Back to selection

Back to selection

Mad Men: The NYFF’s Go-To Films (II)

Tales of the Grim Sleeper

Tales of the Grim Sleeper Can we permanently delete the term “home stretch” in a festival context? All right then. In the NYFF’s final week, the best fiction in the Main Slate is stronger (arguably) and more obscure (undoubtedly) than just about everything that has come before. Products of exceptional minds creating in different keys, these three gems (Horse Money, Jauja, Life of Riley) do share some elements that could make them off-putting for the passive viewer. All bets are off for anyone looking for the expected visual and aural cues. Each of these directors builds a self-contained universe with its own rules of engagement. None is a slave to seamless classic filmmaking; each embraces the un-real. Artifice reigns. Sticking Alain Resnais in bed with Lisandro Alonso and Pedro Costa just frissons me up.

Of the must-see titles below, the doc-to-fiction ratio is one-to-one — amazing considering that, of the two docs in the Main Slate, Laura Poitras’s eagerly anticipated CITIZENFOUR is not yet available for preview. Cherry picking from the Spotlight on Documentary, I found two (Merchants of Doubt, Red Army) that, like Nick Broomfield’s Tales of the Grim Sleeper in the Main Slate, are no less accomplished and provocative than the fiction. Hail realism.

Nothing is so cut and dry, of course. Grim Sleeper, for example, falls into a gap. Its overall style is, like many docs, naturalistic, but the filmmaker exposes the process, giving the film a self-reflexive tinge found in the fiction. Broomfield was putting himself into his docs long before Moore, Spurlock et al marketed the strategy, and once again he holds on tight to that big boom. Am I giving undue credit, or did the programmers intentionally, and brilliantly, schedule Grim Sleeper to coincide with those features?

The first two titles below share highest approval rating; those that follow are listed in preferential order.

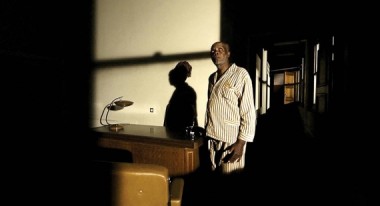

Horse Money (Pedro Costa, Portugal), MAIN SLATE

Ventura, the formidable black immigrant from Cape Verde whom Costa first introduced in 2006’s Colossal Youth, reappears as a gray-bearded shell of the bricklayer and revolutionary he once was, navigating the forbidding, squid-inky corridors of a mental asylum in striped pajamas at an unhurried pace, not unlike that at which the film itself moves. Suffering from dementia and a nervous condition that causes his hands to tremble, he passes through spaces defined more by extremes of light and shadow than walls and ceilings, settings that could be out of Costa’s beloved Val Lewton horror movies, but firmly rooted in their forebears, German Expressionist films, with Ventura’s resemblance to the sleepwalking Cesare in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari adding to the sense of warped time in a deranged psyche. Everything is in the present tense.

Just about the entire film is comprised of interiors, three-dimensional projections of the site Costa is actually exploring: the inside of his mind. Given the constraints of an interior shoot, he teases with his unusual, often oblique frames-within-the-frame and the ways they can suddenly, blindingly flood a shot with light.

Along the way Ventura encounters people, imagined or real; the latter, clearly in no logical order. Their dramatic weight varies only in relation to his perception and what remains of his memory. The most powerful presence is Vitalina Varela, a woman whose relationship to Ventura is unclear. We see and hear her, always in a whisper, recount elements of his past and her own, including such seeming banalities as the details of her birth certificate, which are in fact of huge significance to impoverished immigrants. He sees, one after the other, friends and neighbors he knew in the now-demolished Lisbon neighborhood of Fontainhas, men from the lowest rungs of society, echoes of a montage of striking Jacob Riis photographs of New York City slum dwellers during a prolonged silence at the beginning of the film. Ventura registers, Costa ennobles.

