Back to selection

Back to selection

Time Travel via Production Design: Jia Zhangke’s Mountains May Depart

Mountains May Depart

Mountains May Depart Mountains May Depart begins as a love triangle, whose three connecting lines separate and recross across three segments in 1999 (two years after Jia Zhangke’s debut feature), 2014 and 2025. The 1999 opening brings us back to Jia’s native Shanxi, whose streets by now look very, very familiar to anyone who’s kept up with his work. As Tao, the woman at the center of the love triangle, Jia’s professional/personal partner Zhao Tao is introduced in period peasant style: strategically layered brightly lined sweaters, nothing too form-fitting or fashion-forward, hair straight and uncomplicatedly pulled-back. In 2014 — following marriage and divorce to wealthy Zhang Jinsheng (Yi Zhang) — she’s visibly wealthier, wearing Western-style dresses and with some time-consumingly teased-out hair.

During this second sequence that I realized that periodizing his cinematic past in the movie’s first third is, effectively, Jia’s best option for returning to once-familiar terrain. 2006’s narrative Still Life incorporated real, startling footage of the demolition of entire villages to make way for the Three Gorges Dam. The stretch from that up to I Wish I Knew mingled both fact/fiction and timelines, looking backward and forward simultaneously. The generational gaps represented are huge: the testimony and experiences of older citizens forged under strict ideological control mingle with younger voices prospering under capitalistic expansion and those who haven’t made the great economic leap forward. Jia’s been documenting change in China for so long that when characters walk over bridges I’m unable to look at water without seeing the demolition that preceded it. I have no idea if I’m looking at the Three Gorges or natural bodies of water, but the connotation stands (especially because a regular recurring motif is explosives detonating in water).

As Jia’s said in interviews, he’s primarily interested in Mountains May Depart‘s obvious themes: how generational gaps become communication problems in families experiencing change and relocation, the net positive and negatives of capitalism on the new generation. What’s more interesting to me are his production design choices. There’s such a thing as piling on too many obvious period signifiers to unconvincingly simulate an era, but in the time and place Mountains begins there are very few new objects to notice. Two stand out: the Radio Shack-ish store Tao’s father runs, which comes stocked with cell phones and stereos (with three CD decks, two cassette slots, et al.). We know Zhang is wealthy because he shows up with a car – a boxy, clearly used vehicle that no one in the west would drive for style. (I think it’s an Audi, but I’m not sure.) “It’s German technology,” Zhang brags, but the car’s aesthetically nothing to write home about — true luxury goods aren’t on the market yet.

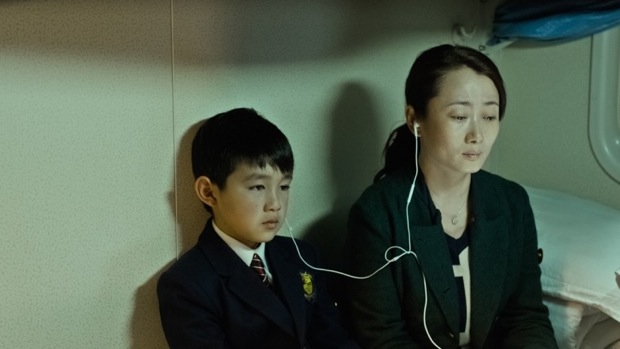

In 2014, Tao drives a shiny new Audi whose moneyed qualities come across a lot more clearly. When her son Dollar (yes, really and unfortunately) visits, she scrolls through his iPad and sees photos of luxury life in Shanghai, including one of him posing in hip-hop wear in front of a Maybach — a new materialization of luxury literally unenvisionable in China 20 years ago. No wonder Tao (who’s prospered and jumped several classes, but who still makes her own dumplings), chooses to take the trip to return Dollar to his father on an old, green-skin train: the connotational charge of soon-to-be-obsolete objects can’t be underestimated. (Small detail: when she gets to spend time with her son and worry about how disconnected he is from both her and his culture, her hair returns back to its 1999 look.)

Mountains May Depart is a steadily deflating mess, and (as widely noted) Jia does himself no favors by filming the last third in English. But I found it moving precisely because watching it reminded me that I’ve been watching his work for over a decade. I don’t get the majority of my news from movies, but they do provide a good starting point when deciding what to read up on, and Jia’s films have been consistently illuminating about what change in China looks like. Watching him crawl through his own past up to the present and beyond feels like the logical synopsis of everything he’s worked up to now. I can’t imagine watching this as an introduction; whatever impact it had for me was rooted in the cumulative wallop of remembering all Jia’s recorded that’s now gone.