Back to selection

Back to selection

Continue Watching

Exploring how and why we watch. by Jane Schoenbrun

A History of the Fan Mutation, YouTube’s Strangest Art Movement

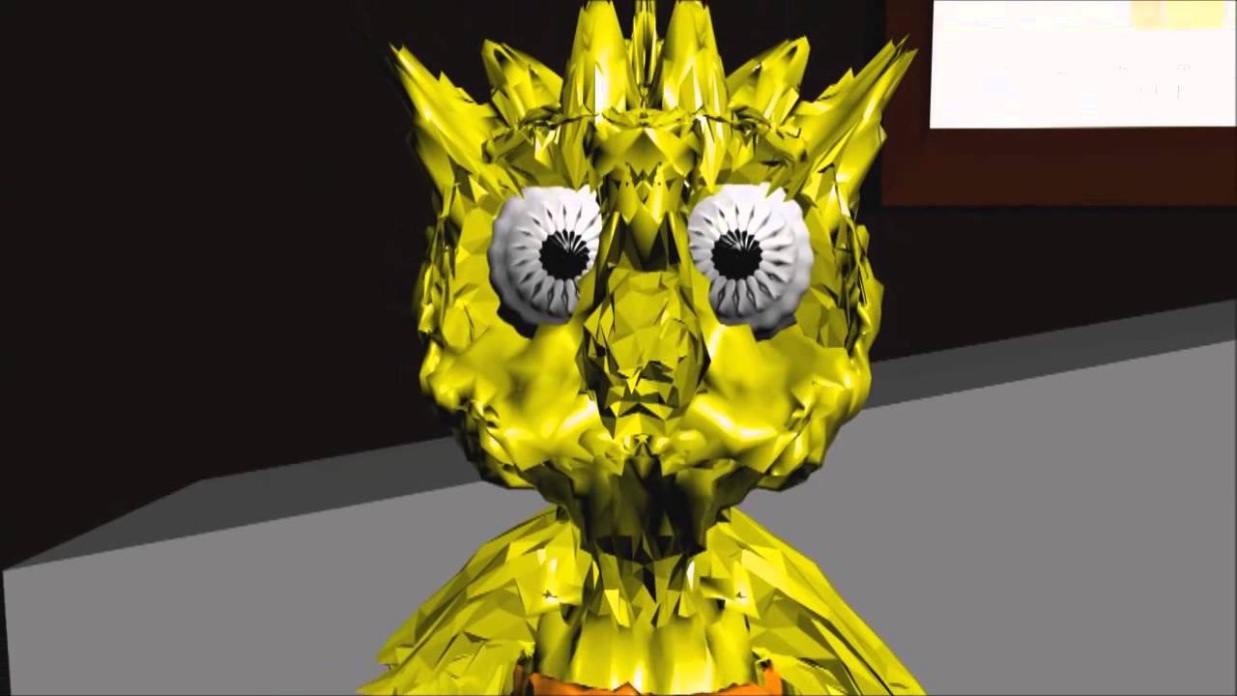

Andrew Wilson's Snopsis Eht

Andrew Wilson's Snopsis Eht There’s something comforting about TV show opening credit sequences. In the era of the binge watch, we don’t necessarily need them every single episode. (I mean, we all know what we’re about to watch, don’t we?) But a great credit sequence can serve as a palette cleanser. The cue that we’re about to see something familiar, something we trust. It’s almost Pavlovian.

And few opening credit sequences are as comforting as The Simpsons. Sure, that show, which is about to enter its 28th season, is about two decades past its prime. But when we hear Danny Elfman’s theme music, when we see that logo in the clouds above Springfield, it’s like we’re right back in 1995.

It’s this familiarity that French animator Yoann Hervo plays off of in his popular 2015 YouTube video Weird Simpsons VHS. Things start as a pretty much faithful recreation of The Simpsons’ credits, save some tracking lines and general wear meant to indicate that we’re watching the titular VHS tape. But as we travel through the letter “P” in “Simpsons” and down in the town of Springfield, it quickly becomes apparent that something is indeed very, very weird about this VHS.

