Back to selection

Back to selection

Stage Fright, Escape from L.A. and Marc Allégret Films on OVID: Jim Hemphill’s Home Video Recommendations

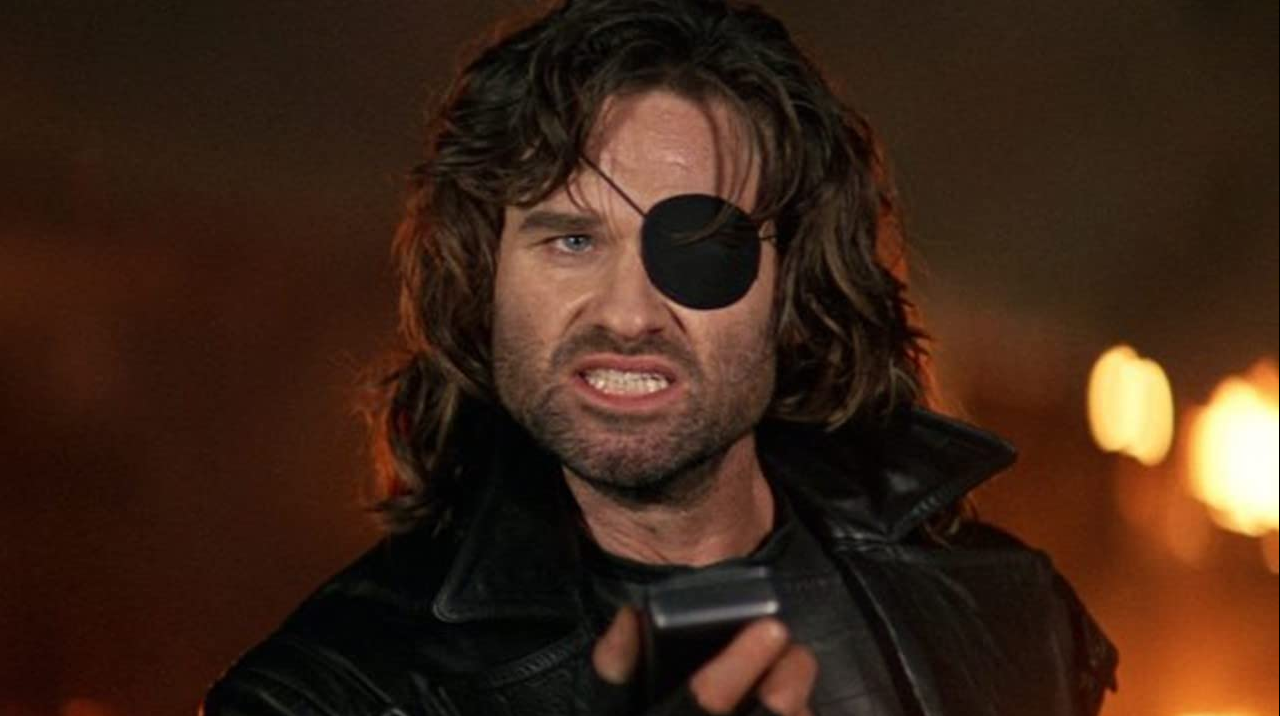

Escape from L.A.

Escape from L.A. From its opening shot of a curtain rising on a London cityscape to its climactic revelation that an earlier flashback sequence was a lie, Stage Fright (1950) is one of director Alfred Hitchcock’s most intriguing and playful investigations into the cinema’s power to deceive and manipulate. After Stage Fright received mixed reviews and collected lackluster returns at the box office, Hitchcock regretted tricking the audience with the unreliable narrator of the film’s controversial flashback, but I think the bold audacity of that device is actually one of the greatest strengths of a movie that has many, from the cleverly designed breakaway sets that facilitate elaborately choreographed camera moves to a script (by Whitfield Cook, James Bridie, and Hitchcock’s wife Alma Reville) that constantly shifts point of view between often dishonest characters, creating a more sophisticated and unpredictable form of audience identification than one usually finds in Hollywood studio pictures of the era. Although the setting – the London theater scene, where a drama student (Jane Wyman) tries to solve a murder of which her crush (Richard Todd) has been accused – introduces a sense of artifice into virtually every scene, Stage Fright is filled with subtle observations about behavior and psychology that anticipate the string of Hitchcock masterpieces (Rear Window, Vertigo, Psycho) that were just around the corner; it’s as wildly stylized on the surface as it is insightful and realistic in its characterizations and motivations. Ultimately the whole thing is a kind of inquiry into how and why art lies, and whether or not those lies lead to greater truths; the answers remain tantalizingly out of reach at the movie’s conclusion, but the questions make Stage Fright a fascinating final film in the experimental phase of Hitchcock’s post-David O. Selznick career that also included Rope and Under Capricorn. Stage Fright is newly available on Blu-ray from Warner Archive, with a terrific accompanying featurette that contains analysis by Peter Bogdanovich, Richard Schickel, Robert Osborne, and other erudite Hitchcock scholars.