He begins to relive other early experiences: working as a teen in a factory, fighting fascists. The film warms up whenever the men break into song, the lyrics owning up to the hardships of their day-to-day lives, but the soulful melodies joyful. He speaks about the knife fight he had with his friend Joaquim during the 1975 Carnation Revolution and its lasting effects. The disjointed recollections lead toward a lengthy but stirring dialogue with himself in an elevator, witnessed by an enlarged toy soldier in changing positions painted to look like a partner in combat. I won’t ruin the ending; let’s just say that it is startling and heavy however you choose to interpret it.

Jauja (Lisandro Alonso, Argentina/Denmark/France/Mexico), MAIN SLATE

Lead actor and co-producer Viggo Mortensen calls Alonso’s creative process “distillation.” In this quasi-period piece, set in 1882 in the southern pampas of Argentina, the filmmaker arranges sharp, concise images in a deceptively simple way, without unnecessary embellishment, though he manages to deliver a narrative that has complex psychological, metaphysical, existential, and political implications (imperialism, anyone?). The film makes two jarring detours that have knocked some smug reviewers off their lofty perches, yet these are earned, accessible and, as far as I’m concerned, monotony-relieving. (That is, if, you find sameness in Finnish DP Timo Salminen’s gorgeously composed shots of a lone, crazily determined man traipsing through subtle variations of nature, on foot and on horse, through desert, tall grass and swamp.)

Mortensen portrays Danish Captain Gunnar Dinesen — the film’s two languages are Danish and Spanish — who has taken a job as an engineer with the Argentinian army during what was called the “Conquest of the Desert,” a euphemism for the extermination of the indigenous people. A single, overly possessive father who, though incompetent as a military man, keeps his uniform just-so, he has brought his 15-year-old red-haired daughter, Inge (Villbjork Mallin Agger), who becomes an instant sex magnet for the bestial, horny soldiers he is accompanying. On to the situation while camped at a delicious rocky coastal site, he has to refocus his anxiety once she runs off with a dashing young member of the unit. Behaving more like a stud following the scent of a bitch than a father tracking down his child, he chases the couple through enemy territory, acting out his Oedipal frustration by symbolically castrating the severely wounded boyfriend with a swift decapitation courtesy of his long sharp sword.

Heartbroken, Dinesen begins to lose his sanity. He continues the search. There is no logical explanation for his discovery of a lair in which resides not an animal but an old woman (Danish legend Ghita Norby). Let’s just say she turns out to be Woman, full stop. Following this revealing encounter, Alonso (Los Muertos, Liverpool) takes us on another trip that also defies reason. A movie that had begun by focusing on mere carnality — hell, the Argentinian captain was jerking off in plain sight of the girl’s daddy — shifts gears with a cut and dares pierce other dimensions. Alonso has chutzpah in spades: he brings to life an updated Twilight Zone-like effect inside a square with rounded corners, very silent cinema, as antiquated a shape as you could come up with. A multitasking genius, he ruptures time both inside and outside the frame.

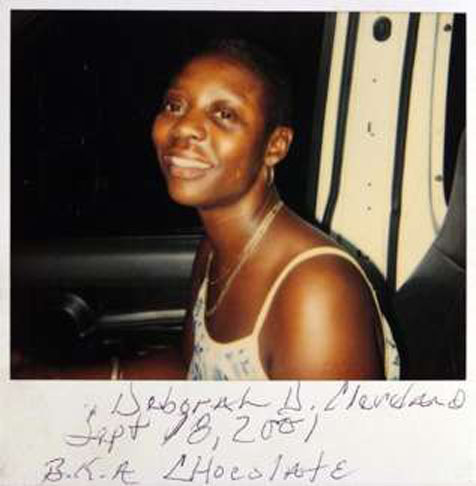

Tales of the Grim Sleeper (Nick Broomfield, US/UK), MAIN SLATE

Docmaker Broomfield (Kurt & Courtney, Battle for Haditha) is partial but democratic. He made two films about Aileen Wournos, a white lesbian prostitute, abused as a child, who hated men and killed seven. In those films he touched on the media’s response and her treatment in prison. Now, he has made a documentary about Lonnie Franklin Jr., a black man who despised women, especially crack addicts (his friends attribute it to lingering contempt for a first wife who spent money on drugs), and between 1988 and 2010 tortured and murdered perhaps more than 100, nearly all prostitutes and/or crack addicts, deluding himself that he was cleaning up the neighborhood.