Did we just see Comic Book Guy in his underwear, staring at Bart on his computer screen? And why is Bart banging his chalk violently against the blackboard instead of writing some joke on it? Whoa — did the grocery store cashier just swipe Maggie across the price-checker way too violently?

By the time Lisa’s classmates are replaced by a roomful of Lisa clones, all blowing off-key saxophone screeches in unison while the band teacher covers his ears and screams in pain, it’s pretty clear that what we’re watching isn’t The Simpsons proper. Rather, it’s a bad acid trip version of The Simpsons, recorded onto VHS in some alternate universe where Matt Groening’s creation looks a lot more like a David Cronenberg film.

Weird Simpsons VHS gains its power from distortion. It plays on our cultural understanding of the source material, our shorthand of what’s on and what’s off-limits in the reality of The Simpsons. From there, it provokes, disturbs and ultimately fascinates by bulldozing any and all boundaries.

Weird Simpsons VHS is the latest entry in an ongoing YouTube phenomenon that dates back over a decade. Videos in this movement work in a variety of mediums (animation, live action, computer rendering) to recontextualize specific pop culture properties of the recent past into distorted and often disturbing new forms. If nostalgia helps us remember the shows of our youth in a warm, glowing sheen, these videos are the opposite side of the coin. The cold, darkened nightmare.

The videos that make up this movement have garnered at least 50 million views on YouTube alone. And yet, there’s been little-to-no mainstream attention or discussion of the works as a whole. In fact, this genre of video doesn’t even have a name. Honestly, I’m not really sure what to call it.

“Remix art” (or, as it’s known somewhat less affectionately in the YouTube sphere, “YouTube Poop”) doesn’t really work, since the filmmakers in question are creating their own original content rather than repurposing existing media. “Fan film” or “fan fiction” doesn’t seem accurate, because the creators aren’t really paying tribute to the works they pull from. I suppose “parody” isn’t too far off, but even that feels insufficient. Most of these works seem totally disinterested in providing any meaningful commentary or critique of their source material.

“I personally don’t think of myself as a parody artist or a satirist,” Hutz, one prominent figure in the movement, and the creator of Hommer Simpson and Seinbluth, explained in an online interview.

“I’ve been making animations about things I remember on television from an early age because I like the subjectivity of memory and how people can have varying recollections of an event. Maybe I would just call it an alternate retelling, or an original story trying on the appearance of The Simpsons for size. I actually have not watched a lot of The Simpsons, and I have never seen Seinfeld. For this reason it’s hard for me to imagine this as ‘fan fiction,’ as I can’t confidently call myself a fan… I honestly didn’t know the names of the non-Jerry characters until I read about it online.”

For lack of an existing name to adequately describe this movement, this article will use the term “fan mutation” (similar to the term animutation, used to describe an 2001 online series of video remixes and re-appropriations by animator Neil Cicierega).

We’ll look into the history of this burgeoning genre. Its tropes and peculiarities. We’ll try to get a sense of its cultural significance.

To be clear, this isn’t a phenomenon that developed solely out of YouTube or even the internet. The idea that art can comment on art itself is at least as old as postmodernism. And the practice of utilizing and manipulating pop culture imagery into distorted new forms is pretty much the entire basis for Andy Warhol’s pop art movement.

More recently, plenty of video artists have riffed on pop culture in outsider, experimental work. Take David Lynch’s 2002 short Rabbits, for instance, which — though it’s not based on an existing property — shares many tropes with the videos that would later make up the fan mutation movement. And more recently, Spring Breakers jumps to mind, as no one familiar with Harmony Korine’s output would mistake his casting of Selena Gomez and Vanessa Hudgens as anything other than a darkened mutation of their existing pop culture personas. And then there’s Jon Rafman’s use of actual video game footage, or Ryan Trecartin’s sinister recontextualization of internet imagery and vernacular (which has been described by some as, “what it would look like if Facebook had a nightmare”).

