser trailers come out. I remember my Facebook friends linking to a Slashfilm article about the poster for We Gotta Get Out of This Place, which premiered at TIFF in 2013. All of that great press, just over a poster! It got me excited to see it, so it worked. (Too bad I wasn’t using GoWatchIt, because I have no idea if that movie is out yet. Wait. It isn’t.)

When it comes to poster design, esoteric isn’t always better. Filmmaker/graphic designer Yen Tan (Pit Stop) and Mondo producer Rob Jones surprisingly came to the defense of studios and distributors, saying they’ve come a long way from the “floating heads” designs of the past. One example was a before and after for Escape from Tomorrowland, where the distributor improved the filmmaker’s complex design by going with a simple graphic image of Mickey’s clutched hand dripping in blood. Sometimes, the big face of a known actor on a thumbnail will lure a potential viewer to click, and clicks are more important than anything else. Even Yen Tan, who designed a beautiful graphic illustration for his festival poster, went with a more straightforward design of two shirtless guys spooning in bed for the release key art. He decided that was a better way to market the film directly to its intended audience, even if most of the film isn’t shirtless and spooning.

Both Tan and Melanie Miller, from indie distributor Gravitas, stressed the need for filmmakers to hire an on-set photographer. Spend the money. It’s worth it. Many posters are collaged together from these high-res stills. Too often, indie filmmakers ignore this advice, and try to cobble together a poster from screengrabs. Movies are shot in widescreen. Posters are vertical. These things don’t mix well. It’s worth the extra cash up front so a designer will have all of the resources they need to make a great poster.

After that, Sundance Institute’s Chris Horton took the stage with his former boss, Cinetic Media’s John Sloss, industry veteran producer and sales agent. Sloss embodied the DIY spirit of the event by embracing crowdfunding early, proving there was a punk-rocker somewhere under his lawyer exterior. He was candid and casual with Horton, making the segment feel more like a live podcast than an interview. He shared an old story about trying to get Kevin Smith to crowdfund Clerks III only to get rebuffed by the director, who didn’t want to come across as a beggar. Sloss is particularly excited about the community-building side of crowdfunding, which gives a film’s core fans exclusive access to the movie and in turn provides free word of mouth publicity. When the Cinetic-repped Roger Ebert doc Life Itself premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, it also streamed to around 1,500 screens around the world to those who chipped into the IndieGoGo campaign. Cinetic may have ruffled some distributors’ feathers, but they had enough industry clout to get away with it.

Sloss comes across as someone who wants to ruffle feathers, not doing something differently just for the hell of it, but because it’s a better way to reach an audience or market a film. Horton and Sloss went on to tell the story from the good old days of $10m+ acquisitions, when they left distributors salivating after an electric premiere screening of Little Miss Sunshine. They took off out a side door, only to get lost in the snowdrifts of a high school football field. When the only way to the car was over a fence, Horton made it over — but his hand didn’t, and he has the scar to prove it. They pushed on, ending up at a Denny’s outside of Park City, where they watched the phone ring off to hook, to build more and more hunger in the buyers. We all know how that story ends: never-ending pancakes and a $10 million sale to Fox Searchlight.

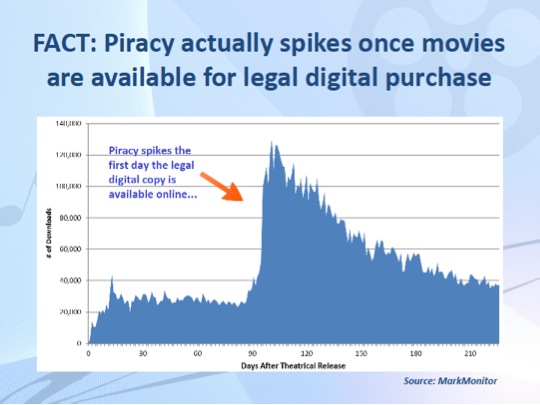

The event turned contentious when studio executive turned anti-piracy activist Ruth Vitale came out guns blazing against Drafthouse’s Tim League and BitTorrent’s Straith Schreder. She rallied against their laissez-faire attitudes towards piracy, insisting that it was hurting both studios and indies. She proved that the common argument that correlates lack of access to piracy just isn’t true. Her infographic (image below) showed that piracy spikes three-fold once a film is released on legal digital platforms. League was somewhat unfairly linked with piracy, since he used torrents as a way to release supplementary materials for the Drafthouse Films doc The Act of Killing. Leveraging a technology for promotional purposes is not the same as being a pirate, and standing behind a file format and delivery system doesn’t either. Vitale could have easily recruited League onto her side of the debate if she hadn’t sucker punched him before the bell rang.

There is nothing inherently wrong with torrents, it’s what the piracy community does with the technology. Schreder chose to hide behind that argument a bit too much, unable to come up with a proper defense against Vitale, stumbling into a buzzword-laden explanation where little was actually said. She insisted that BitTorrent has “pay-gate” technology coming soon, which could turn would-be pirates into paying customers. But if it’s not about access, then these pay-gates will just be yet another way to legally download, and pirates will find another way to steal. It’ll mean profits for BitTorrent but doesn’t address the core issue. Ultimately, it’s not BitTorrent’s responsibility to stop piracy, so it’s hard to expect much more than a shoulder shrug from a company built on an ethos of sharing and openness.

Vitale connected with the audience when she brought up that foreign sales, especially in Spain, have dried up as a result of piracy. This lynchpin of independent financing and distribution could wither away unless piracy can be abated. CreativeFuture has made that their mission, partnering with studios, advertisers, agencies, and more to get profits away from the Russian mafia and back into distributor pockets where they belong. If someone’s going to screw over a filmmaker, they might as well have a contract acknowledging it.

David Larkin spoke up from the audience to say that many pirate sites don’t even link to working torrents. They’re just doing better SEO campaigns than studios, claiming the number one search engine spot, and luring potential pirates to their ads, which are sometimes ironically paid for by the studios themselves. Vitale responded by saying that the industry is aware of this, and is working on better accountability for ad-buying.

Joe Beyer wrapped up the day with a funny list of Tweetable takeaways from the event. Afterward, panelists and the audience were invited to a happy hour in another part of the studio. They continued the lively conversation, swapping business cards, and sweating in the Austin heat.

Eric M. Levy is a writer and director living in Los Angeles. He co-directed the indie feature, Congratulations, starring Brian Dietzen (NCIS), Abby Miller (Justified) and Debra Jo Rupp (That 70’s Show). It premiered at the Austin Film Festival in 2012, and is now available through FilmBuff, and you can watch it now on most platforms. His new project, co-written with Juan Cardarelli, is an adaptation of Cecil Castellucci’s young adult sci-fi novel, First Day on Earth. They are repped by George Heller at Apostle and Mike Esola at WME. Additionally, their company Render Guys provides visual effects and motion graphics for features, commercials, and documentaries.