He goes into South Central Los Angeles looking for sources to expose the Los Angeles Police Department, who swept the mounting cases under the rug by classifying them “NHI” (i.e., “No Humans Involved”); the city of Los Angeles, for not warning the public for 22 years about a murder spree in poor, crime-and-drug-ridden South Central Los Angles for which there was more than ample evidence; and, as the film goes on, a social order — ours — in which human beings are stripped of their basic dignity and right to live.

Incredibly, many in the community did not know about the serial killer. One woman remarks that this could only happen in a black or brown community. “We have no lobbyists,” says another. One activist notes that if just one young female disappeared in Beverly Hills, the police and media would be all over it. During all these years, while the killer was inviting addicts into his van for photos for his home collection (see image at top), only a few brave, vocal women from the neighborhood, who called themselves the Black Coalition Fighting Back Serial Murders, worked to warn the vulnerable and force the cops and city into action.

They were unable to contain their frustration. When the mayor and chief of police, with Governor Brown in attendance, held a self-serving press conference following Franklin’s arrest in 2010, the coalition’s outspoken Margaret Prescod snatched the mike from the speechless mayor to set the record straight. Later she tells Broomfield, “They said they wanted a big show!” She holds her own press conference the following day. Not surprisingly, all of the authorities declined to speak to Broomfield.

A major obstacle to finding the culprit was the survivors’ fear that their addictions would be held against them, not to mention the phobia of police embedded in everyone in the neighborhood. Just getting information for a sketch artist was a major undertaking. Pam Brook, a former prostitute with the flamboyance and gall of a no-holds-barred stage comic (she receives a credit as “South Central Guide and Coordinator”), introduces Broomfield to several helpful women along the way, but her greatest contribution is assembling the hidden victims who had dared not speak out for a shocking, tearful climax that few will forget.

Along the way, Broomfield meets Franklin’s best friends, first as a trio, then separately when they provide useful information; a homeless man who earned money cleaning out the back of the van post-coital; and, after many attempts, his loyal son, Chris, whose DNA from a cup in a pizza franchise provided the evidence linking his dad to the murders. We learn a lot about the elder Franklin, a garbage-truck driver liked by his neighbors: He kept a messy house, owned a lot of porn, lived separately from his church-going wife, did not keep his sadistic tendencies toward women a secret from his buddies. Ultimately, he proves to be less than interesting, and because they are so numerous, the dead young women end up being numbers. The real star of the show is the community, warts and all, and how it is perceived outside.

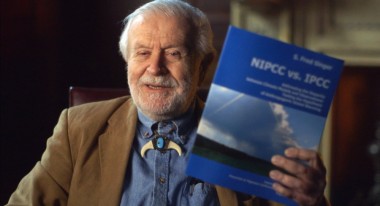

Merchants of Doubt (Robert Kenner, US), SPOTLIGHT ON DOCUMENTARY

How depressing that a few spinmeisters — publicists, lobbyists, scientists-for-hire (Fred Singer and Fred Seitz, over and over) — or ideological hacks can muster up enough successive controversies about a scientifically-proven issues to result in the postponement or the abandonment of legislation that serves us all — all but the corporations that benefit financially from the status quo, no matter how damaging. Kenner (Food, Inc.) clarifies just how organized these forces of opposition are, and how the same naysayers drift from panel to panel, hearing to hearing, Fox News program to Fox News program, challenging the scientific consensus on global warming, tobacco, and fire retardants, just for starters.