But jump all the way back to 2001, back when the internet still mostly ran on dial-tone, and you’ll find the fledgling origins of the genre in Neil Cicierega’s “animutation” series. An assault of Flash animation and pop culture imagery set mostly to what sounds like Japanese carnival music, most animutations fall somewhere between Dadaism, remix art, and very early (like, prehistoric) meme culture. Cicierega, who was 14 when he started making and posting his animutations, followed the series with Potter Puppet Pals, an insanely popular and more straightforward satire of the Harry Potter series.

But the “fan mutation” as it exists today — in which specific pop culture properties serve as the basis for experimental new narrative storytelling — was really born out of YouTube. And indeed, what I would point to as the first entry in the genre proper was posted to YouTube in 2006, just one year into the platform’s lifecycle.

That video was a Simpsons riff as well (notice a pattern emerging?) created by an internet collective named Famicon and posted under the title, Bart the General. This first video, which shares a name with an actual Simpsons episode, was followed by three further installments. Altogether the piece totals over 40 minutes in length.

If you can get through it all, you’re a brave soul. Because Bart the General is not exactly The Great Train Robbery. In fact it plays somewhere between “I dare you to stop watching” performance art and a 12-year old’s film camp prank. The plot (if you could call it that) centers around a murderous Australian man named Toefish. The animation is so crude it makes South Park look like Van Gogh. Around the four-minute mark, Homer watches Toefish have sex with Marge on the living room couch while slowly screeching, “Marge, you are breaking my heart.” Later on, Dr. House, M.D. shows up.

But let’s put the video’s near unwatchability aside, because Bart the General is a fascinating specimen, primarily because of how it accurately presages (and arguably establishes) so many of the tropes that would come to define the fan mutation genre: intentionally shoddy animation, characters’ faces being rendered in misshapen, oddly detailed forms, names being intentionally mutated themselves (Homer is Omarn, Bart is Burton). One can trace many of these elements to preexisting influences (certainly there’s a debt to Cicierega’s animutations here, as well as cult hits like Ren & Stimpy and Salad Fingers). But the motifs established in Bart the General are recreated so specifically in future mutations that it’s hard to deny the piece’s influence. Something about this twisted little nugget struck a chord.

In fact, the video’s rise to prominence was an unusually engineered effort. It began in the Something Awful forums (an online community that has spawned many an internet phenomenon), when founder Richard “Lowtax” Kyanka issued a challenge to the forum: see if they could collectively make this seemingly incomprehensible video go viral.

“I was curious to see how difficult it would be to artificially manufacture a viral Internet fad,” Kyanka wrote in a post on August 5th, 2006. “I didn’t really have any target until I saw this video: This is one of those things so completely random and messed up that, I figure, it’d be the LEAST likely to ever turn into a meme or successful viral Internet fad.”

Ten years later, Bart the General has garnered over 700,000 views. As far as “successful viral Internet fads” go, that’s good but not great. But little did Kyanka know, “fad” wouldn’t even begin to describes the video’s influence and impact.

Two years later, the burgeoning fan mutation movement produced its first bonafide classic. Lasagna Cat.

The brainchild of then 25-year-old filmmakers Zachary Johnson and Jeffrey Max (founders of the production company Fatal Farm), Lasagna Cat applies the mutation treatment to, you guessed it, America’s favorite Monday-hating, morbidly obese cat. Across a total of 27 episodes all posted in 2008, Johnson and Max offer surrealist live action adaptations of actual Jim Davis Garfield strips. Tonally, the shorts are not dissimilar from that same year’s Garfield Minus Garfield, an absurdist online comic that removed Garfield from Davis’ strips, thus painting owner John as something of a delusional schizophrenic.

2008 truly was the golden age of experimental Garfield humor.