One of Hitchcock’s most accomplished and intelligent disciples, John Carpenter, also has a new disc on the street this month in the form of Paramount’s 4K reissue of Escape From L.A. Released in 1996, the sequel (to 1981’s Escape From New York) is both a throwback to the sharp, unpretentious genre flicks of Carpenter’s early glory days and the crowning achievement of his late period foray into sociopolitical apocalypse movies (Prince of Darkness, They Live, In the Mouth of Madness). These angry, funny, and terrifying depictions of the end of the world were great when they came out, and they play even better now – the ferocity of Carpenter’s cynicism has largely been validated by recent global history, and the elegance of his visual classicism is more pleasurable than ever given how rare it has become. Escape From L.A. is as grim a film as Carpenter ever made – the hero essentially wipes out centuries of history and progress with the push of a button, and that’s presented as a “happy” ending – but it’s also one of his most beautiful, with stunning production design by Blade Runner’s Lawrence G. Paull that integrates gorgeous matte work and miniatures with then relatively new digital effects technology. The end result might look too fake for literal-minded viewers, but it has a lovely handmade quality characterized by distinctive personal touches and imaginative reinventions of Hollywood landmarks. Although the budget was reportedly the highest of Carpenter’s career (somewhere around $50 million), his approach isn’t that different from that of his more modest productions; aside from leading man Kurt Russell (who was riding high in the mid-90s thanks to the success of movies like Executive Decision and Stargate), there are no showy names – just a parade of great character actors (Steve Buscemi, Peter Jason, Robert Carradine) and stars of earlier eras (Pam Grier, Cliff Robertson, Peter Fonda). They’re all extremely game for the pulpy excesses of Carpenter, Russell, and Debra Hill’s script, and their exuberance – along with Carpenter’s typically expressive use of the Panavision frame – makes Escape From L.A. a gleefully entertaining argument for why we are all doomed.

A lighter, more romantic form of gleeful entertainment can be found in a trio of underseen French classics currently streaming on the OVID platform: Julietta, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, and School for Love. All three are mid-1950s gems from Marc Allégret, a French writer-director who began his career with documentaries in the 1920s and early ’30s but ultimately moved into the more sensual style of filmmaking on full display in these later works. One of Allégret’s greatest strengths – and one of his most lasting contributions to film history – was his unerring instinct for how to best showcase performers via meticulous framing and lighting; he was instrumental in building the careers of numerous international movie stars, including Jeanne Moreau (featured in Julietta as the frustrated fiancée of a young lawyer with a wandering eye), Danielle Darrieux (Lady Chatterly in Allégret’s D.H. Lawrence adaptation), and Brigitte Bardot (one member of a romantic triangle between two female students and their married singing teacher in School For Love). Jean-Paul Belmondo and Louis Jordan’s careers got boosts from Allégret’s visual amplification of their star quality as well, and he gave Roger Vadim his start as an assistant director and screenwriter; Vadim co-wrote School for Love, which ended up being the first in a series of collaborations between Vadim and his future wife Bardot. It happened to be the least commercially successful (Vadim, Allégret, and Bardot would do much better financially with the following year’s Plucking the Daisy, leading to the 1956 juggernaut that was …and God Created Woman), but School for Love is a graceful and absorbing melodrama exhibiting Vadim and Bardot at the beginning of their rising artistic powers and Allégret at the peak of his. All of the Marc Allégret pictures have been lovingly restored and are streaming for the first time on OVID, which is also presenting a pair of restored works by another French master, Cahiers du Cinéma co-founder Jacques Doniol-Valcroze. His A Game for Six Lovers (1960) and The Immoral Moment (1961) have long been inaccessible, making all five of OVID’s exclusive presentations essential streaming appointments this month.

Jim Hemphill is a filmmaker and film historian based in Los Angeles. His website is www.jimhemphillfilms.com.