“Inspired by” the book of the same title by Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway, the film dwells on some truisms but, in the context of issues discussed here, they aid in unraveling the methodology of these tricksters and their well-financed backers. Oreskes herself says that scientists are not particularly telegenic or media savvy, something the tobacco industry understood soon after the harmful effects of smoking were made public when they hired the high-powered PR firm Hill & Knowlton to contradict the facts. On Fox News you get an expert in physics or chemistry on one side of the screen; on the other. a smooth operator like the infamous Marc Marano, a disciple of Rush Limbaugh who specializes in little but spin. He proudly tells Kenner about his role in “creating chaos” and “casting doubt,” shamelessly naming character assassination and the encouragement of threatening e-mails among his tactics.

The ideologues hide their true intentions behind misleading monikers that sound progressive about climate change (Science and Environmental Policy Project) or wildlife endangerment, for example. The Koch Brothers and their political organization, Americans for Prosperity, are strong backers of vague refutation of any progress on, say, climate change: Curbing pollution and carbon dioxide emissions in particular would cut into their huge profits. They garner acolytes with such loaded terminology as “government interference” and “freedom of the individual.” They are all about anti-regulation of anything.

Republicans, of course, tend to respond to this train of thought. A flicker of hope appears in the form of former Congressman Bob Inglis, Republican of South Carolina, a rabid conservative who saw for himself in the Arctic a thick core of ice he could not argue with. He returned home, broke rank, and lost heavily in the next election, yet he fights to educate people about global warming. He thinks that a lot of people resist accepting human responsibility for climate change because it would necessitate changes in the way we live that we do not want to face. Then there is Matthew Crawford, a motorcycle shop repairman who had quit his lofty job as executive director of a conservative think tank that fought the idea of a human component to climate change when he discovered that an oil company was funding the organization.

Kenner interweaves a stylistic theme of magic and deception throughout. A magician, Jamy Ian Swiss, performs tricks and speaks about the difference between his “honest<" lies and those of the greedy manipulators; on the soundtrack are some fine if a bit obvious standards like "That Old Black Magic." The assemblage is slick, engaging. There is always a risk in jazzing some things up when the talking heads and other footage remind you of what Oreskes notes about scientists. Whatever. Watching this thorough doc about how the system works, apparently to our disadvantage, is a must.

[caption id="attachment_87810" align="aligncenter" width="380"] Red Army: Slava Fetisov, Viktor Tikhonov

Red Army: Slava Fetisov, Viktor Tikhonov

Courtesy Polsky Films[/caption]

Red Army (Gabe Polsky, US), SPOTLIGHT ON DOCUMENTARY

Hockey in the former Soviet Union was played very differently from the roughhouse game we are used to in North America. A sport that was as important to the image of the government in the ‘70s and ‘80s as cinema was in post-revolutionary times, hockey was treated as much as an art form as a sport. The legendary Anatoli Tarasov, the first teacher of the CSKA Moscow Red Army team (it was part of the military), analyzed ballet and chess for methods he could appropriate. It’s not surprising that the squad played gracefully, and, given the society they lived in, collectively.

Joining the NHL during Perestroika was one of many detours taken during his illustrious career by Slava Fetisov, the principal subject of the film. A defender on the team, he suffered dearly for standing up for himself — by demanding a good percentage of his earnings — when he was offered a contract by the Americans. But when he finally won the battle, he did not easily adjust to the new style. As a result, the players disliked him; even their wives shunned his. (Some of the media were hysterical about the red playing in the U.S.) It would be an ill fit until the Detroit Redwings recreated the former so-called “Dream Team” by inviting his former mates to join him.