Lasagna Cat operates with a surreal emotional deadpan. While Davis’ comics might pass as witty on the page, when adapted to live action with a straight-face, a canned laugh-track and actual adults in lifesized Garfield and Otis costumes, the absurdity is absolutely potent. As a cherry on top, before the end, each episode dissolves from adaptation into some form of music video freakout, remixing what we’ve just watched into bizarre new form.

For instance, after a strip in which Jon chastises Garfield for lying to him, we’re treated to a slow-motion breakup video set to the chords of Spandau Ballet’s “True.” Images flash across the screen — a judge’s gavel, roses, large white text announcing, “Garfield is a liar.” In the original strip, Garfield is seen holding a teddy bear. In this music video remix, he slowly strokes the bear over and over again, as if he’s caught in some kind of Lynchian loop.

Johnson and Max explained the series’ origins in an email interview:

It evolved into something very different, but the Lasagna Cat series was originally inspired by Joe Mathlete’s “Marmaduke Explained” blog. We happened upon a ratty off-brand Garfield costume in a south central L.A. costume shop and decided that we’d create and maintain a blog featuring live action recreations of each day’s Garfield strip. We’d buy a daily newspaper, shoot the strip and post it by evening. We thought that’d be a fun thing for people to follow. But as we were practicing this routine, we realized how exhausting that’d be to keep up.

So then we decided we’d shoot 100 Days of Garfield as a concept series. So we chose a bunch of Garfield strips throughout the years and started shooting and compositing them. We got through close to 80. As we were watching them, we realized once you’d watched three or four, there was no motivation for a viewer to watch the fifth, sixth, etc. They were all the same. Which, obvious in retrospect, is the universal criticism of Garfield itself. So we thought, “What are we going to do with all these Garfield strips we shot?” We decided to cut our losses on the larger project and cut a montage out of all 80 strips set to a saccharine tribute song to Jim Davis. Seeing the live action strips set against music was really funny and we backed ourselves out of the 80 strip mashup into the 27 strip-music videos we eventually landed at.

The Daily Dot recently called Lasagna Cat “the first true masterpiece of weird YouTube.”

But this wasn’t Johnson and Max’s first mutation. They had previously created Alternate TV Intros, a series of mutated TV opening credits that works from a premise similar to Weird Simpsons VHS. In one entry, The Golden Girls are baked into cookie form and eaten by an anonymous overlord. In another entry, the Disney cartoon Ducktails is reimagined as a live action tale of online sexual predators wearing life-sized duck costumes.

“It felt like video sampling was just becoming a thing like audio sampling had been decades earlier,” the duo explained. “People had made fan films, but now people were starting to re-appropriate content for thematically unrelated purposes. Stuff like Neil Cicierega’s ‘animutations.’ That was interesting to us. To sample things ‘incorrectly’ and without motivation. ‘Why would someone do this?’ Or more specifically, ‘Why would someone do this so thoroughly and conscientiously?’ It’s so dumb.”

Lasagna Cat only ran for that initial run in 2008 before Johnson and Max moved on to other projects. Though in recent years, they’ve been hard at work on the long-awaited second season, which they promise will feature, “a stupefying volume of new and confusing graphic Garfield content.”

It took two years for Lasagna Cat’s closest torchbearer to emerge, 2010’s The Jerry Seinfeld Program.

A similarly-inspired exercise in anti-comedy, The Jerry Seinfeld Program was the brainchild of emerging UCB comedians Dan Klein and Arthur Meyer. In their mutation, Klein and Meyer play Jerry and George, respectively, performing the majority of the series’ 22 episodes in front of a green-screen version of the apartment from the actual Seinfeld. Their impressions are surprisingly good, but Meyer’s bald-cap only partially covers his full head of hair.

