Back to selection

Back to selection

How to Stretch One Apartment into Five Locations: Ricky D’Ambrose on Making Six Cents in the Pocket

Six Cents in the Pocket

Six Cents in the Pocket Ricky D’Ambrose’s Six Cents in the Pocket premiered at this year’s New York Film Festival. In a guest post, he explains how the film was made, in both technical and artistic terms.

Six Cents in the Pocket was made improbably, at a pittance, with a cast of four and a crew of two, for eight days in February and March of 2015. Shot chiefly in one apartment serving at different times as two separate homes, a coffee house, antique store, and a picture-frame shop, the film was a chance to satisfy, in some small way, two needs: first, to make something — anything — at no cost, with my own camera and in my own apartment, without a proper crew to speak of, and therefore as a rebuke to the long, disabling wait to finance a parallel film project that had, at that point, been in development for thirteen months; and second, to use up some of the things I’d been carrying with me as a viewer — specifically, and maybe most superficially, of Bresson, but also of Michael Snow, Straub-Huillet, Fassbinder, and of Peter Emanuel Goldman’s Echoes of Silence, a wordless, wandering nocturnal movie from 1967 set to Mingus and Stravinsky.

What follows are a few notes that, I hope, will be useful to other filmmakers working under (and against) similar prohibitions, and in advance of similar needs.

Practicals/impracticables

Six Cents in the Pocket used one Canon 60D — almost always with Technicolor’s CineStyle picture profile — and an EF-S 18–55mm lens, also by Canon. For monitoring, I relied on a detachable magnifying viewfinder by Zacuto, as the camera’s LCD is impracticable on its own for any kind of careful blocking and framing. An on-screen grid set the geometry of each shot, allowing verticals and horizontals to be leveled as accurately as possible — something relevant to this film’s flat, tidy treatment of tabletops, doorways, storefronts, and city streets.

Faces and flowers

An artificial light was used once, for a brief, daytime tea-drinking sequence between Clyde (Michael Wetherbee) and Ananda (Poppy Gordon) which, in order to shorten the depth between faces and flowers, benefitted from the diffuse, steady light of a 65-watt incandescent bulb inside a white paper lantern. (Most of the film, it should be added, was shot wide open, at f/3.5, and at 1/50 shutter speed.)

A score of sorts

The music came early, through casual listening and re-listening, and as a result of wanting to organize a film — to supplement its visual repetitiveness, to give it a sturdy sound repertoire — with five or six pieces, often sharply juxtaposed by cuts. (For instance, each of Clyde’s visits to the picture-frame shop consists of two consecutive shots, separated, we can assume, by a ten- or fifteen-minute gap. And we’re able to assume this chronological jump since the cut interrupts not only two separate images — Clyde taking the shop-owner’s invoice, Clyde paying in cash — but two separate helpings of incidental music, coming from a stereo someplace off-screen.)

None of Clyde’s footsteps were audio-recorded during the shoot: a sound library supplied the necessary shuffling and clacking of shoe soles. One exception is the film’s earliest noise — “a few dozen pairs of footsteps,” as the script puts it — which I recorded with an iPhone on the Sixteenth Street staircase of the Union Square subway station in New York.

For the voice-over narration, spoken by Caroline Luft, a Sennheiser shotgun microphone was connected to a digital audio recorder, while the film’s single instance of synchronous dialogue — for statements, spoken haltingly by Risa’s sister (Tallie Medel) — was captured with a Rode NTG3 microphone by filmmaker and sound-recordist Sean Dunn. All sound was edited and mixed by me in Final Cut Pro.

Organizing principles

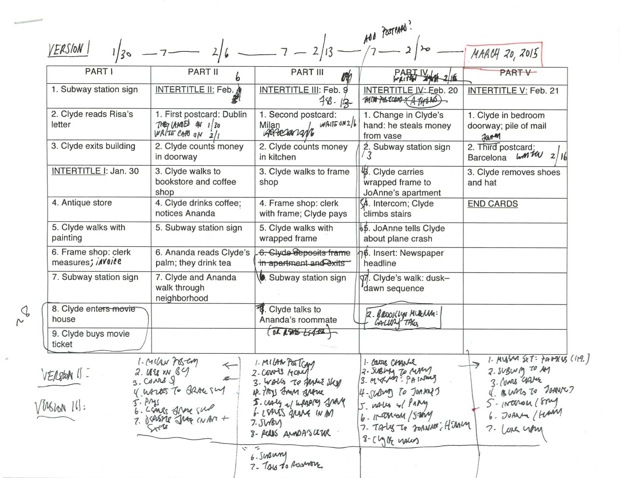

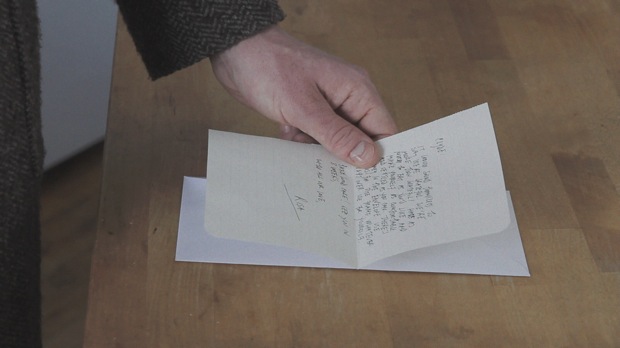

Some of the earliest preparatory notes I have for Six Cents in the Pocket include a casual list of images and sounds, or “key elements,” that would be set down and rearranged continuously before, during, and after the filming. (From my list: “room with floral wallpaper,” “V.O. narration progressively diminished by sound of city traffic,” “inserts of newspaper headlines,” “Riegger’s Wind Quintet — cuts timed to beats in composition — change in background color.”) Much of this list was later included in a series of five-column charts, drawn up as a way of collating and making sense of the material, structuring it, and giving the film a set of defined movements, through which its lead character could pass. Four scripts were written to reflect the contents of these charts, although only one version was distributed to the actors, and changes would continue to be made up until the start of post-production, at the end of March.

Withdrawn, unintentionally

Clyde’s long, concluding dusk-to-dawn walk was never intended to be implied: Clyde, or so I hoped, would be seen on screen for however many minutes were necessary. But the sequence’s innumerable street corners and sidewalks— a visual walking-tour of northern and central Brooklyn, beginning in Brooklyn Heights, moving to Williamsburg and Greenpoint, then to Dumbo, and ending in Prospect Heights — made this impossible. But filmmaking by implication is more satisfying, and ultimately more interesting, than any number of more explicit and intentional expository conceits can ever permit. It is also more difficult, done well, and less consoling, since the aim is to empty out the frame, one by one, until a few bare and winded stray parts are left in place.