Polsky did his homework, culling through archival footage for impressive material from the height of the success of what was officially called the “Green Unit,” as well as their participation in the devastating Winter Olympics in Lake Placid in 1980 (they lost to the US) and Fetisov’s personal success in Sarajevo in 1984 (he won gold). He cuts back and forth between a long interview in that subject’s luxe Russian home and clips from his professional life. There’s not much from Fetisov’s personal one, except for an interview with his wife, Lada, unless it involved close friendships or squabbles with Red Army teammates, with whom he spent almost all of his time, especially after Tarasov was fired and the uncompromising bureaucratic disciplinarian Viktor Tikhonov came on board. Now that is a marriage definitely not made in heaven: You can see from the interview that the aloof Fetisov, frequently distracted by his iPhone, is not easy to deal with in the first place.

The man has led a life of very high ups and extremely low downs. A child of poverty, he was like a rock star in the USSR in the ‘70s and ‘80s, but was shunned after his first request to play in the States was turned down. After playing in the U.S., he reinvented himself as a coach, then returned to the country that was now called Russia. Rising like a phoenix from the ugly past in Moscow, he became Putin’s Minister of Sport for six years.

Through all of these shifts, Polsky wisely keeps tabs on his former teammates in the Green Unit, especially Alexei Kasatonov: BFF, then traitor, finally colleague in the ministry. He also interviews the former KGB agent who traveled with the team to the U.S. in their heyday, gauging his cool response to the country against Fetisov and the other young athletes’ wide-eyed embrace. It’s ironic how a similar first encounter with materialism turned the player’s stomach on his initial visit back to the newly capitalist Moscow after the collapse of the USSR.

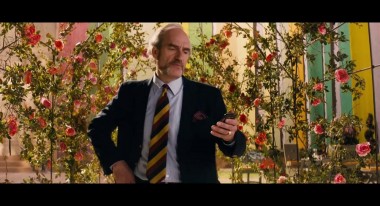

Life of Riley (Alain Resnais, France), MAIN SLATE

The only three-dimensional items in this satisfying cream puff (the original French title is Aimer, boire et chanter) are the six middle-aged characters, but even they spend much of their screen time practicing their roles in an amateur community production of Brit Alan Ayckbourn’s 1969 Relatively Speaking. Director Resnais makes it difficult to say they are not really themselves, because after a while the parts become similar to the characters performing them. We could say they are simulacrums of themselves, perhaps. To be sure, they intentionally overact most of the time, as if playing in the theater. Cinematographer Dominique Bouilleret shoots them in widescreen, fluidly moving in and out of their scenes.

Almost everything else in the film is theatrical. Backdrops are painted, shrubs are cardboard. For a close-up, Resnais cuts to an actor against a white backdrop with skinny black lines in the style of comic books, designed by the French illustrator Blutch — a distancing device with more punch than the stagey set-ups. To retain the Britishness of the source play, however, Resnais cuts to naturalistic tracking shots through the northeastern English countryside, where it is set. Returning to the French theatrical scenes kicks off the alienation process all over again.

Riley is the surname of George, a man who has been diagnosed with six months to live by his doctor friend Colin (Hippolyte Girardot), who sloppily tells his gossipy wife Catherine (Sabine Azema). She in turn relays the information to Jack (Michel Vuillermoz, a man of hilarious facial expressions), George’s oldest friend, who repeats it to his spouse, Tamara (Caroline Silhol, marvelous). When they aren’t talking about George’s imminent demise or how to convince him to participate in the play, they head off in different pursuits: Jack to his mistress, the two wives to compete for a last fling with the soon-to-depart. George — whom we never see — has, in the meantime, stirred up the waters, letting it be known that, in his weakened state, he requires a female companion to accompany him for a final journey to Tenerife.

One more couple rounds things out: Monica, George’s ex-wife (Sandrine Kiberlain), and her gentleman farmer, Simeon (Andre Dussolier). She expects the poor chap to wait in the wings while she comforts George during his final weeks. Of course she wants to go to the Canaries as well. It’s fun to watch the three women act out, especially with them all chewing up the scenery as if their careers depended on it. They have a big surprise in store. All the fuss is a worthy epitaph for George; the film itself, for Resnais.