The content of The Jerry Seinfeld Program’s early episodes is purposefully bland and nonsensical. In the first installment, George spills a can of beans on himself, prompting him and Jerry to begin listing different types of beans to each other for the remainder of the episode. In another early installment, the two just agree and disagree with each other over and over again, intoning variations of “yes” and “no” back and forth as if participating in an acting exercise. It’s all performed with strict adherence to the real characters’ real inflections. Laugh track is haphazardly interspersed throughout. At the end of each episode, that iconic Seinfeld bass lick freeze-frames us into a listing of the NBC show’s executive producers.

As the series progresses, the content grows darker. One late episode entitled “Whores” finds Jerry and George delivering a string of profanity-laden, sexist slurs at a feverish pace (they apologize in the next episode). In the penultimate installment, Jerry flatlines in a hospital bed, puking up milk and convulsing. George screams at the top of his lungs and drinks rat poison. For the entirety of the final episode the two simply lay lifeless together in that same hospital bed. It’s silent until that familiar bass lick comes in, signalling the end of the series.

“I think we were both a little sick of trying to come up with clever sketches to try to make some kind of splash in the comedy scene,” Klein explained to The Daily Dot in 2013. “What would a delusional, psychopathic Jerry Seinfeld write about? That was a lot more fun than than just the idea of more episodes of Seinfeld.”

The creators of both The Jerry Seinfeld Program and Lasagna Cat would eventually go on to find success in the more mainstream comedy scene. Klein and Meyer went on to become writers and performers for The Onion, CollegeHumor and Late Night with Jimmy Fallon. And The Fatal Farm duo became prolific TV and music video directors.

“Luckily for us, each one of our fan projects has directly resulted in work,” they explained. “The ‘TV Intros’ put us on Lonely Island’s radar and won us the opportunity to help out on the MTV Movie Awards. Later, Lasagna Cat introduced us to Tim and Eric, and we got to shoot and edit a couple Major Lazer videos directed by Eric Wareheim. Most recently, our genital-centric Robocop film earned us the chance to direct a few episodes of the final season of Key and Peele.”

These early entries in the genre were the born from emerging professionals hoping to break into the mainstream comedy scene with edgy new works. But as the aughts wound down and YouTube began its meteoric rise to prominence, the fan mutation genre began to spawn more amateurish, more insane, and more frequent entries.

2009 brought Snospis Eht, another Simpsons mutation, this one from U.K.-based YouTube animator Andy Wilson.

One can draw a straight line from Bart the General to the lo-fi animated stylings and distancing tactics of Snospis Eht’s first installment. But from there, the show quickly evolves into a more interesting chaos: the Simpsons are rendered in grotesque and increasingly complex computer animation, their bodies misshapen like something Tim Burton might sculpt out of Play-Doh. Lisa is voiced by a computerized voice generator. The characters wander through an apocalyptic hellscape that resembles a Pixar adaptation of Eraserhead.

Wilson expanded on his style in an email interview:

I find that a dirty distressed look combined with similarly distressed audio gives my videos an otherworldly feel. My only real goal is to have the character be recognizable as the thing that I’m basing it off of. Beyond that there’s no plan. I just go with what feels right at the time, which is why everything looks a bit deformed. I’ll model something in 3D and have it come out odd looking. If I like the look of it, though, and feel it fits, i’ll just roll with it instead of fixing it.

2013 brought the burgeoning genre’s most extreme entry yet: the infamous Dilbert 3. From YouTube filmmaker “CBoyardee” (real name: Eric Schumaker), this version of Dilbert mutates the source material’s deadpan corporate malaise into a psychedelic, hyper-violent, drug-induced office shooting spree. It’s pitch black, disturbing stuff, almost begging you to question the mental state of its creator. But it’s also impressively off-kilter, a natural heightening of the groundwork established by the genre’s earlier entries, and the kind of cult artifact you used to be able to unearth hidden in the depths of Kim’s Underground Video.

Dilbert 3 quickly received over a million views on YouTube, making it, to that point, the genre’s most popular entry. During a 2013 Reddit AMA, a fan even shared Dilbert 3 with Scott Adams, creator of the actual Dilbert.

