Back to selection

Back to selection

True Crit

Weekly film reviews. by Howard Feinstein

Sex Ed: Stephanie Rothman’s The Student Nurses

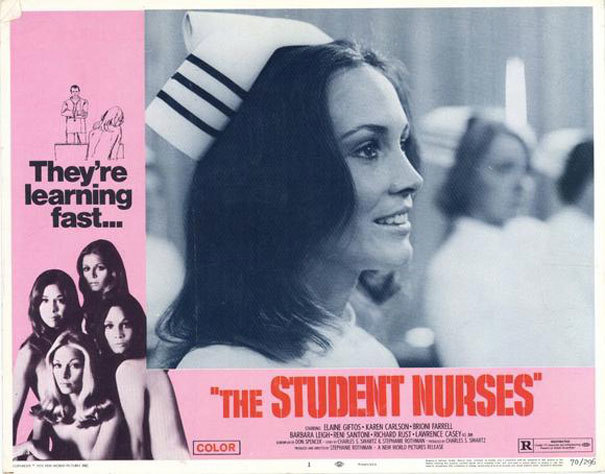

Barbara Leigh in The Student Nurses

Barbara Leigh in The Student Nurses During a moment of high drama in the very special cult item The Student Nurses, which runs in a restored version at the new Metrograph in New York’s Lower East Side for one week beginning March 11, a pretty young woman rudely dumps her frustrated doctor boyfriend in plain sight of the sexy roommates she trains with at a large LA hospital. On his way out, just before wishing a corny “Peace!” to the other vixens, who are seated side by side on the living room couch, he keeps the scene from wandering into the expected emotional terrain by lamenting to his now-former girlfriend, “Screwing was perfect with you.” Was the set-up designed to evoke chuckles? Or was it done in a more serious vein, but reads as funny 45 years on — qualifying it as camp?

Not long before, following a quickie with one of the poor sap’s fellow physicians from the same hospital, she had told him firmly, “What I do with my own body is my business” — an uncommon proto-feminist pronouncement in 1970. The mix of far different types of dialogue not normally conjoined on the same soundtrack is part of a greater vision embraced by director Stephanie Rothman.

Sequences in this low-budget ($120,000) soft-core exploitation film, which she shot for legendary producer Roger Corman, are in large part a series of non-sequiturs. Barely related actions, sets, and language often abut with no pretense of smoothness. The slightly bumpy but oddly poetic narrative structure resembles the assemblage of concurrent scenes, one succeeding the other, in early silent movies, as well as in some much more recent avant-garde work that challenges codes of classical editing. Occasional dashes of comedy help ground kitschy exaggerations of character and plot.

The Student Nurses is high velocity. Its m.o. is acceleration, quite literally in the case of cars and bikes that rev up from start to finish. Rothman offers a sample of her style in the very first sequence. A manic patient tries to rape one of the women, then runs off to brutally assault a male doctor. Overall, editing is rapid, except between some badly dated slow-motion scenes comprised of subjective shots, like the hilarious ones from the POV of a gal on acid. The filmmaker’s agility with a moving camera comes in handy to maintain a dynamic feel. She often shoots a character from a variety of angles, not unlike in the paintings of some early modernists, to keep the kinetic sensibility constant.

Small crevices that puncture the film’s continuous motion open up a much more introverted space for the exploration of intimate thoughts and acts of the four feisty female leads, portrayed rather clumsily by Elaine Giffos, Karen Carlson, Brioni Farrell, and Barbara Leigh. They may share a flat and school, but they are individuated. In intercut sequences, each deals with her own sexual needs, as well as her own ethical positions.

The approach is rare for the era, when notoriously chauvinistic hippiedom was the predominant alternate subculture — which the film attests to with clothing that has not stood the test of time (bellbottoms and fringe, anyone?), folk tunes and mellow twangy guitar sounds then in vogue, and such period slang as — hold on — far out, groovy, and love in. Here we have a revisionist women’s picture that takes place in a specific time but turns out to be universal in its socio-political concerns — a far cry from the weepies that the studios had created as the domain for issues affecting the female population. The movie still startles 45 years after its premiere.

Corman had envisioned a mélange of cleavage and left-wing sympathies for the movies his newly launched New World Pictures would develop and distribute. Even though The Student Nurses was only his second film, it was a box-office hit. Rothman stuck to the chief’s formula, but managed to include her own progressive, largely feminist agenda as well.

We (Rothman, husband Charles S. Swartz, who shares a story credit with her, and screenwriter Don Spencer) were free to develop the story of the nurses as we wished, as long as there was enough nudity and violence distributed throughout it.…

For example, she unnecessarily but productively cuts away from the young women’s faces to their shapely legs. I’m not sure if the decision was based on generic necessity or simply the wish to insert a shot from the point of view of the ogling men surrounding them. There is no doubt, however, that a scene of two of the women taking off their blouses and exchanging them, for no apparent reason except to reveal their breasts, is a creative concession to the soft-core prerequisites.

Rothman continues:

This freedom, once I paid my debt to the requirements of the genre, allowed me to address what interested me: political and social conflicts, and the changes they produce. It allowed me to have a dramatized discussion about issues that were then being ignored in big-budget major studio films…It irritated me that many contemporary films…were dishonest about everything from sexual politics to social conflict. Since I didn’t know how long I would be able to work making any kind of film, I decided to say what I wanted while I had the chance…

Among the controversial topics she addresses are abortion, poverty, racism, and, of course, sexual politics, including two scenes suggesting lesbian proclivities (“Maybe I should try something else”). Half-naked men balance out the accepted double standard. Rothman claims she tried to dramatically justify female nudity.

One of the women, who at first divorces herself from those fighting to change the system, ends up joining a violent group of Latino activists — hardly the stuff of erotic movies. (The popular slur pigs for cops is uttered over and over again.) Another wants to terminate a pregnancy, at a time when abortion was illegal. The sequence depicting her solution is one of the film’s strongest, in spite of its awkward surrealist mood. Debatable questions pop up: Are illicit synthetic drugs dangerous? Are we the products of what we eat?

Rothman does not shy away from more intimate human struggles. Sex for her transcends pleasure, gratification, and exhibitionism, the mainstays of the genre is which she worked. Not merely a physical act, sex can be a gift, charity even: One nurse-to-be takes the plunge for a troubled young man with a death sentence looming. At the other extreme, sex can be a tool of revenge in this ultimately complex cinematic essay on a woman’s plight in an unfair social structure and her handling of possible options.

The Student Nurses is like a stand-alone building: Its kitschy, blue-film format is an isolated vehicle for timely, much-needed conversations about an assortment of subjects. The feature is in some ways a combination of four different shorts, each one about a female and the male-dominated society she contends with. They do share a characteristic way ahead of its time: None of them remains subordinate.

Sequels did not interest Rothman: Those ended up being directed by men. The film generated a genre of soft-core films centering on women working in a single profession. It also set the standard for a radically new kind of movie. She sums up its legacy:

The lesson Roger derived from my film’s success was that you could make exploitation films whose narratives included contentious social issues, including feminism, and he consequently encouraged his directors to do it.