Back to selection

Back to selection

True Crit

Weekly film reviews. by Howard Feinstein

Disbelief: Federico Veiroj’s The Apostate

The Apostate

The Apostate Barring lapse or conversion, how do you spurn religion? For centuries, Catholics have had a formal means to renounce the Church: apostasy. The tedious process, sometimes ritualized with a walk backwards from the altar to the front entrance, aims to remove all official documents pertaining to one’s baptism. Upon entering adulthood, some practicing laypeople begin to see it as involuntary. They want to own it by revising the past, in spite of the fact that, according to Revelations, a stigma accompanies disavowal: an indelible stain of apostasy, aka the mark of the beast.

A de-baptism movement has been under way in several countries, including Spain, the setting for Uruguayan director Federico Veiroj’s magical The Apostate, a balancing act between not only heady and humorous but also sacred and profane. But…Rome, we’ve got a problem. Among purist clergy, baptism and relevant records are thought to be inviolable. Not so, for repudiators: The rite is meaningless, the documents a mere database.

How do you battle intractable dogma? Skirt it? Not in The Apostate. Its co-writers are the increasingly surprising Veiroj, a Sephardic Jew who lived for some time in Spain, and a close friend, Spanish non-professional Alvaro Ogalla. The latter, who portrays smart, laid-back protagonist Gonzalo “Gonza” Tamayo, had personal experience with apostasy; the former, as we will see, makes movies addressing secular variations on this form of resistance. For a film that challenges the notion that all things baptismal are unassailable, their solution, perhaps surprisingly, is for their apostate to follow to the letter the Church’s proscribed protocol for disassociation.

The irony of Tamayo’s strict adherence to ancient procedure is that, as his mother perceptively claims, it is just a whim. He is such a rebel without a cause that he grabs onto this one, maybe because instructions are so precise that he needn’t expend additional energy necessary for an anti-commitment with more elastic rules for quitting. Structure is at the service of the unstructured. But is there a less severe path toward apostasy?

The mission, which is for Tamayo black-or-white, ultimately becomes clarification hell. He is convinced that he is persecuted by the non-consensual relationship. Paranoia infuses his fantasies, which are more nightmare than dream. His approach to a social role which he feels constrains him expresses a more expansive desire for freedom. He is, after all, stuck in youth. Memories of adolescence surface; they coexist with the present reality of this lost, unemployed, failing student. He holds on tightly to an earlier phase that threatens to bud into a grown-up sensibility. From the dissonance emerges the film’s edgy dramatic tension.

Though only half-evolved in some ways, Tamayo is complicated. He had been pampered as a child. Boredom was, and remains, his principal problem. In his youth, he bullied; we see it in flashbacks. In the present, he can not bear the bit of work he somehow manages to perform: filling out and delivering mundane but cryptic invoices for his father—himself rather cryptic. Apostasy fills the void.

He fears losing the small pleasures of pre-adulthood, like flirting and seeking sex woman to woman. Bizarrely, and possibly lacking credulity for some, he possesses a superiority complex. A professor accuses him of hubris, qualifying that it is grounded in ignorance. This is not the sort infecting arguable intellectuals like Dostoevski’s Raskolnikov or the gay couple in Hitchcock’s Rope, no matter how twisted the manifestations. Is Alvaro smart or stupid? Maybe both.

What could guide him into a more mature passage is the potential dormant in a new dual relationship: with his cute neighbor, Antonio (Kaiet Rodriguez), a bright, curious boy whom he tutors, and the child’s beautiful single mother, kind, level-headed Maite (Barbara Lennie). Involvement in Antonio’s life could pull him from the quagmire. Progress is possible should he become more healthily intimate with the mom. He might even abandon his established retrograde pattern on the female front. Come on, she’s gorgeous, but messing around with married first cousin Pilar (Marta Larralde)?

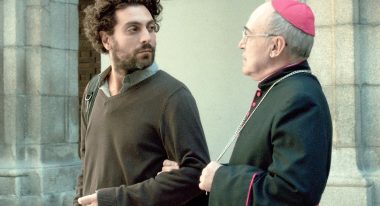

Tamayo is lost on both spiritual and intellectual planes. Recurring theological discussions with Bishop Jorge (Juan Calot), liaison for his apostasy, and lesser sparring about secular issues with the professor carry equal weight. Veiroj undercuts it all democratically, accompanying the verbiage with over-the-top, hilariously vulgar scenes of reverie. Tamayo walks into an orgy of nude couples, males erect, many engaged in coitus. In an absurd sequence on a bus, an older woman in the next seat clandestinely rubs his hand, then slides hers down to his bulge; following this foreplay, he reciprocates, his lips to her breast in full view of the other passengers. On the soundtrack, the bishop spouts so-called words of wisdom overused in ecumenical circles. Quoting St. Ignatius and St. Augustine, he casts these heretofore sacrosanct holy men in a new light.

This is all dryly amusing, but not belly-laugh funny like the incongruities of cloaked nuns lined up working their desktops. The co-writers do not want the arguments to be taken too seriously. They needn’t worry. In order to avoid the consistency that would require, Veiroj milks counterpoint throughout the narrative, and, especially and exceptionally, on a fine eclectic score that includes Prokofiev, revised music from the Spanish NoDo newsreels and docs from the period 1943-1981, Flamenco guitar and song, and Basque post-punk from the group Lisabo. Postmodernism for the gifted.

Inconsistency, however, does not mean discontinuity. The glue that holds the film together is Tamayo’s voice-over from beginning to end, a model of narrative doubling that objectifies. He reads aloud from a letter he has written to a childhood friend. Even though the starting point of the project was an actual collection of Alvaro’s correspondence, the danger of cheesiness lurks in this method of connecting the dots in a film blurring fantasy and reality. But it works almost seamlessly, visuals often linked by graceful sound bridges.

Mobility within stasis propels the narrative, even in scenes not absolutely required for the plot (one in a café with a Flamenco guitarist, for example), but which enrich it with texture. Veiroj does not push action per se. As in his earlier work, he is more interested in placement of characters in spaces and structures where they function–and occasionally don’t.

Apostasy is broader than matters of the spirit. In one of the multiple fantasy sequences, a group of men become collective apostates, rebelling against both the Church and a tyrannical secular state. Veiroj’s films observe entrapment in assorted metaphoric prisons, their protagonists refuting being defined by either an institution or a set of beliefs. They are all apostates.

The most personal of these are the rites in Acne (2008), about coming-of-age among Jewish teens in Montevideo; and a world limited by the sole vantage point of cinema in A Useful Life (2010), drawn from his own experience as a programmer in that city’s cinematheque, and featuring Jorge Jellinek, its most recent head honcho. The Apostate may be Catholo-centric, but Tamayo is besieged within a milieu of discourse close to the filmmaker’s own cerebral makeup.

Apostasy suggests melancholy. Besides ingenuous, no-frills execution, sly, surreal, and perverse comedy—among the cinematic influences cited by Veiroj are Marco Ferreri’s The Audience, Welles’s The Trial, and the gestures of Fernando Rey in the early films of Bunuel–lifts The Apostate out of a dark place into a joyful light. Informed optimism? Quizas.