His response? “I find it disturbing that Dilbert’s shirt pocket is on the wrong side. Otherwise, art is art.”

But for those looking for the most concise example of the genre to date, well that would be 2013’s Jimmy Neutron Happy Family Happy Hour.

Based on Jimmy Neturon, Boy Genius — a lesser-known Nickelodeon computer animated show from the ’00s — Family Happy Hour subjects the Boy Genius to his mother’s murder, his father’s beheading, and a brutal attack from a sentient pizza pie (“the pizza is aggressive!”), all in the span of one minute and six seconds. Like past mutations, the dialogue is voiced by computerized voice generators, thus forcing the titular character to mispronounce his last name as “Nut-truhn.”

Most memorable though is Neutron’s face, which, once you’ve watched the video, you won’t be able to unsee. It’s rendered in disturbingly realistic computer animation, a harsh contrast to the rest of the short’s fly-by-night styling. Neutron looks older and basically nothing like the character he’s based on. That is, aside from his trademark red t-shirt, blue shorts, and impossible to mistake top-of-an-ice-cream-sundae hairdo.

If you’ve started to sense some repetition in these examples, that’s because by this point an established set of genre conventions has emerged: purposeful misspellings and anachronisms, fractured and unfinished animation, distorted vocal recordings, profane and taboo subject matters, the merging (and manipulation) of different pop culture universes into one, selective hyper-realistic, grotesque imagery.

In 2016, these conventions are well established and YouTube’s library of mutations quite extensive. If you’re a fan of a beloved pop culture property of the recent past, chances are there’s a mutation for you. There’s Sonic the Hedgehog, Thomas the Tank Engine, Rocko’s Modern Life. There are mutations of Scooby Doo and Pokemon, in Spanish no less. There are countless additional Simpsons and Garfield spins beyond the ones discussed in this article. There’s Scrooge McDuck. There’s the Pringles guy. And then there’s Shrek.

Oh lord, is there Shrek.

No overview of the “fan mutation” movement would be complete without discussing Mike Myers’ lovable green ogre. Shrek has become an absolute staple of the genre, so much so that one YouTube user has started an annual tradition of collecting the year’s best Shrek mutations into compilations (it’s been going for four years now). In an ironic spin on the My Little Pony subculture of “bronies,” the Shrek “fan” community call themselves “brogres.”

How did this begin?

Coincidentally (or maybe not), this subculture has its roots in a diary video by Eric Shumaker, creator of Dilbert 3. Entitled “Shrek is NOT Dreck!,” the video finds Shumaker spewing vitriol at all those who would seek to hate on the Shrek franchise. That video helped spawn the “brogre” subculture, which in turn spawned a meme known as “Shrek is Love, Shrek is Life.’ in which Brogres recount sexually graphic first-person encounters with their jolly green giant idol.

The most famous “Shrek is Love, Shrek is Life” story begins:

I was only 9 years old

I loved shrek so much, I had all the merchandise and movies

I pray to shrek every night before bed, thanking him for the life I’ve been given

“Shrek is love” I say. “Shrek is life.”

My dad hears and he calls me a faggot.

Later, Shrek arrives in the boy’s bedroom:

He whispers in to ear, “this is my swamp”

He grabs me with his powerful ogre hands and puts me on my hands and knees

I’m ready

I spread my ass cheeks for Shrek

He penetrates my butthole

It hurts so much but I do it for Shrek

This story, first posted to online community 4Chan in 2013, was soon adapted into multiple audio recordings and then videos. By March 2014, a computer-animated adaptation of the story had been uploaded to YouTube. It’s been viewed ten million times.

In my humble opinion, this is a great short film. It would fit right in on the Sundance shorts lineup. And yet, the name and identity of the filmmaker is completely unknown. All we have to go on is a YouTube username: MrSykotiic. The writer of the original story also remains a mystery. He or she is credited in the original 4Chan post simply as, “Anonymous.”

It’s important to note that, as the genesis of “Shrek is Love, Shrek is Life” indicates, the internet’s obsession with mutating and recontextualizing pop culture is far from limited to the video format. Dig around the weirder side of the internet and you’ll find a popular Seinfeld Twitter account (@Seinfeld2000) that adheres to the many absurdist tropes established by these video mutations. Or several recent Clickhole pieces (including “How Many Of These Hayao Miyazaki Films Have You Seen?”; “You’re At Dinner With Your Friends Don Draper And Roger Sterling. Can You Eat The Most Oysters?”; and, “This Was Almost the Intro for The Sopranos“) pulled from the same tradition. There’s even an entire music genre called Simpsonswave (for more, I’ll direct you to Pitchfork’s astutely titled “What the Hell is Simpsonswave?”).

And then there’s Sonic.exe, a fully playable video game that starts as a faithful recreation of the 1991 Sega Genesis classic but then mutates into a hellish landscape replete with intentional controller glitches and legitimately frightening flashes of a red-eyed Sonic declaring himself a God.

Sonic.exe began as a creepypasta. If you’re not familiar with that term, I’d encourage you to carve out the better part of your day and just start googling. But, briefly, a creepypasta is the internet’s version of an urban legend (the name derives from “copy-paste”). Creepypastas are agreed upon fictions, but for all involved in their creation and propagation, they’re discussed as facts. Each story is a first-person account of an unexplainable, supernatural, or disturbing incident. Creepypastas are often developed by multiple authors, and accompanied by fan art, manipulated photos, or amateur video adaptations.

Creepypastas are also ridiculously, ridiculously popular.

And several of the most famous ones fit squarely within the “fan mutation” genre. These stories don’t necessarily put their narrators in any imminent danger, but instead simply recount the details of a creepy, “lost” pop culture artifact. For instance, in the creepypasta “Dead Bart,” the author meets Matt Groening at a fan convention and is given a link to a secret Simpsons episode in which Bart is sucked out the window of an airplane. We then bear witness to a long description — and accompanying photo — of Bart’s battered corpse. In the creepypasta “Squidward’s Suicide,” by creepypaste, a group of Nickelodeon PAs are accidently made privy to a previously unseen Spongebob episode, which ultimately reveals itself to be something closer to a snuff film. And in “BEN Drowned,” the author buys a used Zelda cartridge and discovers that it’s haunted (and thus mutated) by a previous owner’s ghost.

Each of these stories has spawned numerous video adaptations on YouTube (or in the case of “BEN Drowned,” a playable game, which then spawned numerous gameplay videos). If you go digging through the YouTube heap you’ll even find a seven-minute animated rap battle with over a million views in which “Dead Bart” faces off against “Squidward’s Suicide.” To clarify, that’s not a rap battle between the characters of Bart and Squidward. Rather, it’s a rap battle between the creepypasta stories. At one point “Squidward’s Suicide” taunts “Dead Bart” with the line, “drawing hyper-realistic looks fucking lame.”

Andy Wilson, the animator behind the Snopsis series, has adapted many creepypasta stories into videos on his YouTube channel. These usually come at the request of his YouTube followers.

“I don’t normally take suggestions,” he explains. “But creepypastas tend to work well with my style. Again, it lets me subvert everyone’s expectations. If someone’s familiar with the creepypasta they might be expecting a straightforward adaption. So it’s a lot of fun to change things around and make the characters act in an unusual way. My Sonic.exe adaption, for example, completely avoided the plot of the original and went in its own direction, essentially creating its own narrative.”

True to form, Wilson’s has mutated a mutation.

It’s easy to condescend when discussing this young but by-no-means-nascent genre. Once you’re through YouTube’s algorithmic canon and on to the genre’s deep cuts, it can at times feel like the vast majority of the genre is dominated by deranged juveniles testing just how offensive, shocking and annoying they can be.

Indeed, many of the lesser-seen videos are shock for shock’s sake, or worse, a halfhearted excuse for an onslaught of sexism, racism and other hate-speech.

Perhaps it’s this reputation that causes many of the movement’s leaders to remain anonymous. That’s not true for everyone — Wilson, for instance, makes no effort to hide his online work from friends, family or even co-workers at his day job. But many artists working in the medium keep their identities purposefully obscured or hidden behind YouTube aliases. Can you really blame people for not wanting their names associated with erotic Shrek adaptations, especially if there’s even a remote possibility at some point in the future that they’ll be going on a job interview?

When confronted with the many mysteries of the genre, one’s instinct is to become an amatuer private investigator and try to track down the mysterious auteurs behind these videos. And you wouldn’t be alone. There’s even an entire subreddit dedicated to uncovering the identity of seinfeldspitstain, the filmmaker behind Jimmy Neutron Happy Family Happy Hour. On YouTube, seinfeldspitstain lists himself (or herself) simply as “Bryan Smitthee.” It takes several Reddit posts calling for background checks before someone points out that “Smithee” is in fact a common pseudonym.

And then there’s RabbitohFans123, the YouTuber who posts the series Hommer Simpson. He claims to be doing so on behalf of a mysterious friend named “Hutz” who supplies him with videos through email and CD-R. There’s a fair deal of Internet speculation that RabbitohFans123 and Hutz are in fact one and the same.

“I’m not anonymous in the sense of obfuscating an IP address or anything,” Hutz explained to me via a Facebook message passed on by his proxy. “The only reason I have communicated/released projects through friends like RabbitohsFan123 is because I miss the time where there was little pressure to tie an IRL identity to an internet handle. ‘Anonymity’ as far as using a handle and releasing things sparingly puts me in a comfortable headspace to work, and I don’t have to worry so much about what people might think.”

In other cases, filmmakers working in the genre have been known to disavow entire catalogs at a moment’s notice. In 2013, Eric Shumaker (AKA CBoyardee), the creator of Dilbert 3, made his YouTube account private. In 2014, he deleted it entirely, though most of his videos have since been reuploaded by fans. Shumaker continues to maintain an online presence, but has given no explanation for his account deletion. He did not respond to a request for interview.

The deeper one digs, the question becomes: Is it really time for a critical evaluation of this genre, even when many of its most prominent creators don’t want to take credit for their work? And the answer is yes. Absolutely.

Because like it or not, the “fan mutation” has struck a chord. Consider the fact that Jimmy Neutron Happy Family Happy Hour has been watched over eight million times. For the sake of context, that’s thirteen times as many views as The White House’s official upload of the 2016 State of the Union.

You can argue that videos in this genre haven’t come close to any sort of creative peak. You can argue that videos in this genre might not even be legal (hey, IP lawyers: what’s up with that?). But it’s hard to argue with the fact that these videos have become a significant part of our cultural zeitgeist.

And that’s not just because they’re insanely popular. No — these videos speak directly and uniquely to one of the chief concerns of art in the internet age: the fractured notion of authorship.

Each fan mutation carries with it an inherent acknowledgement that our art and entertainment is no longer broadcast down a one-way street. Instead, these videos argue, the media we consume exists as part of an increasingly complex, interconnected system. First, the mainstream media broadcasts a signal outwards. From there, our twisted human antennas (or, as scientists might call them, brains) pick up the signal, convert it into something new, and broadcast it back out.

This conversion and rebroadcast used to happen in private — in our dreams at night and in the way that pop culture silently informs and influences pretty much all of our societal norms. But with the internet’s democratization of production and distribution, not to mention the added bonus of convenient anonymity, we can now share our rebroadcasts — our mutations — publicly.

Put another way: if our brains consume media the way our bodies consume food, this might be what lies on the other end of that digestive process. The waste we defecate back out.

A new art form.